Stuart K. Hayashi

O Lord, I know that the way of man is not in himself: it is not in a man that walketh to direct his own steps.

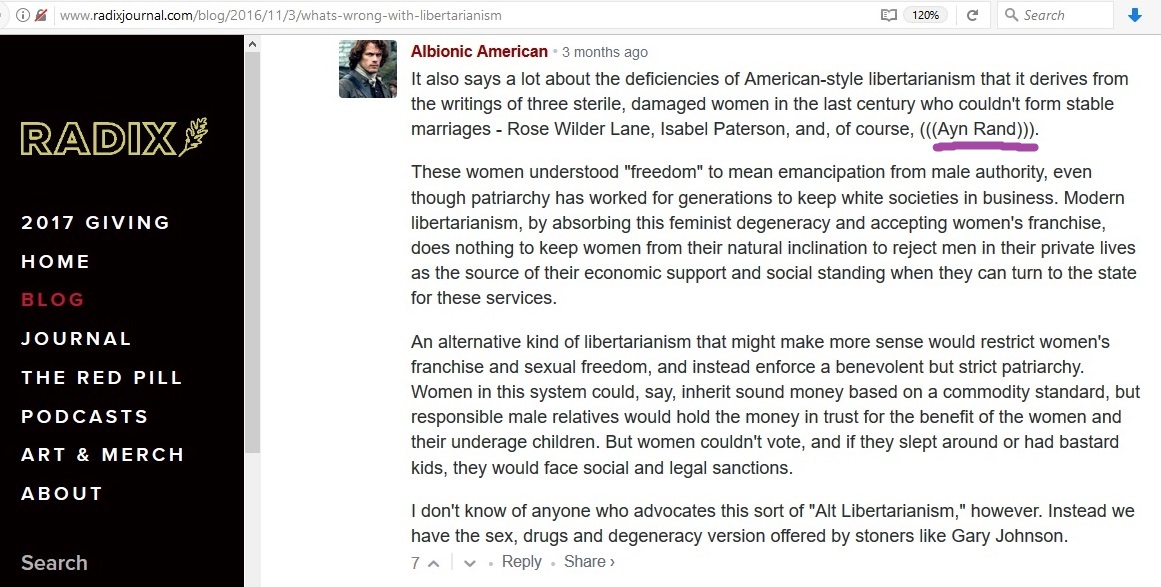

|

| Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. |

Popular atheist author and neuroscientist Sam Harris denies human volition. As he states in his short treatise Free Will,

Free will is actually more than an illusion (or less). Either [a.] our wills are determined by prior causes and we are not responsible for them, or [b.] they are the product of chance, and we are not responsible for them.

No, Spinoza and Harris, the Law of Causality Does Not Preclude Free Will

That first possibility that Sam Harris raises is actually an argument made by Benedict Spinoza. Spinoza was an excellent philosopher in many respects, but not in this one. This is the ar4gument. It is that to agree that the Law of Causality has both of the following implications.

- Every action by non-sapient objects was the logical consequence of some prior cause.

- We have the Law of Identity. The Law of Identity is that entities act only in accordance with their nature. Taking the Law of Identity into account, a specific action by a specific non-sapient object could not have been anything other than what it was. This is due to the nature of the non-sapient object and the nature of the prior event that stimulated this action.

Here is an example. On account of the levels of moisture in the air, a lightning storm occurs. A bolt of lightning strikes a branch of the tallest tree in the nearby forest. The lighting strike severs the end of the branch from the rest of the tree. The rest of the tree catches fire. All of the actions pertaining to the tree could not have occurred in any manner other than they did.

It is not as if the lightning strike could have magically transformed the tree into a giant dove and made the dove-tree fly into space. No, if a bolt of lightning strikes the tree (Event A), the tree will catch fire and the branch that was struck will be damaged (Event B). On account of the respective natures of the objects in question — the nature of trees, lightning bolts, and air — nothing but Event B could have resulted from Event A. That is the Law of Causality, also known as the Law of Cause-and-Effect. And the Law of Causality is the Law of Identity as applied to action.

As Spinoza would have it,

...nature is always the same... ...that is, nature’s laws and ordinances, whereby all things come to pass and change, from one form to another, are everywhere and always the same; so that there should be one and the same method of understanding the nature of all things whatsoever, namely, through nature's universal laws and rules. Thus the [human] passions of hatred, anger, envy, and so on, considered in themselves, follow from this same [metaphysical] necessity [meaning the same mechanistic determinism of cause-and-effect] and efficacy of nature; they answer to certain definite causes, through which they are understood... I shall, therefore,...consider human actions and desires in exactly the same manner...as though I were concerned with lines, planes, and solids.The argument of Spinoza — and, here, Sam Harris — is that if we accept the Law of Causality as valid, then that precludes human beings from having free will. The reason they say this is that surely human beings are physical objects, and the very same laws of physics and causality that apply to trees and air molecules and lightning bolts apply to human beings as well.

This is the idea. I am just as much a physical entity as a tree is. Therefore, any time some stimulus stimulates some reaction from me, that reaction was not my choice. No, the reaction was simply me (an object) responding accordingly. That is given the respective natures of both the stimulus and me as objects, No other outcome could have resulted.

If some random stranger comes out of a crowd and kisses me, for instance, and then I kiss back, as opposed to pushing the stranger away, then it means that I had no choice in the matter. I could not have chosen to push the stranger away. Rather, if I kiss back, that was the only possible outcome of the stimulating event. To deny that, presume Spinoza and Sam Harris, is to deny the Law of Causality and the Law of Identity.

Actually, another neuroscientist presents another option. This is Michael S. Gazzaniga of U.C. Santa Barbara in his book Who's in Charge? Gazzaniga points out that the Laws of Identity and Causality do not preclude unprecedented events from occurring (page 71). For example, at one point in the past, the universe was in one form — something dense and hot. Then the Big Bang happened, and the universe, as we know it, underwent what is metaphorically called an “expansion.” That brought the universe into the form with which we are more familiar.

Likewise, at one point in the past there were no life forms on Earth. Then some chemical reaction occurred, and the first singe-celled organism came to be. That first single-celled organism did not consist of any new matter that had not already existed on Earth minutes earlier. The matter constituting the first organism already existed prior to the first organism existing. Rather, what happened was that some rearrangement of matter, which had already been on Earth minutes earlier, brought about an unprecedented phenomenon. That phenomenon was the arrangement of constituent parts acting as an organism.

That new phenomenon is called an Emergent Property. First you start with a set of components. In most arrangements, those components do nothing new. When those particular components find a particular new arrangement, however, a previously unprecedented phenomenon occurs despite no new components themselves being added. That is the “emergent property.”

Gazzaniga argues that volition in organisms is similarly an emergent property. At one point in history, our ancestors were much like worms. Our worms ancestors did what their genes programmed them to do. However, over the course of millions of years of evolution and reproduction and mutation, the chemicals in the bodies of some ancestor of ours were arranged in a new fashion. That brought forth an unprecedented phenomenon. It was a new level of spontaneity in the behavior of this ancestor. It was an enlarged ability of this ancestor to act upon a wide variety of different behavioral options at its disposal. We had some rat-like ancestor whose abilities were closer to volition than that of its own worm-like ancestor. Then we had some ape-like ancestor whose abilities were closer to volition than those of the rat-like ancestor.

Recognizing that, over the course of billions of years, some unprecedented phenomenon can occur does not contradict the Law of Identity or the Law of Causality. The reason is that the Law of Identity is contextual. For instance, suppose I hold one American football and you hold another American football. Mine has a smudge on it and yours does not. I say they are both footballs. They have the same shape and are used for the same purpose. Therefore these footballs are both of the same type, the same identity. Because they are of the same identity, the same Newtonian laws should apply to them. If I release my grip on the football I hold, it will fall. The same should happen to your football if you release your grip on yours. In that respect, they are of the same identity.

However, that does not mean that both American footballs are exactly the same on the noumenal level. My football has a smudge, and yours does not. Mine was made in California; yours was made in New York. When I said earlier that both footballs had the same identity, I mean that they were same as far as we needed to be concerned in our present germane context. If we just want to play football or throw it around or experiment on Newtonian mechanics, the two footballs are similar enough to be considered of the same type and identity. It does not mean that the two footballs are exactly the same on the noumenal level.

The same applies to the emergence of living matter from what was once wholly nonliving matter. The laws of physics mean that, as far as we need to be concerned in most contexts in our lives, the same principles will apply consistently. Most objects that are released from our grip will fall to the Earth. In our normal dealings, physical laws are consistent. They are absolute within the context of our normal dealings. But recognizing this principle — the Laws of Identity and Causality — as contextual absolutes does not preclude the recognition that, because not all similar-and-like events are exactly the same at the noumenal level, it is the case that, once in a while, something unprecedented can happen.

The same applies to the emergence of living matter from what was once wholly nonliving matter. The laws of physics mean that, as far as we need to be concerned in most contexts in our lives, the same principles will apply consistently. Most objects that are released from our grip will fall to the Earth. In our normal dealings, physical laws are consistent. They are absolute within the context of our normal dealings. But recognizing this principle — the Laws of Identity and Causality — as contextual absolutes does not preclude the recognition that, because not all similar-and-like events are exactly the same at the noumenal level, it is the case that, once in a while, something unprecedented can happen.

In our normal everyday dealings, we can consider two reactions by the same sets of chemicals to be similar enough for us to classify them as being of the same type. Over the course of billions of years, though, because no two reactions are exactly the same at the noumenal level, something unprecedented can happen. Hence, living matter arising on Earth when, just minutes earlier, all matter on Earth was nonliving.

Do Benjamin Libet, Chun Siong Soon, and John-Dylan Haynes Disprove Free Will?

In Libet’s original career-making experiment, conducted in 1979, Libet hooked the human test subject up to an electroencephalograph (EEG), which measures brain activity. In this particular experiment, the EEG measured brain waves in the part of the cerebral cortex most strongly associated with one’s readiness to make motor movements with one’s own body. When someone is ready to move a specific muscle, but has not yet moved, the EEG indicates the activation of one’s “readiness potential.” That refers to the readiness to initiate motor movement.

Similarly, the first organisms were relatively predictable in their behaviors, as worms seem predictable to us, doing what they were programmed by their genes to do. But among the myriad random mutations in the history of our ancestral germline were mutations that made our ancestors, over the course of several generations, more spontaneous and volitional.

If the Law of Causality were some Platonic Imperative that transcends all context, then Spinoza and Sam Harris would be correct (1) that it precludes volition and (2) that it even precludes any unprecedented event from occurring ever. However, we can instead recognize the Law of Causality as a contextual absolute. That means that the Law of Causality regularly applies within the context of our normal everyday dealings, but that, over the course of billions or trillions of years, it does not mean that all natural events of a similar type will be exactly the same at the noumenal level. Depending on how granular we want to be in examining similar events, there may be minute differences. If we recognize the Law of Causality that applies consistently in the pertinent contexts while not transcending all context itself, then the Law of Causality does not preclude the possibility of unprecedented events occurring. And one of those unprecedented events was volitional organisms evolving from ancestors that were far less volitional.

Yes, the laws of physics, the Law of Identity, and the Law of Causality apply both to rocks and human beings. According to the Laws of Identity and Causality, if water splashes on both a rock and me, both the rock and I will have some type of reaction to this stimulus. But it does not follow from this that my reaction to the splash of water has to be as predictable as the reaction from the rock. (A) Looking at reality and (B) observing the respective natures of entities (C) also shows you that I am more complex in my behavior than is the rock. Recognizing the Law of Identity — and with it, the Law of Causality — means recognizing that I possess volitional capabilities that the rock does not possess.

The quotation from Harris at the start of this essay, then, reveals that Harris presents his readers with a false dichotomy: either (x) everything in Existence is governed by consistent principles with predictable responses to their respective stimuli, or (y) everything that happens is random chaos. He refrains from acknowledging the presence of emergent properties. Within most normal contexts, the same principles do keep applying in most situations. Therefore it would be an epistemological folly (which, sadly, is made by many people who call themselves Pragmatists) to reject principles, per se, as useless and unreliable. Nonetheless, while the same principles do consistently apply in most contexts, they do not prevent unprecedented phenomena from occurring. The emergence of organisms from what was previously only nonliving matter, was one such emergent property. The evolution of volition among those organisms, too, is an emergent property.

The quotation from Harris at the start of this essay, then, reveals that Harris presents his readers with a false dichotomy: either (x) everything in Existence is governed by consistent principles with predictable responses to their respective stimuli, or (y) everything that happens is random chaos. He refrains from acknowledging the presence of emergent properties. Within most normal contexts, the same principles do keep applying in most situations. Therefore it would be an epistemological folly (which, sadly, is made by many people who call themselves Pragmatists) to reject principles, per se, as useless and unreliable. Nonetheless, while the same principles do consistently apply in most contexts, they do not prevent unprecedented phenomena from occurring. The emergence of organisms from what was previously only nonliving matter, was one such emergent property. The evolution of volition among those organisms, too, is an emergent property.

Yet Harris and his fans can reply that they do not merely have Spnioza's philosophy on their side. They claim that psychology experiments performed by Benjamin Libet and Chun Siong Soon prove their case. Therefore, let us take a look at those experiments.

Do Benjamin Libet, Chun Siong Soon, and John-Dylan Haynes Disprove Free Will?

In Libet’s original career-making experiment, conducted in 1979, Libet hooked the human test subject up to an electroencephalograph (EEG), which measures brain activity. In this particular experiment, the EEG measured brain waves in the part of the cerebral cortex most strongly associated with one’s readiness to make motor movements with one’s own body. When someone is ready to move a specific muscle, but has not yet moved, the EEG indicates the activation of one’s “readiness potential.” That refers to the readiness to initiate motor movement.

Libet instructed a human test subject to perform a simple motor activity, such as bend the fingers of her right hand or bend her right wrist, whenever she felt like doing so. The test subject also had to look at a clock and remember the specific point in time when she decided consciously to make a specific movement. Libet found from this experiment that the test subject’s readiness potential became active in her brain an average of one-third-of-a-second prior to making the actual movement. Therefrom, Libet concluded that the human test subject’s subconscious mind anticipated what would, an average one-third-second later, be the consciously-recognized decision to make a movement.

In 2008, Chun Siong Soon, John-Dylan Haynes, and the rest of their team ran a more technologically sophisticated version of that experiment. This time, Dr. Soon’s team hooked up the test subject to an fMRI — functional magnetic resonance imaging device — that provides a diagram of exactly what parts of the brain are activated as a person performs a specific motor action or so much as experiences an emotional reaction to some stimulus. When someone performs an action or emotionally reacts, blood flows to specific areas of the brain, and these areas light up in images taken by the fMRI scan.

In 2008, Chun Siong Soon, John-Dylan Haynes, and the rest of their team ran a more technologically sophisticated version of that experiment. This time, Dr. Soon’s team hooked up the test subject to an fMRI — functional magnetic resonance imaging device — that provides a diagram of exactly what parts of the brain are activated as a person performs a specific motor action or so much as experiences an emotional reaction to some stimulus. When someone performs an action or emotionally reacts, blood flows to specific areas of the brain, and these areas light up in images taken by the fMRI scan.

In the experiment, while having their brains fMRI-scanned, human test subjects were to stare at a personal-computer monitor that would flash a series of letters onscreen, one letter at a time. The letter could be any of the 26 of the English alphabet and would be drawn by the computer at random. Simultaneously, the human test subject could, at the same instant that any letter flashed onscreen, press a button. It would be either the button on the left or the one on the right. The test subject would press the button on the left using her left hand, and use the right hand for the right button. Naturally, whether the human test subject chose the right or left is something she did instantaneously. There was no time to plan it out in advance.

Whenever someone pressed a button, the computer recorded whether it was the left or right button. It also recorded the letter that was onscreen at the very same instant. On the fMRI, one region of the brain would light up to indicate the choice of pressing the left button, whereas a separate region would light up to indicate the choice to press the right button. The fMRI scans, too, had their own time stamps recording the exact time of day — down to microseconds — that a specific brain region (for left or right) lit up.

As indicated by the time markers on the fMRI scans, the brain region signifying the left-button-pushing lit up for an average ten seconds prior to the left button actually being pushed. It was vice versa for the right side. This indicates that, an average ten seconds prior to the test subject making a split-second choice, that consciously recognized choice had already been anticipated by the subconscious brain by an average ten seconds.

Your Conscious Mind Didn’t Plan to Buy a House or to Marry That Special Person?

Therefrom, Sam Harris concludes that every person’s course of action is automatically set by one’s subconscious. This is quite absent of, or prior to, one’s own conscious reasoning. Indeed, Harris continues, someone’s conscious reasoning serves as nothing more than a rationalization for courses of action that the subconscious has already thoughtlessly put into motion. Beyond that, Harris maintains, conscious reasoning plays no role in deciding someone’s course of action. Rather, what we wish to believe are our consciously-ratiocinated choices really amount to arational instincts being acted upon.

According to Harris's argument, we have conscious thoughts, sure, but when it comes to every major long-range life decision, such as purchasing a house in a particular neighborhood, what determines these courses of action are not our conscious deliberations but our body chemistry passively reacting to external stimuli. This is just as a cockroach is guided, not primarily by some conscious reasoning, but by its inner, instinctual drives. The cockroach’s seemingly spontaneous actions were a complex emergent property that emerged from the interfaces of components of its body chemistry. Yes, humans have conscious thoughts and cockroaches do not, but Harris maintains that what we have in common with cockroaches is that our courses of action, taken as a whole and looking long-range, are guided mostly by something other than conscious reasoning.

To repeat, those who cite the Libet-Soon experiments to denigrate free will, argue as follows. In the experiments, the exact moment that someone’s decision-making process begins can be precisely ascertained. In Libet’s 1979 experiment, the exact moment the conscious decision-making process began was the moment that the human test subject noticed the time on the clock as she chose to bend her fingers. On that interpretation, the subconscious anticipated the conscious mind by at least one-third of a second. Likewise, in the 2008 Soon-Haynes experiment, the conscious decision-making process began and ended the precise moment the human test subject pressed a button. On that interpretation, the subconscious anticipated the rapid-decision-making conscious mind by an average of ten seconds.

Note that this interpretation assumes that once the brain-measuring instrument detects the activation of “readiness potential,” that necessarily indicates that the decision to make a specific motor movement has already been finalized. To proceed from that assumption would be to deduce that once the readiness potential for moving the left hand is activated, the decision-making process has concluded. It is also to conclude that the motor movement that occurs ten seconds later is not the final stage of the decision, but rather something that happens ten seconds subsequent to the decision-making process’s conclusion.

Such defenders of free will as University of Manchester geriatric medicine professor Raymond Tallis and psychiatrist Sally Satel observe the flaw in any citation of these experiments to prove the allegation that free will does not exist. The flaw is that to cite such experiments as proof of free will’s nonexistence, happens to ignore the contextual and continuous nature of human volition.

To argue that the experiments precisely identified the exact instant in time when a human decision begins (at the noumenal level) and the exact instant when it ends (at the noumenal level), is to presume that any human decision can be observed in isolation from the wider context with which it intertwines.

First off, every choice is made within a larger context and cannot be understood when examined apart from that context. One decision begets the need for other decisions, still. My decision to walk to a grocery store to purchase ice cream begets still other decisions. Now I must decide which flavors I am to purchase and whether I am to purchase the ice cream by means of cash, check, or credit card.

Moreover, what starts out as a small, seemingly trivial decision can expand into a whole sequence of small choices that ultimately culminate in choosing to undertake a major long-range project. For instance, when I was six years old, upon some impulse of her own, my mother gave me some sheets of paper and colored markers and asked me if I wanted to draw. On my own impulse, I went along with that. Without much fussing over my choices or the limits of my resources, I drew an entire series of drawings of some of my favorite video-game characters at the time. Also without thinking much about it, my mother asked me if I would like to staple the drawings together into a book. Again, in the absence of ponderous deliberation, I answered her in the affirmative.

Days later, again without a painstaking weighing of my options, I chose to draw more home-made picture books. Increasingly, I wrote captions to each picture. The captions evolved into sentences. What began as a series of random images evolved into a short story. Through a chain reaction of such events over age six, I decided that my life goal was to be a professional writer. Now, that is a long-range choice that requires years of dedication and various long-range consequences.

To stay true to that choice throughout one’s adult life does require painstaking deliberation and a serious weighing of options. Following through on this long-range choice also encompasses an entire series of steps wherein I make smaller, easier choices, such as what sort of font I might use when I type out a manuscript.

Entities and their actions are interrelated in a wider context. One action of a specific entity relates to that entity’s other actions, being an effect of prior actions and a cause of subsequent actions. During waking experience, the decision-making process is therefore an ongoing, continuous process. It is not as if, during a single duration of time in which I am awake, my volition starts, stops, and then starts again. Therefore, volition itself is an ongoing, continuous process that requires no noumenal-level beginnings or endings. Within the span of your waking experience, the volitional process exists holistically, as a continuum. As a corollary, you cannot, on some noumenal level, pinpoint the exact moment when the process of a making a specific decision begins.

Often, the implicit and initially superficial recognition of having to make that choice starts out vague and faint. The urgency of the need for a committed position on the decision becomes clearer and more apparent over time, as more sensory evidence accumulates. If, between February 1 and March 1, I notice I have made a net gain of four pounds in weight, the need to decide whether I will change my eating or exercise habits will not be obvious. I might give it some passing thoughts before temporarily forgetting about it. Should I gain thirty pounds between March 2 and April 2, though, then recognition of the need for a long-range decision becomes starker.

Whenever someone pressed a button, the computer recorded whether it was the left or right button. It also recorded the letter that was onscreen at the very same instant. On the fMRI, one region of the brain would light up to indicate the choice of pressing the left button, whereas a separate region would light up to indicate the choice to press the right button. The fMRI scans, too, had their own time stamps recording the exact time of day — down to microseconds — that a specific brain region (for left or right) lit up.

As indicated by the time markers on the fMRI scans, the brain region signifying the left-button-pushing lit up for an average ten seconds prior to the left button actually being pushed. It was vice versa for the right side. This indicates that, an average ten seconds prior to the test subject making a split-second choice, that consciously recognized choice had already been anticipated by the subconscious brain by an average ten seconds.

Your Conscious Mind Didn’t Plan to Buy a House or to Marry That Special Person?

Therefrom, Sam Harris concludes that every person’s course of action is automatically set by one’s subconscious. This is quite absent of, or prior to, one’s own conscious reasoning. Indeed, Harris continues, someone’s conscious reasoning serves as nothing more than a rationalization for courses of action that the subconscious has already thoughtlessly put into motion. Beyond that, Harris maintains, conscious reasoning plays no role in deciding someone’s course of action. Rather, what we wish to believe are our consciously-ratiocinated choices really amount to arational instincts being acted upon.

According to Harris's argument, we have conscious thoughts, sure, but when it comes to every major long-range life decision, such as purchasing a house in a particular neighborhood, what determines these courses of action are not our conscious deliberations but our body chemistry passively reacting to external stimuli. This is just as a cockroach is guided, not primarily by some conscious reasoning, but by its inner, instinctual drives. The cockroach’s seemingly spontaneous actions were a complex emergent property that emerged from the interfaces of components of its body chemistry. Yes, humans have conscious thoughts and cockroaches do not, but Harris maintains that what we have in common with cockroaches is that our courses of action, taken as a whole and looking long-range, are guided mostly by something other than conscious reasoning.

To repeat, those who cite the Libet-Soon experiments to denigrate free will, argue as follows. In the experiments, the exact moment that someone’s decision-making process begins can be precisely ascertained. In Libet’s 1979 experiment, the exact moment the conscious decision-making process began was the moment that the human test subject noticed the time on the clock as she chose to bend her fingers. On that interpretation, the subconscious anticipated the conscious mind by at least one-third of a second. Likewise, in the 2008 Soon-Haynes experiment, the conscious decision-making process began and ended the precise moment the human test subject pressed a button. On that interpretation, the subconscious anticipated the rapid-decision-making conscious mind by an average of ten seconds.

Note that this interpretation assumes that once the brain-measuring instrument detects the activation of “readiness potential,” that necessarily indicates that the decision to make a specific motor movement has already been finalized. To proceed from that assumption would be to deduce that once the readiness potential for moving the left hand is activated, the decision-making process has concluded. It is also to conclude that the motor movement that occurs ten seconds later is not the final stage of the decision, but rather something that happens ten seconds subsequent to the decision-making process’s conclusion.

Such defenders of free will as University of Manchester geriatric medicine professor Raymond Tallis and psychiatrist Sally Satel observe the flaw in any citation of these experiments to prove the allegation that free will does not exist. The flaw is that to cite such experiments as proof of free will’s nonexistence, happens to ignore the contextual and continuous nature of human volition.

To argue that the experiments precisely identified the exact instant in time when a human decision begins (at the noumenal level) and the exact instant when it ends (at the noumenal level), is to presume that any human decision can be observed in isolation from the wider context with which it intertwines.

First off, every choice is made within a larger context and cannot be understood when examined apart from that context. One decision begets the need for other decisions, still. My decision to walk to a grocery store to purchase ice cream begets still other decisions. Now I must decide which flavors I am to purchase and whether I am to purchase the ice cream by means of cash, check, or credit card.

Moreover, what starts out as a small, seemingly trivial decision can expand into a whole sequence of small choices that ultimately culminate in choosing to undertake a major long-range project. For instance, when I was six years old, upon some impulse of her own, my mother gave me some sheets of paper and colored markers and asked me if I wanted to draw. On my own impulse, I went along with that. Without much fussing over my choices or the limits of my resources, I drew an entire series of drawings of some of my favorite video-game characters at the time. Also without thinking much about it, my mother asked me if I would like to staple the drawings together into a book. Again, in the absence of ponderous deliberation, I answered her in the affirmative.

Days later, again without a painstaking weighing of my options, I chose to draw more home-made picture books. Increasingly, I wrote captions to each picture. The captions evolved into sentences. What began as a series of random images evolved into a short story. Through a chain reaction of such events over age six, I decided that my life goal was to be a professional writer. Now, that is a long-range choice that requires years of dedication and various long-range consequences.

To stay true to that choice throughout one’s adult life does require painstaking deliberation and a serious weighing of options. Following through on this long-range choice also encompasses an entire series of steps wherein I make smaller, easier choices, such as what sort of font I might use when I type out a manuscript.

Entities and their actions are interrelated in a wider context. One action of a specific entity relates to that entity’s other actions, being an effect of prior actions and a cause of subsequent actions. During waking experience, the decision-making process is therefore an ongoing, continuous process. It is not as if, during a single duration of time in which I am awake, my volition starts, stops, and then starts again. Therefore, volition itself is an ongoing, continuous process that requires no noumenal-level beginnings or endings. Within the span of your waking experience, the volitional process exists holistically, as a continuum. As a corollary, you cannot, on some noumenal level, pinpoint the exact moment when the process of a making a specific decision begins.

Often, the implicit and initially superficial recognition of having to make that choice starts out vague and faint. The urgency of the need for a committed position on the decision becomes clearer and more apparent over time, as more sensory evidence accumulates. If, between February 1 and March 1, I notice I have made a net gain of four pounds in weight, the need to decide whether I will change my eating or exercise habits will not be obvious. I might give it some passing thoughts before temporarily forgetting about it. Should I gain thirty pounds between March 2 and April 2, though, then recognition of the need for a long-range decision becomes starker.

Even when we consider such sophisticated scientific instruments as EEGs and the fMRI, such machines cannot ascertain, on the noumenal level, the exact beginnings or endings of the process of coming to a specific decision. These beginnings and endings bleed together into a continuous whole. This is just as how, although a pet dog is made out of atoms, we cannot, through unaided senses, discern where one atom of the dog begins and another ends.

That my subconscious might anticipate my conscious mind in recognizing my need to make a long-range decision of life-changing consequences, does not preclude the necessity of applying conscious deliberation to such a decision. Yes, long before my conscious mind responds, my subconscious might (1) prove sensitive and responsive to the environment, (2) send signals to my conscious mind, and (3) prepare my body for specific motor movements. That my subconscious responded to something prior to my conscious mind responding to it, and then readied my conscious mind for conscious thought, does not mean that my subconscious overrode my conscious mind and “therefore made the decision for me.” My conscious mind still has to be there to weigh each option and contemplate the consequences of taking any option.

Moreover, contrary to Sam Harris, it is not a matter of a woman’s subconscious proactively leading her in her course of action and of her conscious mind passively following along and rationalizing decisions that have already been finalized. Rather, it is a matter of both one’s conscious mind and one’s subconscious both being active during one’s waking experience. It is also a matter of the conscious mind remaining proactive in deciphering signals sent from the subconscious. It is also a matter of the conscious mind weighing options and judging which subconsciously-motivated impulses are or are not safe to act upon. Then it is up to the conscious mind to decide proactively which desires should or should not be acted upon, which vaguely-considered plans should be provided further detail and ultimately implemented.

A Complex, Volitional Choice Doesn’t Require a Conscious Account of Every Motor Movement, . . . Let Alone Every Conscious Motor Movement Being Thought Up Prior to the Subconscious’s Activation of Your “Readiness Potential”

It would be silly to conclude that a long-range goal is not consciously chosen if not every single motor movement that contributes to meeting that long-range goal is consciously-thought-out and planned. Here is an example that Raymond Tallis provides. Today I might decide to walk to the grocery store. On my trip there, it is not as though I consciously think about every single step I take. I do not think “Now I bend my left knee. Now I raise my left foot above the ground. Now I place my left foot on the ground again, but farther ahead than it was previously. Now for the right foot...” On this trip to the grocery store, explicates Raymond Tallis, “there isn’t a separate decision corresponding to every one of the hundreds of steps” taken to get there (page 249). That I do not consciously think out every literal step, does not prove that conscious thought played no role in the overall, larger goal of making the trip from my home to this retail establishment.

Likewise, as I type the first draft of this essay, I do not consciously think out every stroke of every key as I type. It is not as though I must tell myself, “First I will type the F key. Then I will type the I key. Then I will type the R key...” I just type. I do not agonize over every single sentence. I just type out the sentences as they pop into my head. Agonizing over specific word choices or grammatical choices comes later, upon rereading and editing the draft. Recognizing the fact that my commitment to writing was and is an overall conscious choice, does not hinge upon believing that every specific procedure involved had to be consciously thought-out prior to my cerebral cortex activating the “readiness potential” of my fingers.

Yes, the subconscious parts of my brain might activate before my conscious mind becomes aware of it, as my body makes specific motor movements. Yet it is a tremendous leap to conclude from this that my decades-long dedication to becoming a writer — a choice first made years ago, and a choice that is renewed every day — was a choice not made by me but rather simply a course action that my subconscious simply programmed me, before the fact, to undertake. When we look at the wider context of long-range life decisions, the results of Libet’s and Soon’s neuroscience experiments cannot erase the conscious thought that went into my making, and my renewing my commitment to, various choices that I know will affect me for years to come.

The Concept Theft Involved in Trying to Convince Me, Consciously, That My Consciousness Is Not in Charge

And, again, there is a self-refutation in Harris’s own attempt to explain his conclusion verbally. The snag is that Harris’s explanation appeals to his readers’ and audiences’ conscious cognition. Should it be the case that one’s courses of action are determined by the subconscious, and conscious reasoning has no influence in that, then it is self-defeating for Harris to attempt to explain his argument.

According to Harris’s own logic, his reader’s subconscious will predetermine agreement or disagreement with his opinion prior to Harris being able to finish his articulation. That would thereby render it superfluous, before the fact, for Harris to explain himself. As Wayne Dunn puts it,

Ultimately, Harris overlooks that when it comes to long-term decisions, such as purchasing the right home, human beings often do employ their conscious reasoning for the purposes of making their final decision. Moreover, their conscious reasoning does influence them insofar as the conscious reasoning provides a check against following one’s impulses. That is exactly why, when one deliberates over a decision that requires an enormous investment of money and years’ worth of commitment, someone is capable of changing her mind.

On September 1, 2017, I added the quotation from Spinoza. On November 20, 2017, I changed every instance where I used the expression “Law of Causation” to “Law of Causality.” On Sunday, July 25, 2021, I changed the grammar. I shortened the sentences.

That my subconscious might anticipate my conscious mind in recognizing my need to make a long-range decision of life-changing consequences, does not preclude the necessity of applying conscious deliberation to such a decision. Yes, long before my conscious mind responds, my subconscious might (1) prove sensitive and responsive to the environment, (2) send signals to my conscious mind, and (3) prepare my body for specific motor movements. That my subconscious responded to something prior to my conscious mind responding to it, and then readied my conscious mind for conscious thought, does not mean that my subconscious overrode my conscious mind and “therefore made the decision for me.” My conscious mind still has to be there to weigh each option and contemplate the consequences of taking any option.

Moreover, contrary to Sam Harris, it is not a matter of a woman’s subconscious proactively leading her in her course of action and of her conscious mind passively following along and rationalizing decisions that have already been finalized. Rather, it is a matter of both one’s conscious mind and one’s subconscious both being active during one’s waking experience. It is also a matter of the conscious mind remaining proactive in deciphering signals sent from the subconscious. It is also a matter of the conscious mind weighing options and judging which subconsciously-motivated impulses are or are not safe to act upon. Then it is up to the conscious mind to decide proactively which desires should or should not be acted upon, which vaguely-considered plans should be provided further detail and ultimately implemented.

A Complex, Volitional Choice Doesn’t Require a Conscious Account of Every Motor Movement, . . . Let Alone Every Conscious Motor Movement Being Thought Up Prior to the Subconscious’s Activation of Your “Readiness Potential”

It would be silly to conclude that a long-range goal is not consciously chosen if not every single motor movement that contributes to meeting that long-range goal is consciously-thought-out and planned. Here is an example that Raymond Tallis provides. Today I might decide to walk to the grocery store. On my trip there, it is not as though I consciously think about every single step I take. I do not think “Now I bend my left knee. Now I raise my left foot above the ground. Now I place my left foot on the ground again, but farther ahead than it was previously. Now for the right foot...” On this trip to the grocery store, explicates Raymond Tallis, “there isn’t a separate decision corresponding to every one of the hundreds of steps” taken to get there (page 249). That I do not consciously think out every literal step, does not prove that conscious thought played no role in the overall, larger goal of making the trip from my home to this retail establishment.

Likewise, as I type the first draft of this essay, I do not consciously think out every stroke of every key as I type. It is not as though I must tell myself, “First I will type the F key. Then I will type the I key. Then I will type the R key...” I just type. I do not agonize over every single sentence. I just type out the sentences as they pop into my head. Agonizing over specific word choices or grammatical choices comes later, upon rereading and editing the draft. Recognizing the fact that my commitment to writing was and is an overall conscious choice, does not hinge upon believing that every specific procedure involved had to be consciously thought-out prior to my cerebral cortex activating the “readiness potential” of my fingers.

Yes, the subconscious parts of my brain might activate before my conscious mind becomes aware of it, as my body makes specific motor movements. Yet it is a tremendous leap to conclude from this that my decades-long dedication to becoming a writer — a choice first made years ago, and a choice that is renewed every day — was a choice not made by me but rather simply a course action that my subconscious simply programmed me, before the fact, to undertake. When we look at the wider context of long-range life decisions, the results of Libet’s and Soon’s neuroscience experiments cannot erase the conscious thought that went into my making, and my renewing my commitment to, various choices that I know will affect me for years to come.

The Concept Theft Involved in Trying to Convince Me, Consciously, That My Consciousness Is Not in Charge

And, again, there is a self-refutation in Harris’s own attempt to explain his conclusion verbally. The snag is that Harris’s explanation appeals to his readers’ and audiences’ conscious cognition. Should it be the case that one’s courses of action are determined by the subconscious, and conscious reasoning has no influence in that, then it is self-defeating for Harris to attempt to explain his argument.

According to Harris’s own logic, his reader’s subconscious will predetermine agreement or disagreement with his opinion prior to Harris being able to finish his articulation. That would thereby render it superfluous, before the fact, for Harris to explain himself. As Wayne Dunn puts it,

Determinists hold that man’s every thought and action is necessitated by factors beyond his control. Yet, curiously, a determinist typically cites “evidence” for his philosophical convictions. To which you might respond: “So, let me get this straight. Only after scrupulously ‘weighing’ the facts did you conclude that determinism is true, correct?” When he says yes, he’s busted. For if determinism is true, then one could not “weigh” the facts: all one’s opinions are pre-set, including opinions on determinism. Choosing to believe that men lack volition is a contradiction in terms. (And choosing to evade the issue is also a choice.)True, people often have particular emotional predispositions toward particular courses of action that antecede their rational thoughts about the matter. Also true, it is common for people to employ conscious reasoning, not to reconsider their choices but merely to rationalize their immediate preconceptions or the beliefs to which they have already committed themselves for years.

Ultimately, Harris overlooks that when it comes to long-term decisions, such as purchasing the right home, human beings often do employ their conscious reasoning for the purposes of making their final decision. Moreover, their conscious reasoning does influence them insofar as the conscious reasoning provides a check against following one’s impulses. That is exactly why, when one deliberates over a decision that requires an enormous investment of money and years’ worth of commitment, someone is capable of changing her mind.

On September 1, 2017, I added the quotation from Spinoza. On November 20, 2017, I changed every instance where I used the expression “Law of Causation” to “Law of Causality.” On Sunday, July 25, 2021, I changed the grammar. I shortened the sentences.