For many people who revile the idea of respecting the pronouns of trans- and non-binary people, I have a wager. It is not like Pascal’s Wager. I do not claim that if you do as I ask, and it turns out later that I was wrong, you will have lost nothing anyway. However, I do ask the following. First, look at the results of doing as I ask, only for it to turn out I was wrong. Then look at the results of not doing as I ask, only for it to turn out that it was those who disrespect trans people’s pronouns who turned out to be wrong. Then compare the bad consequences of the first outcome against the second.

People are trans if, psychologically, they find themselves identifying as a gender opposite from the sex that they were assigned at birth. The term trans is used because that prefix means “across from.” That is, their gender is one that is across from the sex that they were assigned. By contrast, I am a cisgendered male — “cis” for short. The cis- prefix means “on the same side of.” You are cis- if the gender with which you identify is the very same as the sex that you were assigned at birth. Non-binary people are not technically trans; they do not identify their gender as either male or female.

For now, let’s leave aside issues about any series of gender reassignment surgeries and any issues about trans women competing in athletics against cis women. For the moment, let’s look at pronouns.

What I ask you is that you respect the pronouns that a trans person specifies. If you happen upon a trans woman who asks to be called “she” and “her,” please do so.

No, I often hear in response. The retort is that transgenderism is, at best, a delusion. According to this insistence, a trans woman is necessarily male in every pertinent context. The problem, it is said, is that this trans woman possesses some sort of mental illness or delusion that “he” is a woman. This is comparable, it is often said, to able-bodied people who feel that it is “wrong” to have all their limbs and who have the desire to have a perfectly healthy limb surgically amputated (this is a real mental illness).

According to that interpretation, it is not just annoying to comply with calling a trans woman by her requested pronouns; it is wrong. It is wrong, we are told, because to call this “delusional man” a “she” is to reinforce and enable “his” “delusion.” After all, aren’t genitalia the deciding factor in determining whether someone is male or female?

My response is as follows. There is indeed scientific evidence for a physiological basis in transgenderism. Other parts of the anatomy can be overridden by brain structure and brain chemistry. Since the 1990s, neurologists have found, from data collected in autopsies, that a trans woman’s brain has greater physiological similarity to a cis woman’s brain than a cis man’s. The greater similarity is in the structure in the brain called the BSTc — the Central subdivision of the Bed nucleus of the Stria Terminalis.

Now let’s imagine, for argument’s sake, that it turns out that I am wrong. And let’s say that you have indeed done as I asked, and called trans people by their preferred pronouns. What is the worst that could happen? The worst that would happen was that for some brief moment, yes, you did provide some trivial and fleeting reinforcement to someone’s “delusion.” And then you went on with your day. And maybe this subtle change in the culture might contribute to larger changes, such as there being more trans women competing against cis female athletes.

But let’s imagine that I’m correct, and you don’t do as I asked. What’s the worst that could happen from that? It’s already a fact that, their entire lives, trans people have been continually invalidated, often even by members of their own families, sometimes their own parents. These people are frequently told that they don’t know their own minds and don’t understand their own thoughts. To be hit on the head with this, over and over, for decades, leaves scars. And if I’m right, and you disrespect trans people’s pronouns, you will have made a contribution to this lifetime of invalidation, denial, ridicule, and abuse.

Again, I’m not Blaise Pascal. I’m not claiming that if you do as I ask, and it turns out I’m wrong, that you’ve lost nothing anyway. But I am asking you to weigh the cost of me being wrong versus the cost of it being wrong to disrespect trans people’s pronouns.

Monday, December 27, 2021

Saturday, December 25, 2021

Bittersweet Thoughts for This Christmas

Stuart K. Hayashi

This Christmas will be my first without my mother on this earth. I miss her. But I’m grateful she was my mother. I’m thankful for so many of the choices she made.

Saturday, September 25, 2021

Clearing Up the Difference Between Utility Patents and Design Patents – Neither Is a Monopoly

Stuart K. Hayashi

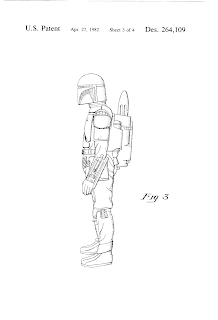

Note that the U.S. patent number is US D264,109 S. The D following the US is important. By the end of the essay, we will return to why that is.

A common misunderstanding is that a patent is a claim of ownership over the general idea for an entire product category. According to this misinterpretation, someone gaining a patent on her electric can-opener amounts to the government proclaiming that she now owns the vague idea of “electric can-opener.” The same would happen if she gained a patent on her paperclip. From this comes a second misunderstanding, that the patent confers upon its owner a government-enforced monopoly over an industry. The patent holder would then be able to sue any other vendors who produce, without her permission, their own electric can-openers and their own paperclips. Worse, the patent holder would be able to sue these competitors successfully even if they arrived at their own designs independent of any observation of the patent holder’s model.

I have disputed those misunderstandings in previous blog posts (1, 2,3, 4, 5).

A patent is on a specific design of a feature or function of a product and does not impose a State-enforced monopoly on an industry or product category. A vendor can compete against any patent holder by coming up with a design that is similar but is not an exact duplicate.

Still, sometimes I get yet another response. This one comes less often from libertarian anarchists opposed to patent rights and more often from more commonsensical people who recognize the need for some form of intellectual property. The response is that there are two types of U.S. patents — design patents and utility patents. According to the rejoinder, it is true that a design patent is merely on a specific design only. However, the rejoinder continues, a utility patent really is a claim of ownership over a general idea, and it does grant its owner a government-enforced monopoly over an industry.

It is true that there are both design patents and utility patents. And it is true that there is a distinction between them. However, the distinction provided above is not accurate. Rather, the purported distinction above comes from a misunderstanding of what a utility patent truly is and a misunderstanding of the extent to which enforcement of utility patents can be broader than it is for design patents.

In the end, both design patents and utility patents provide protection for a specific design feature. Neither claim ownership on a whole product category or industry.

I now will attempt to provide a more accurate explanation of the difference between design patents and utility patents. I will also try to explain how the mistaken conclusion that a utility patents provides its owner a monopoly originates from a misinterpretation of this distinction and of how utility patents are defined.

Design Patents

Design patents are on specific features directly observable by the senses. That is, for you to infringe on my design patent, units of your product have to resemble mine very closely in terms of how they look, feel, etc. For that reason, design patents are usually used to protect a design’s aesthetic qualities. One example is the design patent awarded to George Lucas for his Boba Fett action figure.

Design patents are on specific features directly observable by the senses. That is, for you to infringe on my design patent, units of your product have to resemble mine very closely in terms of how they look, feel, etc. For that reason, design patents are usually used to protect a design’s aesthetic qualities. One example is the design patent awarded to George Lucas for his Boba Fett action figure.

That a design patent is about protecting properties of the design that are readily perceptible is also visible in other instances. Consider the ones recognizing fashion-apparel-and-lifestyle mogul Ralph Lauren’s ownership over this cologne bottle and this bed. Their U.S. patent numbers are, respectively, US D 259,098 S and US D 319,932 S.

Its sculptor, Auguste Bartholdi, even applied for and received a US design patent on the Statue of Liberty. That is US D 11,023.

It was not that Auguste Bartholdi expected that the U.S. federal government would enforce some monopoly on giant statues. Rather, suggests Kelsey Campbell-Dollaghan in Gizmodo it was that to finance the completion of the statue, Bartholdi sold small replicas of it as souvenirs. He did not want knockoffs of it being sold when he needed to recoup his investment. This is, again, because the design patent is intended to restrict the copying of the product’s aesthetic qualities rather than its operation and functionality. the

Once again note the D subsequent to the US. That is a trait common to all U.S. design patents. You will notice a different numbering convention for U.S. utility patents.

Utility Patents

Speaking of which, a utility patent protects a specific design feature with respect to a unit’s practical functionality — its utility, hence the name. What is being protected is a specific combination of engineering principles as applied to a particular design feature in the utility patent.

Speaking of which, a utility patent protects a specific design feature with respect to a unit’s practical functionality — its utility, hence the name. What is being protected is a specific combination of engineering principles as applied to a particular design feature in the utility patent.

As principles are more abstract than the appeal to the senses that are readily observable in a design patent, the aspects of a design that a utility patent protects can be interpreted more broadly than what is typical for a design patent.

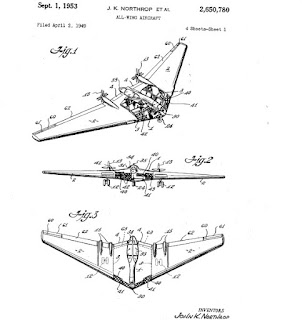

As examples of utility patents, I will provide two that Jack Northrop had on his airplanes that were “all wing.”

These patents on his airplanes did not award Northrop a government-enforced monopoly on the production of airplanes. What these patents did mean was that Northrop had civil recourse if the totality all the engineering principles he employed were being copied by yet another vendor against his consent.

Two patents Northrop had on this sort of product were US 2,406,506 A and US 2,650,780 A.

Note the absence of a D after the US in the U.S. patent number.

That is how, just by looking at the U.S. patent number, you can tell if it is a design patent or a utility patent. For design patents, there is a D or Des. directly following the US (see here for Des. appearing). For utility patents, that is not present.

Evidence That a Utility Patent Is Not a Monopoly

This is the summary. The protected design attributes of a design patent can be readily perceived by the senses. To determine if a vendor peddled a knockoff of the cologne bottle on which Ralph Lauren had a design patent, all you need to do is look at both Ralph Lauren’s cologne bottle and that other vendor’s. Ditto in instances where George Lucas accused a vendor of producing unlicensed knockoffs of the Boba Fett action figure. Most often, the desired effect of the design protected by a design patent is an aesthetic or artistic one.

This is the summary. The protected design attributes of a design patent can be readily perceived by the senses. To determine if a vendor peddled a knockoff of the cologne bottle on which Ralph Lauren had a design patent, all you need to do is look at both Ralph Lauren’s cologne bottle and that other vendor’s. Ditto in instances where George Lucas accused a vendor of producing unlicensed knockoffs of the Boba Fett action figure. Most often, the desired effect of the design protected by a design patent is an aesthetic or artistic one.

By contrast, the protected design attribute of a utility patent is its particular arrangement of parts in order to employ specific principles of science and engineering. And the effect is a practical one. The effect of the design protected in a utility patent is one of utility. Because the engineering principles specified in the utility patent are more abstract and less readily observable than what is found in design patents, there is greater room for interpretation when it comes to how courts decide if someone’s utility patent has been violated. More often than with design patents, engineers and other experts with specialized knowledge pertinent to the industry in which the invention is used must be called upon to determine if a utility patent is infringed. This is why enforcement of utility patents are usually broader than it is with design patents.

And that a utility patent can be interpreted more broadly than a design patent is where the confusion comes from. The confusion becomes the misconception that a utility patent does give the holder of a utility patent a monopoly on an entire industry.

But here’s the reality. Below is a table I made of U.S. utility patents on electric can-openers.

Note that the interval between every new U.S. utility patent on electric can-openers and the previous one is shorter than 17 years. That is, every U.S. utility patent listed was issued prior to the expiration of the previous one. That happened even though all of these are US utility patents on “the electric can-opener.” That is because no US utility patent ever gave a party a State-enforced monopoly on the whole product category or industry of “electric can-openers.”

We find the same pattern in U.S. utility patents for paperclips, another invention for which I made a similar table.

Despite utility patents being interpreted more broadly than design patents in the matter of enforcement, having a US utility patent does not give any party a monopoly on the general idea of for a whole product category. It is not a government-enforced monopoly over an industry.

On Friday, November 19, 2021, I added the section about the U.S. design patent on the Statue of Liberty.

Friday, September 10, 2021

Being ‘Free’ to Transmit COVID Unrestricted Is the Actual Imposition Forced on Others

Stuart K. Hayashi

Sometimes the local Honolulu news will cover some self-deluded people. Some of these people spread conspiracy theories that deny the scientific evidence about COVID-19. Many more of these people reject, out of hand, the very idea of there being necessary rules to prevent the spread of this disease.

Every time such people appear on the news, I brace myself anxiously. In several instances, as I anticipated, among these self-deluded people are ones I have met at free-market libertarian meetings. At the time, those people seemed sane and I was friendly with them. Material such as this and this fills me with sadness and regret.

As have they, I am experiencing culture shock in adjusting to the rules that mitigate COVID’s spread. I never liked wearing a surgical mask. But unlike those acquaintances of mine, I recognize that this aversion to culture shock does not justify acting on motivated reasoning to rationalize this hatred for such rules.

I do have qualified qualms about such rules coming on from the top down in a command-and-control, one-size-fits-all fashion. In a political system closer to the one I favor, this would be the alternative. Insofar as contact tracing can be used to prove a case, a household that contracts a dangerous pathogen from an unvaccinated party should be able to hold that unvaccinated party liable for it.

A party that refuses a vaccine that is readily available is a party that cuts its own costs and imposes those costs on other people in the form of posing a danger to them. The victim suing the unvaccinated transmitter for damages simply transfers those costs back to the unvaccinated party.

When it comes to COVID, civil liability should also apply to businesses where large crowds gather. If a business allows for a gathering of twenty or more people at once, then that business should be held civilly liable if contact tracers find that someone contracted COVID from an event that the business hosted. No matter what excuse that business’s owner makes, the legal doctrine of Strict Liability should apply.

In my estimation, those are the ideal remedies. But, absent of my proposal being adopted, the next best alternative is indeed for the government to have these top-down, command-and-control rules to mitigate COVID’s spread. I mean mask mandates, vaccine mandates, and often even stay-at-home orders. These rules are a wiser alternative than what many of these COVID-deniers seem to want: for there to be no COVID rules, just as life was in late 2019, and for them to be “free” to go around and transmit COVID with impunity.

Can COVID restrictions go too far? Can there be unreasonable ones? Yes, there can be. Of course a COVID restriction cannot be inherently above any criticism or call for amendment. Robert W. Tracinski noted last year how Michigan’s governor Whitmer

COVID rules can become too overbearing. But the same can occur with traffic laws and pollution reduction. Incompetent legislators could pass many traffic laws so severe as to make life nearly impossible for motorists. Likewise, top-down command-and-control pollution regulations can become onerous to the point where they drive industrial production to a halt.

But, again, if a purely individualistic privatization solution cannot gain political favor, the next best alternative is not to repeal all traffic laws and all anti-pollution measures. It is to have these laws renegotiated and rewritten so that all parties’ concerns can be addressed more adequately. That is how it should be with COVID rules.

Nor it is practical simply to say, “Stay-at-home orders should apply only to the elderly.” No, the elderly are protected to the degree that COVID rules apply to everyone.

I still support free enterprise. Free enterprise does not include “freedom” from rules to protect people from COVID. When I hear denials of reality from so many libertarians and Objectivists whose judgment I had previously trusted, I feel ashamed.

A LibertarKaren on Twitter: “You don’t have a right to be free from respiratory viruses.”

My reply:

My friend Pablo Wegesend, another Hawaii resident, is right on.

issued a confusing and highly intrusive executive order that required stores to rope off sections containing “nonessential” items, banned travel between households, and banned landscapers from working. The chief complaint is that Whitmer banned activities based on how “essential” or “nonessential” she deemed them to be, rather than on whether they could be conducted safely.One can reasonably criticize specific measures as being poorly thought out or poorly implemented. It is entirely misguided, though, to pronounce — as too many self-proclaimed Objectivists and free-marketers have — that the COVID-19 restrictions are wrong or unjust in principle, as if everything would be better if there were no more such rules than there were in early 2019.

As the transmission of fatal pathogens is indeed an initiation of force, it is legitimate that government force be used to counter that spread. The issue is how government force can be used most properly. It is foolish to pretend that it would be preferable if the government did nothing about this.

This should not be so difficult for self-proclaimed libertarians and free-marketers to understand. It’s common for them to say, “In our ideal world, all roads would be privately owned. And the private owner of the road would set the rules for it, such as how fast people may drive on it. But as long as roads are controlled by the government, the government should have these command-and-control speed limits and laws against drunk driving.” The same principle applies to curbing the advancement of COVID contractions.

It likewise applies to the issue of pollution. Much of the air and most waterways and other water resources are government-owned. This collectivism disincentives people from taking care of such resources. In a purely capitalist society, these resources would be private belongings of various parties. If a company polluted the air or water of a privately owned spaced, the private owner would have every incentive to sue the polluter for damages.

But absent of this pure privatization, there should be these top-down, command-and-control laws that limit the pollution of the air and water. That is better than the air and water resources remaining publicly owned combined with industrial plants being able to pollute them “freely.”

Actually I do have the right to use State force to obstruct you from transmitting a fatal pathogen to others. That is just as I have a right not to be run over by a drunk driver and not have my drinking water accidentally poisoned by an industrial plant. https://t.co/TSOpV5OyRT

— $tuart K. Hayashi🌎💱 (@legendre007) September 10, 2021

I like ideas for libertarian things like entrepreneurship... I’m against the War on Drugs. I’m against any government’s war on consensual activities of adults. “Consensual” is the word. I don’t consent to have a contagious virus spread to me. ... This [the set of COVID rules, contrary to recent hyperbole] is not Nazi Germany. This is not living under the Taliban. ... Cases are going up. Take it seriously.

On September 28, 2021, I added the links to the regrettable COVID-denialist postings on Instagram from fellow Hawaii residents.

Sunday, June 13, 2021

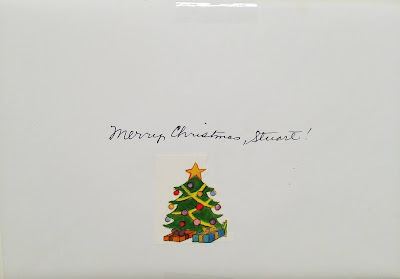

Mom’s Christmas Card Thanking Me for Informing Her of What Was ‘Interesting’

Stuart K. Hayashi

As I have written before, my mother, who died on January 12 of this year, valued holiday greeting cards much more than I did. I have also written of my regret in not appreciating enough how, over the past decade, she increasingly wrote personalized notes inside the cards she gave me.

I have been reflecting on my life and have worried my major choices may have been a disappointment to my mother and, maybe worse, to myself. Since I last blogged about this, I found yet another Christmas card she wrote me that has helped partially restore my confidence that my mother believed in me. I started thinking about this one a lot on June 12 of this year.

Dec. 2016.

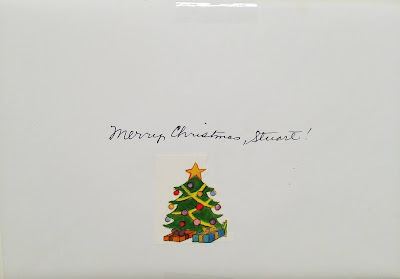

This is the front of the card.

This is the envelope.

It says,

Dec. 2016Dear Stuart –Thank you for being such a great son and person! Thank you for doing the dishes, “DVRing” shows for us, keeping us company so we don’t get lonely, informing us of a lot of interesting things, and just being here with us. We are very lucky to have you.

Please go ahead and order the books you wanted and enjoy them.

Hope you have a great Christmas and the kind of new year you want. Wishing you good health, prosperity, success and happiness in the new year and always!

Merry Christmas with love,

Mom + Dad

Thursday, June 03, 2021

My Mother’s Funeral: The Speech I Gave For It

Stuart K. Hayashi

I did not give the eulogy for my mother’s funeral. My cousin Wayne Nishioka did. But I did give the speech directly preceding his. Below is that speech. I did not have a written transcript but went by an outline. I rehearsed so many times, though, that I did memorize many sentences. This is the speech to the best of my recollection. I delivered it wearing my face mask.

Our mother rose from poverty and hardship, and became the first person in her family to attend university. She did it to become a teacher. She prided herself on being a teacher. And I think she became a teacher, in large part, because of her love for children. Before she raised my sister and me, she helped with our cousins Wayne, Mark, and April. And, years later, she helped with April’s daughter Arissa.

And she wasn’t a teacher just in the classroom. She taught important lessons through the example that she set. I want to talk about our mother, and how I think she exemplified supportiveness, strength, confidence, and wisdom.

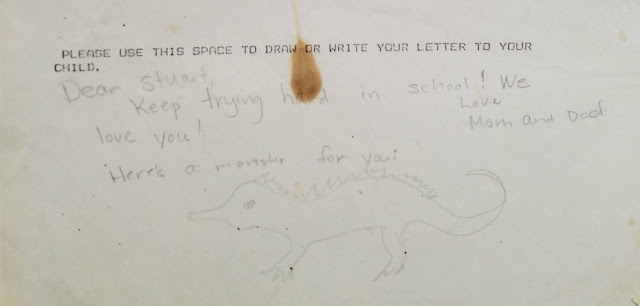

About supportiveness . . . . Ever since I was little, I drew dragons and monsters. Many of my classmates and teachers thought that was weird. I was even bullied over it. I think many mothers would have tried to discourage it. “Why are you being so weird?” And our mother didn’t really understand it. But she didn’t try to discourage it. Often she encouraged it.

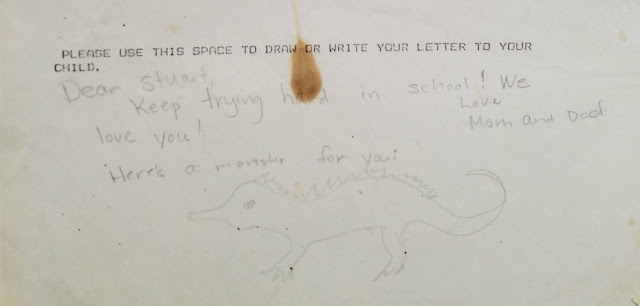

I remember open house night. Open house night is a school night when the students’ parents visit the teacher and talk about their child. On open house night, my first-grade teacher put a paper on each student’s desk saying “Please draw or write something to encourage your child.” And Mom wrote, “Stuart, I drew a monster for you.” And she did. [It turns out she wrote, “Here’s a monster for you.”] And it was well-done, too. That was the kind of person she was.

And our mother was full of confidence. Whenever a business shortchanged us, Mom wouldn’t let it slide. She would call that business and address it. She was firm and she was polite.

Our mother’s confidence was not what people conventionally imagine. Mom often worried about our father, my sister, and me, and with good reason. And that worry was often very visible. You could see it on her face. You could hear it in her voice. But that worry and fear never froze into inaction. She was scared and worried and yet she took action.

To my knowledge, she didn’t put on some “brave face.” There was no pretense about it. I was impressed by how upfront she was about the situation. She was worried and she did what she needed to do. And I thought, “Wow, that’s REAL confidence.” [I wanted to mention this part, but forgot to do so: And Mom letting her worry show, showed a real trust. That she was worried and took action was exactly why I felt safer around her than anyone else, even when the situation seemed dire. I would be surprised if I found that with anyone else.]

[I point to the symbol of a ship’s helm on the lectern.] This symbol here is very fitting, because I think of our family as a ship. And our mother was the captain, making sure that the ship sailed as it should.

Yes, our mother was teacher. There were so many other lessons she wanted to instill in me, which I didn’t learn. I feel terrible about that. But what I have learned from her is a lot, and it is of great value. I think we could all apply the lessons from her example: her supportiveness, strength, confidence, and wisdom.

She was our mother. She was my best friend. She was my biggest fan. And now she is my conscience. Thank you very much.

I did not give the eulogy for my mother’s funeral. My cousin Wayne Nishioka did. But I did give the speech directly preceding his. Below is that speech. I did not have a written transcript but went by an outline. I rehearsed so many times, though, that I did memorize many sentences. This is the speech to the best of my recollection. I delivered it wearing my face mask.

Aloha. [Attendees saying “Aloha” back.] I want to thank all of you for being here. That includes those watching over Zoom.

Sunday, May 09, 2021

A Mother’s Day Message

Stuart K. Hayashi

I lost my mother on January 12 of this year. She deserves to be honored every day.

I lost my mother on January 12 of this year. She deserves to be honored every day.

Sunday, May 02, 2021

A Mothers’ Day Card I Should Have Drawn For My Mother When She Was Alive

Stuart K. Hayashi

Mom and Her Greeting Cards

My late mother put a huge emphasis on exchanging greeting cards every holiday. As I wrote on this blog before, I wasn’t a fan of this; it’s not as though the person giving the card drew the picture and wrote the contents. It seems my mother took that to heart. In later years, she often wrote a personalized note inside the card. When I neglected to get Mom a card for an occasion, my father would insistently buy one and demand I give it to her. Mom could always tell when I really did get her a card, as the ones I chose had cutesy imagery in them.

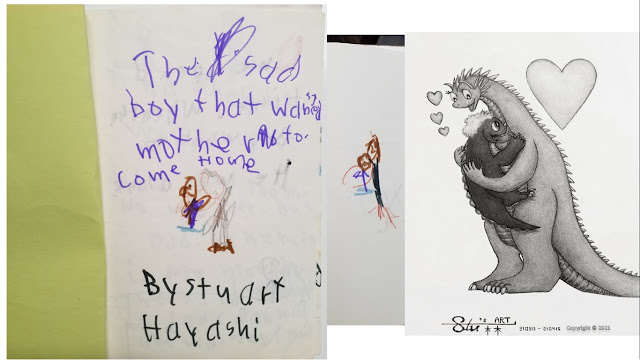

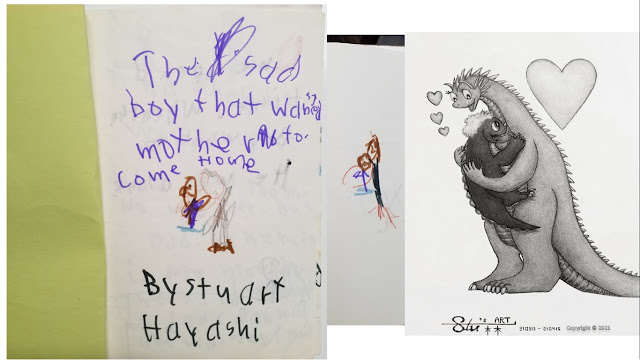

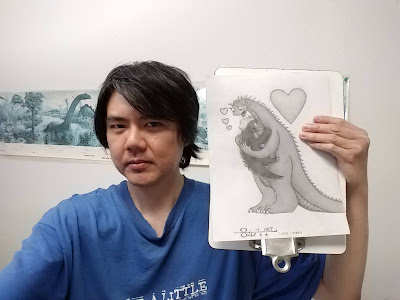

My mother never really understood my drawing dragons and monsters, even though, months before she died, I tried to explain the psychology of it to her. (I always felt like an outcast, but it didn’t make me feel weak. I felt rejected largely because of my imagination, which I considered powerful. A monster is a perfect symbol of an outcast feared for its power.) But Mom was still supportive of my art, and she did really like my cutesy drawings.

In 2010, I actually did draw my own Mothers’ Day card for Mom. Strangely, though, I took a character I normally draw in a cutesy fashion (the baby dragon in this particular drawing) and made him look a bit scary.

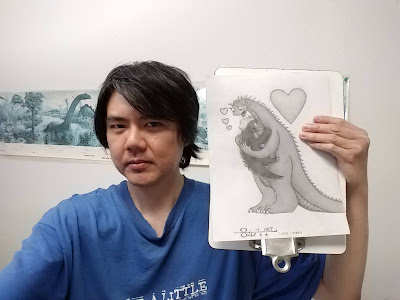

This dragon mom and her son I have rendered recently is the holiday card I should have given Mom. I feel guilty in that I could have drawn this for her any time in the past few years, even though the technique would have been much less sophisticated. It doesn’t console me to be told that Mom would have loved it. I am sure she would have, but that makes me feel all the guiltier for not having drawn this for her when she was alive.

Aside From My Not Having Been As Thoughtful As I Should Have Been, Other Reasons I Did Not Draw This Sooner

There were several factors working against my doing this drawing sooner, other than my not acting sufficiently on the knowledge that my mother’s time on earth was limited.

The first factor is that it was not until relatively recent that I had an idea of what I wanted a sufficiently cute and feminine “mother dragon” to look like and felt confident in drawing it. That was in March of 2019 when I did this drawing in attempt to impress another, much younger mother.

I’m also embarrassed to admit that I had not seen this drawing, I wouldn’t have thought of something as simple as the baby son dragon being cradled in his mom’s arms.

Conclusion

When it comes to my failure to draw and give this card to mom in her lifetime, there are only two thoughts that come close to consoling me. First is that Mom knew I was the sort of person who would want to pay tribute to her in this fashion, albeit my doing it much later than I should have. Secondly, I was frustrated in my mother’s final two months because she wanted me to help her attend to my disabled father. This took time away from my drawing. If my mom had to choose between my working on this holiday card for her versus helping her with Dad — which I did do — she would have chosen the latter. For her, the cards and my drawing this for her would be a great symbol of my love for her; my helping her with everyday activities, which she did see me do in the end, was a concrete demonstration of that love.

I started drawing this on paper on March 13, 2021. The paper version was “finished” on April 15. Thereafter, I worked on it in Microsoft Paint until April 22. I know that it will seem, at first glance to many people, to be something that is just for children. But, for me, it has a more personal meaning. It is the Mothers’ Day or birthday card that I should have drawn for my mother before she died on January 12 of this year.

Mom and Her Greeting Cards

My late mother put a huge emphasis on exchanging greeting cards every holiday. As I wrote on this blog before, I wasn’t a fan of this; it’s not as though the person giving the card drew the picture and wrote the contents. It seems my mother took that to heart. In later years, she often wrote a personalized note inside the card. When I neglected to get Mom a card for an occasion, my father would insistently buy one and demand I give it to her. Mom could always tell when I really did get her a card, as the ones I chose had cutesy imagery in them.

|

Aside From My Not Having Been As Thoughtful As I Should Have Been, Other Reasons I Did Not Draw This Sooner

There were several factors working against my doing this drawing sooner, other than my not acting sufficiently on the knowledge that my mother’s time on earth was limited.

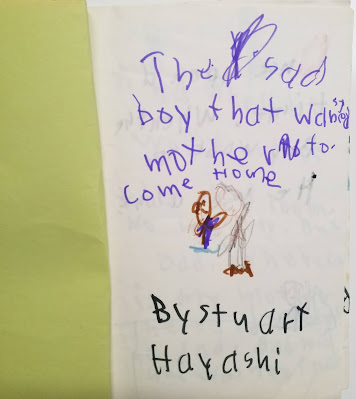

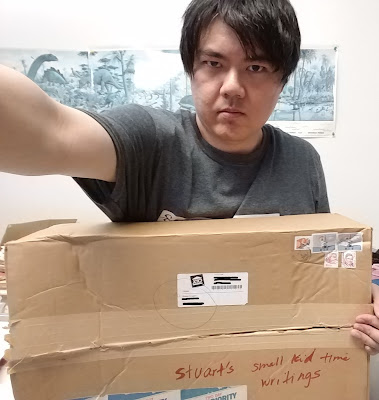

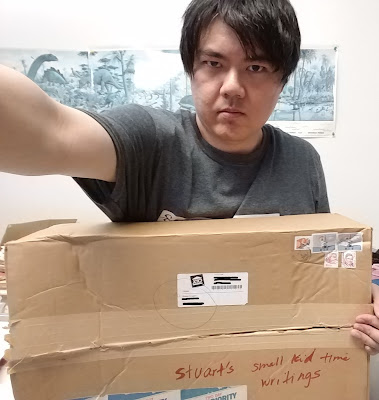

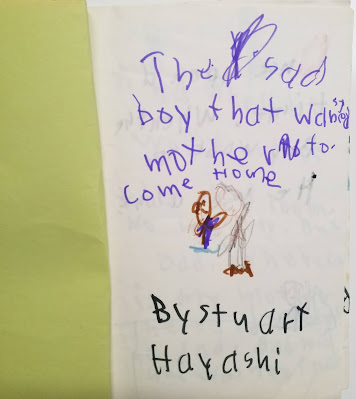

Then there is the second factor that worked against my doing this sooner. That factor is that this drawing was inspired by yet another one I did when I was six years old. I probably would not have done this drawing sooner had I not seen the older one. On a day without school, I woke up and was saddened that Mom was not home and would be gone day. I told Dad that I didn’t know what I would do without her. Since Dad knew of my already having the habit of drawing and writing my own picture books, he said, “How about ‘The Sad Boy That Wanted His Mother to Come Home’?” And that is exactly the book I made, down to the title.

The drawing style was what you would expect of a six-year-old. Both at the end and on the title page, upon the mother’s return home, the boy jumps into her arms. The mother- and son dragons’ positions in relation to one another, and their sizes in relation to one another, are based on the mother and son from my “The Sad Boy That Wanted Mother to Come Home.” I’m embarrassed to admit that I forgot about this particular drawing, and only remembered it as an indirect consequence of Mom’s death. Upon her death, I wanted comfort. Seeking it, I unearthed the box she put together of the picture books I made at age six — picture books I made with her encouragement.

Only then did I see the drawing of the boy in his mother’s arms.

Conclusion

When it comes to my failure to draw and give this card to mom in her lifetime, there are only two thoughts that come close to consoling me. First is that Mom knew I was the sort of person who would want to pay tribute to her in this fashion, albeit my doing it much later than I should have. Secondly, I was frustrated in my mother’s final two months because she wanted me to help her attend to my disabled father. This took time away from my drawing. If my mom had to choose between my working on this holiday card for her versus helping her with Dad — which I did do — she would have chosen the latter. For her, the cards and my drawing this for her would be a great symbol of my love for her; my helping her with everyday activities, which she did see me do in the end, was a concrete demonstration of that love.

Monday, April 05, 2021

Exposing the Fallacy of the Presumed Collective

Stuart K. Hayashi

This is a difference between how political individualism and political collectivism confront the issue of racial inequities. Imagine a specific white person subjected me to bodily harm. Then imagine I successfully sued that white person for damages. That would be political individualism, as the State would be taking individuals’ actions into consideration and accordingly holding them accountable. A specific individual harmed me, another specific individual, and therefore the individual aggressor had to recompense the individual victim.

By contrast, political collectivism does not bother to sort out individuals’ cases. Apparently, many advocates of political collectivism dismiss such specificity as being too complicated or cumbersome. Instead, in the aforementioned example, political collectivists blame white Americans in general for mistreating Asian-Americans in general. Hence, white Americans in general must pay taxes to Asian-Americans in general.

I know that advocates of race-based Social Justice will scoff at the above case study. As of this writing, I know of no legal initiative conducted in the name of Social Justice has gone as far as what I have described. The purpose of the above example is not to criticize activism in favor of race-based Social Justice. That is another controversy for another essay. The proposal described would definitely be an application of political collectivism. And I think that an extreme a case study stresses the important distinction between political individualism and political collectivism.

And this is not to say that it is necessarily collectivist if someone points out an observable and disturbing pattern of some white people often targeting Asian-Americans as objects of discrimination or abuse. To the degree that such a pattern occurs, calling attention to it can be in the service of protecting the specific individuals who are in danger.

Sometimes when political collectivism contrasts one group of people with another, a person’s individual choices do play a role in which group she ends up. To the degree that people are free to make their economic choices, they often do bear a lot of responsibility in whether they become rich or poor. Yet for political collectivists to pit the rich against the poor, or vice versa, is still a form of political collectivism.

Imagine a rich woman arbitrarily accused a poor man of a crime. Then imagine that law enforcement and the courts said, “Low-income people are usually less trustworthy than rich people. Therefore, we will just convict the low-income man.” That is still political collectivism. The reason is that the government’s decision is not based on the specifics of the case, but on the players’ respective memberships in contrasting groups. And those group memberships are not pertinent to what happened.

For much of my life, I thought it was rather obvious that descriptive (“metaphysical”) individualism and political individualism are correct, whereas descriptive social-collectivism and political collectivism are wrong. But, increasingly, I see and hear Social Justice activists take it for granted that their favorite forms of descriptive social-collectivism and political collectivism are beyond challenge or reproach.

A major reason why social collectivism — both the descriptive sort and the political implementation — is taken for granted, is that many Americans fall prey to a particular cognitive distortion or fallacy. It is one I call the Fallacy of the Presumed Collective.

Explaining the Fallacy of the Presumed Collective

In the essay, I will also explain how it is that we know that individualism, not social collectivism, is valid on the descriptive level. That is, it is a fact that the unit at which human decision-making is made is the individual person, not a larger group of which the individual person can be classified.

Many Billionaires Like the Estate Tax; Ergo, the Estate Tax Is Not Imposed on Any Billionaire Against His Will

Numerous issues of individualism versus collectivism in politics pertain to economics. Insofar as political-economic individualism is in effect, the State acknowledges that the wealth you receive peaceably as gifts or earned payments rightfully belongs to you. As a matter of course, the State should largely let you as an individual keep your wealth, even protecting it from forcible confiscation by anyone.

Conversely, political-economic collectivism states that the wealth you peaceably acquired is not yours alone, but is necessarily to be treated as something that must also be accessed by a larger group of people to which you are said to belong. That larger group is usually “the public” or “Society as a whole.” This collectivist policy will be in enforced regardless of whether you sought to avail those parts of your wealth to other members of this group.

The multi-billionaire Warren Buffet, one of the world’s richest men, promotes a political-economic collectivism of this sort. He avidly touts the virtues of the estate tax and of increasing other major taxes on billionaires and the USA’s wealthiest one percent. Of note is that Buffett maintains that these taxes are not some imposition that his fellow billionaires deserve. Rather, he professes, these taxes are no imposition at all.

Buffett fondly puts forth a particular insinuation. First, Buffett reminds us he is a billionaire. Second, Buffett informs us he highly approves of the estate tax. Moreover, he gathers together swaths of other billionaires who share in that approval. The implication is usually that billionaires, in general, approve of the estate tax. Therefore, we are to conclude, the estate tax is not some coercive measure that brutally extracts anything from anyone against her will.

“Frankly,” Buffett told a packed audience, “I think Bill [Gates] and I should have a higher tax rate on the income we get.” Gates, sitting next to him, agreed, “I go along with that wholeheartedly.”

Over the past few years, Mark Zuckerberg got into a bit of a verbal skirmish with Sen. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez about whether his taxes should be raised. But when he sat with President Obama in 2011, Zuckerberg agreed with Buffett’s line. Obama told him he wanted a change in the tax code that “allows for people like me and, frankly, you, Mark, to pay a little more in taxes.” To that, Zuckerberg replied, “I’m cool with that.”

From 2001 to 2012, Warren Buffett and other billionaires signed petitions and sent out press releases urging higher taxes on business moguls such as themselves. One of those signers, an heiress to Walt Disney’s fortune, proclaimed, “I can afford to pay the estate tax, and I should.”

Press coverage spelled out the implication that because billionaires do not mind the estate tax, it is not some inhumane constraint being placed upon them. A CNN piece put it, “A group of wealthy Americans, a former president and two Clinton-era Cabinet members called on Congress Tuesday to pass a much stronger estate tax.” That piece’s title was “Super-Wealthy: Tax Us More, Please.” As stated in a New York Times op-ed under Buffett’s own byline, “...the mega-rich...wouldn’t mind being told to pay more in taxes as well, particularly when so many of their fellow citizens are truly suffering.”

Here is what is missing from Buffett’s insinuations and implications. Each billionaire is an individual. They do not have to all agree. Warren Buffett can proclaim that he consents to paying more money to the federal government. If that is sincere, he can simply go to the website Pay.Gov and make a donation. The website even lets donors specify the federal agency to which they wish to direct their funds. By contrast, another billionaire named Charles Koch does not consent to paying more money to the federal government. When Buffett says he, as a billionaire, consents to billionaires being forced to pay more in taxes, the implication is that he speaks for billionaires in general. In truth, he does not. It is Buffett presuming to speak on behalf of other individuals.

Here is how Buffett’s argument falls prey to the Fallacy of the Presumed Collective in the more complicated manner I described. Buffett’s argument presumes that he and other billionaires are all the same unit, “billionaires in general”. Buffett conflates himself, as an individual, with other billionaires as if they are all a collective unit. That is, Buffett presumes that social collectivism is veritable on the descriptive level.

Presuming as much, Buffett and Gates and Zuckerberg then imply that because they desire higher taxes, it follows that billionaires, as a collective unit, desire higher taxes. They take the validity of social collectivism on the descriptive level as a given, In so doing, they prescribe that this social collectivism be implemented in political economy. This remains a fallacious asseveration, as Buffett has not bothered to elaborate how billionaires are a collective unit. That is just question-begging on his part.

To the extent that Buffett and his cohorts acknowledge at all that there are billionaires who disagree with them, those billionaires are quickly dismissed as lacking in any moral authority on this issue. Buffett and his cohorts are presented as the true representatives acting on behalf of the entire collective unit of billionaires. It is as though Buffett and his cohorts are the only members of this group who have a moral say when this issue is debated.

There is another example of this, and it is similar to Buffett’s argument. It has been one of the most popular arguments in political philosophy for over a century. It is the invocation of a Social Contract to argue for expansive government. Thomas Hobbes made this argument before Jean-Jacques Rousseau did. But many of the more complex side-arguments in defense of this wider argument can be attributed more directly to Rousseau.

Social Contracts and the Collective of Voting Citizens in a Democracy

I have written previously of the fallacies of citing a Social Contract to rationalize the expansion of government power over the peaceful activities of private individuals. But here I will specify the version of the argument that relies upon the Fallacy of the Presumed Collective.

When that Fallacy creeps into the Social Contract gambit, this is how it presents itself.

To translate, if elected officials craft and enforce laws that constrain your ability to access a gun for self-defense, that is not really an abrogation that defies your authorization. You remain within the true decision-making unit, which is the collective of voting citizens. The collective of voting citizens democratically resolved to install the officials currently elected. This collective of voters delegated, to these representatives, the rightful authority to issue directives that hinder your ability to access a firearm. And you are among this collective that ratified this gun control. Ergo, you ultimately ratified this gun control. This posited “collective choice” is normally labeled the general will.

Accordingly, U.S. Sen. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez advances an assertion similar to Obama’s. “[...I]n a democracy, the government is us. ...the government is The Public, and The Public decides what is good for itself.”

Yes, we hear these platitudes offered to rationalize the sophism that the actual unit of political decision-making is some collective that is the voting majority. The fact remains that in our actual, everyday lives, we are still individuals. It is as an individual that you make your life choices. Insofar as the outcome of democratic votes can override the ability of a legally-competent adult to opt to do anything that is peaceful, these democratic votes amount to voting majorities imposing their will on voting minorities and on nonvoters.

Imagine you are childless and do not vote. Perhaps you have refrained from voting. Perhaps you are a resident alien who has not yet obtained citizenship. Suppose that, as a result of a democratic vote, your township criminalizes any inhalation of marijuana. Yet, in the privacy of your own home, you smoke a joint. Then imagine that armed police officers invade your home to arrest you, per the democratically crafted law.

Your action was not the result of some collective choice — an oxymoron — on the part of voters in the township. On the descriptive level, there is no “general will.” What contemplated and then executed the choice was the actual unit of decision-making: you, the individual. An individual decides what is good for herself. And, contrary to Sen. Ocasio-Cortez’s equivocation, a collective “Public” does not decide “what is good for itself.”

When the police arrive to bust you, apologists for Rousseau’s interpretation of the Social Contract can issue their favorite rationalization. They will say that the State is simply holding you to a rule to which you voluntarily assented. They add that this applies even if you assented to this rule by the most indirect means.

What actually happened was something different. As with Warren Buffett’s apologia for raising taxes, it was this. Some individuals (Group A) used the armed force of government to enact control over other individuals (Group B). Then members of Group A deny this was an actual imposition. They do so by eliding any distinction between Groups A and B. Rather, they imply, there is no relevant distinction between Groups A and B in this context. As far as they are concerned, all members of both groups are part of a larger unit, Collective C. And Collective C is an autonomous unit that makes decisions for itself. Hence Sen. Ocasio-Cortez’s equivocation that “the government is The Public, and The Public decides what is good for itself.”

In this instance, Collective C has resolved for itself that the smoking of marijuana would be criminally punished by the State. Therefore, when the State penalizes you for consuming cannabis, it doesn’t matter that you personally object to such a decree. Your court sentence is simply an instance of the General Will holding true to its own rules that it set for itself.

In the controversy over Warren Buffett and higher taxes on the rich, Group A consists of billionaires supporting such tax hikes. Group B is of billionaires who oppose these tax hikes. Warren Buffett and the favorable press he received in this campaign have been, at best, vague about such a distinction between such groups. Rather, members of Groups A and B are lumped together in Collective C, “billionaires in general.” And Warren Buffett and his allies in the media frame the controversy as though Collective C has elected for itself that Collective C wishes to transfer more of its riches to the federal government.

And no, on the topic of Social Contracts, it is not true that a national government’s taxes and other impositions are rendered voluntary by the fact that “You can leave any time you want!” As I have written priorly, the USA and other First-World governments charge you money should you relinquish your citizenship. That is one last ransom for you to pay.

“You Didn’t Build That”

Such a miserly entrepreneur, is it believed, is being petulant. Who is she to yelp that because she earned her fortune, it is wrong for the State to encroach on her right to keep it and control every last penny of it?

These self-made entrepreneurs, say Obama and Warren, are deluding themselves and others. Obama and Warren proclaim that the entrepreneurs’ conviction falls apart on account of the entrepreneurs overlooking an essential consideration. That consideration is that achieving success likely would not have been possible if the entrepreneur had not received help from other people. Upon reflecting on that, we are to conclude that the entrepreneur’s success should not be attributed to her choices as an individual. On the contrary, her success was the result of a collective achievement by society as a whole. To take the Obama/Warren argument to its logical conclusion is to profess that great productive achievements should be credited to everyone in general and nobody in particular.

As Elizabeth Warren says it,

Individualism Vs. Collectivism, Both on the Descriptive Level and the Political (Prescriptive) Level

Individualism on the descriptive level is the recognition that each legally-competent human being is an individual with his or her own will, consciousness, and capacity for decision-making. This descriptive level is what admirers of Ayn Rand’s Objectivist philosophy call “the metaphysical level.”

Accordingly, there is also the idea of individualism as applied prescriptively to politics. Individualism, applied politically, means that every legally-competent adult human being must be recognized as an individual with a right to bodily autonomy. This entails that if I see another legally-competent adult showing eating habits that I judge will be bad for him in the coming decades, it would be wrong for me to try to use the power of government to override his choices. Recall, as I have explained before, that laws are ultimately enforced by armed men exerting their will upon the lawbreaker.

In contrast to the idea of individualism is social collectivism. To agree that collectivism is correct on the descriptive (“metaphysical”) level is to believe that the actual unit of decision-making among human beings is not the individual person. No, says collectivism, the true unit of decision-making is some larger group of which this person may be a member. Often, continues this notion, the group that makes someone’s choices is a group in which that person did not even choose to belong.

An example of such collectivism would be the belief that an entire ethnic group or race, as a whole, can make choices for all or most of its members. One application of this interpretation is as follows: I am of Japanese ancestry, and I have an interest in the sciences, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). That is consistent with stereotypes about persons of Japanese ancestry. To apply descriptive-level social collectivism to this context would be to assume that my interest in STEM has less to do with my own uniqueness as an individual than it does my membership in a collective group that is often associated with STEM.

“The descriptive level,” here, refers to judgments that are presented as truthful or factual. Descriptive is that which “is.” Also of note is the prescriptive level. That which is prescriptive refers to what ought to be done.

Social collectivism is also advocated on the prescriptive level. That is ethical collectivism, which proclaims that a supposed collective, not any one individual, should have first priority in being the main beneficiary of someone’s actions. When it comes to priorities, this usually calls for the individual to subordinate her own well-being to that of some group of people as a whole. This prescription applied to the functions of government is known as political collectivism. Political collectivism has the State enforce the prioritization of some supposed social collective above the individual. This can manifest in at least one of these two policies.

Ethnicity-based policies are one type of implementation of political collectivism. Many people observe that, for the past 150 years, a large number of white Americans have violently mistreated Americans of Asian descent. That is true. Yet some social activists would conclude from that observation that white American in general happen to impose violent mistreatment toward Asian-Americans in general. And that is a much shakier conclusion.

Individualism on the descriptive level is the recognition that each legally-competent human being is an individual with his or her own will, consciousness, and capacity for decision-making. This descriptive level is what admirers of Ayn Rand’s Objectivist philosophy call “the metaphysical level.”

- Sacrifice of the well-being of an individual for the ostensive benefit of a group to which she belongs. That group is usually “Society” or the political jurisdiction.

- Sacrifice of the well-being of members of one group to that of another group.

This is a difference between how political individualism and political collectivism confront the issue of racial inequities. Imagine a specific white person subjected me to bodily harm. Then imagine I successfully sued that white person for damages. That would be political individualism, as the State would be taking individuals’ actions into consideration and accordingly holding them accountable. A specific individual harmed me, another specific individual, and therefore the individual aggressor had to recompense the individual victim.

The ethical problem is how that imposes injustice on specific individuals. Individual white Americans who have not committed violence against Asian-Americans are vilified and punished as oppressors anyway. As a corollary, specific Asian-Americans (in this instance, me), who have not been directly brutalized by whites in general, will be paid this tax money as a reparation for something that was not actually inflicted upon them.

Explaining the Fallacy of the Presumed Collective

This is the Fallacy of the Presumed Collective. Person X argues in favor of social collectivism over individualism. To argue this, Person X offers what she considers to be proof of her correctness. But her argument actually relies upon her presuming, from the outset, that social collectivism has already been validated.

This can be described in more complicated and specific terms. On the prescriptive level, Person X wants the enactment of a public policy that is in line with political collectivism. Person X thus advances some argument in favor of political collectivism. But this argument already presumes, from inception, that social collectivism on the descriptive level is indisputable or has already been vindicated. That is a fallacious presumption. As I will explain in this essay’s final section, social collectivism on the descriptive level is demonstrably false.

The Fallacy of the Presumed Collective is a combination of two other logical fallacies. The first is “Begging the Question” or “circular reasoning.” In this fallacy, an argument that purports to prove Y itself presupposes Y already being accepted as true. An example of this would be my saying that everything that Book Q says about biology is factually correct because Book Q itself says everything in Book Q about biology is factually correct. That is bunk, as you would need sources of information on biology other than Book Q — the more direct the evidence, the more reliable — to corroborate Book Q’s veracity.

And there is the second fallacy that is found in the Fallacy of the Presumed Collective. That second is called the Composition Fallacy. The Composition Fallacy presumes that if a statement about part of R is true, then it follows that the statement applies to R as a whole. It is true, for instance, that automobiles have parts that are glass. It would be the Composition Fallacy, though, to conclude from this that the entire automobile consists of glass.

Pernicious stereotypes are a form of the Composition Fallacy being applied to categories of human beings. Many persons of Asian descent, for example, are violent criminals. It would be an especially hazardous form of the Composition Fallacy to conclude that this means that Asian-descended persons, in general, are violent criminals. (I thank Raymond C. Niles for introducing me to the concept of the Composition Fallacy.)

I will provide four case studies of well-known public commentators asserting influential arguments that ultimately fall prey to the Fallacy of the Presumed Collective. I think all four case studies imperil the principle of individual rights, though the last one stands out as the most noxious. These four cases are:

- If I “consent” to this, everyone in my demographic group consents to it.

- The Jean-Jacques Rousseau-influenced Social Contract argument (related to 1).

- “You Didn’t Build That.”

- The White Nationalists’ rationalization for imposing political collectivism based on ethnicity.

Many Billionaires Like the Estate Tax; Ergo, the Estate Tax Is Not Imposed on Any Billionaire Against His Will

Numerous issues of individualism versus collectivism in politics pertain to economics. Insofar as political-economic individualism is in effect, the State acknowledges that the wealth you receive peaceably as gifts or earned payments rightfully belongs to you. As a matter of course, the State should largely let you as an individual keep your wealth, even protecting it from forcible confiscation by anyone.

Social Contracts and the Collective of Voting Citizens in a Democracy

I have written previously of the fallacies of citing a Social Contract to rationalize the expansion of government power over the peaceful activities of private individuals. But here I will specify the version of the argument that relies upon the Fallacy of the Presumed Collective.

You balk at such governmental imposition made upon you in the First World. But because you are a citizen of the First World, you actually live under a democratic representative government. Under such a representative democracy, the people vote on such measures. Either they do so directly by ballot initiative or they do so indirectly by electing representatives who craft the legislation.President Obama gladly presents a variant of this nostrum. He remarked that he was nauseated by constituents who wail, “I need a gun to protect myself from the government.” To those who voiced concern that he and likeminded politicians were making impositions on them in opposition to their will, he replied that “the government is us. These officials are elected by you. . . . I am elected by you. . . . It’s a government of and by and for the people” (emphases Obama’s)Therefore, as a voter or citizen, you ultimately consent to every statute your government enacts. This applies even when you vehemently detest the statute as is interpreted or enforced. And this renders disobedience of such statutes to be puerile at best.

“You Didn’t Build That”

We [beings] know no time when we were not as now: self-begot, self-raised by our own quick’ning power.—Lucifer in Milton’s Paradise Lost,

Bk. 5, lines 859–860

...the heresy which is at the root of his whole predicament — the doctrine that he is a self-existent being, not a derived being...President Obama and U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren invoked a similar version of this Presumed Collective fallacy in a more well-known controversy. Obama and Warren derided self-made entrepreneurs. These self-made entrepreneurs, it is said, believe their fortunes to be nothing more than the culmination of their own hard work and wise choices. As a result, it is said, these self-made entrepreneurs bristle at any call for higher taxes or increased governmental regulation of their business.—C. S. Lewis, “A Preface to Paradise Lost”

(The original “You Didn’t Build That”)

There is nobody in this country who got rich on his own — nobody. . . . Now, look, you built a factory and it turned into something terrific or a great idea. God bless — keep a big hunk of it. But part of the underlying Social Contract is you take a hunk of that and pay forward for the next kid who comes along.And as President Obama phrased it more famously,

...if you’ve been successful, you didn’t get there on your own. . . . I’m always struck by people who think, ‘Well, it must be because I was just so smart. . . . It must be because I worked harder than everybody else. ...’ ...If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. . . . If you’ve got a business — you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen. . . .

...there are some things we do better together. . . . We rise or fall together as one nation and as one people . . . You’re not on your own; we’re in this together. . . .

[Responsible Americans have] understood that...succeeding in America wasn't about how much money was in your bank account, but it was about whether you were doing right by your people, doing right by your family, doing right by your neighborhood, doing right by your community, doing right by your country...

New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristoff adds,

The reasons for this, which the arguments of Warren and Obama have conveniently ignored and obscured, are as follows. First, human beings are individuals. The fact has a corollary. That corollary is that, to the degree that people have cooperated peacefully on these projects, each individual’s contribution can be identified. Upon being identified, the size of each individual’s contribution can be measured, sometimes even quantified. That is the whole point behind documentation that establishes your “financial identity.” Throughout this section of the essay, we shall discuss how the recognition of your financial identity happens to undermine the political collectivism foisted in “You Didn’t Build That.”

Because People Are Individuals, the Entrepreneur Already Identified the Help She Received and Paid for It

Entrepreneurs have indeed received help from other individuals. But insofar as they have gone about matters peacefully, the entrepreneurs have already identified the help from those other individuals and compensated them for it.

For over a century, students have conventionally been taught that the three major factors of production are manual labor, factory equipment and other tools, and natural raw materials. Conventionally omitted was the fourth and most important factor of production: the management and planning of the entrepreneur. The entrepreneur, devising the plans and overseeing their execution, must provide proper instruction to the manual laborers. That instruction is on how the manual laborers are to use the factory equipment and other tools to convert the natural raw materials into the finished product.

Let us imagine what would happen if all factors of production were present, except for the entrepreneur’s management. The manual laborers would not receive adequate instruction on what to do with the natural raw materials and the factory equipment and tools. The manual labor would go to waste. The factory equipment and tools would sit idle. The natural raw materials would not be converted into the useful products. Nothing would get done. That is part of the premise of Ayn Rand’s novel Atlas Shrugged.

“Ah,” one might ask, “But what if a manual laborer took charge to formulate plans and convey practical instruction to the other laborers?” That laborer that has taken this leadership position would now be filling the role of the entrepreneur. There is no proper leadership for manual laborers in the production process without entrepreneurship or executive management.

The manual labor, the natural raw materials, and the factory equipment are all expenses for which the entrepreneur must pay. Suppose the entrepreneur charges customers $10 per unit. For every unit sold, four of those ten dollars goes to remunerating the first line of creditors to whom she owes money: the employees. Three of the dollars go to paying for the natural raw materials. Two of the dollars go to pay for the factory equipment and other tools. What is the one-dollar profit left over for the entrepreneur herself? That is the customer’s payment directly to the entrepreneur for the service she provided. The service was the entrepreneur employing her managerial decision-making to manage the manual labor, natural raw materials, and factory equipment to produce a product useful to the customer.

To the degree that employer and employee are free to negotiate compensation rates, the employees’ compensation was the result of mutual agreement between the employer and they. Any time someone is offended by a large disparity between the wealth of the entrepreneur versus the compensation of her employees, it is stated that she is being chintzy with her employees. We hear screaming that she should “give back” to them.

Who built this country? Entrepreneurs, yes. But so did schoolteachers and railway construction workers. Doctors and truckers. Scientists and soldiers. You didn’t build it, . . . — we all built it.Granted, almost every successful entrepreneur in history has received some sort of help from someone else. But the arguments of Warren and Obama are knocking down a straw man. Hardly any free-market advocate says that every successful entrepreneur or inventor built a fortune ex nihilo. Moreover, the entrepreneur is right that she should be able to keep the fruit of her work. She is right that insofar as she is nonviolent and violates no one else’s rights, she should not have her property confiscated or micromanaged by the State.

Because People Are Individuals, the Entrepreneur Already Identified the Help She Received and Paid for It

Entrepreneurs have indeed received help from other individuals. But insofar as they have gone about matters peacefully, the entrepreneurs have already identified the help from those other individuals and compensated them for it.

True, there are instances where employees may have underestimated their own leverage when it comes to being able to bargain for higher compensation. In those instances, they would be right to attempt a renegotiation. But insofar as the market is free, the entrepreneur has already paid her employees what their jobs are worth.

Yes, every entrepreneur did obtain assistance from others. But once that entrepreneur paid off her expenses, that entrepreneur does not continue to be indebted to those who helped her. Those who helped her directly have already been paid for their contribution. We know this because of documentation of each employee’s financial identity. The document in particular is the entrepreneur’s payroll. The profit the entrepreneur has left over is rightfully hers. That is her customer’s direct payment for her own unique, rationally identifiable and measurable contribution that came from her choices as an individual. Hence, the right of the entrepreneur to keep and control her profits is not contingent on her having done everything alone.

What About Taxpayer-Funded Public Goods?

Yet, continue Obama and Elizabeth Warren, entrepreneurs are also ingrates when it comes to paying taxes to fund government-controlled services. These services include road maintenance and education.

Elizabeth Warren goes on, “You built a factory out there? Good for you. But I want to be clear. You moved your goods to market on the roads the rest of us paid for. You hired workers the rest of us paid to educate.”

Obama, too, says, “Somebody invested in roads and bridges.”

Though it is difficult to make a precise quantified measurement of such a benefit, it is safe to concede that entrepreneurs do benefit from such taxpayer-funded services. But the existence of such a benefit to entrepreneurs is not, as Obama-Warren-Kristof assume, an argument for more taxation on the rich and for more government control over utilities such as roads.

I have written on this topic earlier. The assumption is that if we are accustomed to receiving a particular service from a taxpayer-funded government agency, such as road maintenance, that service would never have existed if not for it having been created by a government agency.

The reality is that in the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was private entrepreneurs who first provided roads. Merchants whose shops adjoined one another along the same street would pool their resources to fund the construction and upkeep of a privately-owned turnpike. The turnpike was owned and maintained by a private company, and this private company was jointly owned by the merchants whose land adjoined the road. The private turnpike company itself seldom made a profit exceeding two percent. However, everything else being equal, the presence of the roads did increase the profit margins of the merchants’ shops by a much greater degree.

These private turnpikes were so successful that they were able to connect entire cities to one another. Such a private, for-profit toll road connected Philadelphia to Lancaster. Economic historians Herman Krooss and Charles Gilbert note, “By the 1820s, all the major cities in the United States had been connected by [private] toll roads...” It was even a private entrepreneur, Carl G. Fisher, who raised funds consensually for the construction and maintenance of the USA’s first interstate highway.

Such private, for-profit roads fell into disuse when the merchants who were funding them had fallen prey to a political collectivism comparable to Obama’s and Warren’s. These merchants surmised that they could drive down their own costs further still if their local governments decided to tax everyone, in general, for the construction and maintenance of roads that led patrons to their shops.

In the same “You Didn’t Build That” speech, Obama talked about how entrepreneurs benefit from firefighting services. As with roads, Obama presumed that absent of a taxpayer-funded government agency, there would be no adequate firefighting service. He chastised, “I mean, imagine if everybody had their own fire service. That would be a hard way to organize fighting fires.”

But as I have written here, it was private entrepreneurs who first provided adequate firefighting as well.

To the degree that entrepreneurs do unfairly benefit from taxpayer-funding of government services, it is that Private Individuals A and B are being forcibly taxed to benefit Entrepreneur C. And it is unfair if Private Individuals A and B do not themselves benefit directly. But, contrary to Obama and Elizabeth Warren, that is not an argument to tax or regulate Entrepreneur C further. Rather, it is an argument that the taxes be returned to Private Individuals A and B. It is also an argument that whatever service that is funded by tax collection should be a service that is performed by the private sector.

Insofar as Entrepreneur C is advantaged from taxpayer funding of road construction or upkeep, the size of that advantage gained is difficult to measure precisely. Insofar as the roads are owned and maintained by a private owner in a free market, it is easier for Entrepreneur C to identify the specific parties whose services benefit her. She can seek out those specific parties and contract with them accordingly. Note that the result is not an increase in political-economic collectivism but in political-economic individualism.

The political-economic collectivism of government ownership of roads, firefighting, and other services does nothing better than the following. We know that some parties put more money into public coffers than they remove. That is Category 1. There are also parties that consume more resources from public coffers than they put in. That is Category 2. Political-economic collectivist government ownership of resources obscures who is in Category 1 and who is in Category 2. It all remains nebulous.

How Individual Financial-Identity Identifies What and How Much One Individual Owes Another, and How Political Collectivism Obfuscates This

I fear that this nebulousness is something that advocates of government control may consider to be a plus instead of a minus. Of concern here is what I touched upon earlier, and which I have discussed in other essays: your financial identity.

Once again, your financial identity refers to documentation that identifies your creative actions in the economic sphere. Such documentation allows for parties indebted to you to identify you. Upon doing so, they can send you the exact payment to which you both agreed when you provided your service to them. Acknowledging individualism, what one specific individual owes to another is accurately identified.

Identity theft refers to the deliberate obscuring of your financial identity. An identify thief can impersonate you and thus collect money that debtors, such as your employer, owe to you. By obscuring the distinction between you versus he, the identity thief forcibly redistributes wealth. He takes the value that you created, and claims it for himself.

A similar obscurantism occurs with the “You Didn’t Build That” mentality. When roads are privately owned and funded, the customers who most directly benefit from a road are likewise the parties that most directly fund it. Again, what one specific individual owes to another is identified properly. The same applies to the free contracting between employer and employee.

But “You Didn’t Build That” obscures the sizes of specific contributions by specific individuals to specific creative enterprises. By pretending that individual achievement is always collective achievement, the contribution of each individual becomes murky. By obscuring the distinction between those who are net contributors to an enterprise or coffer versus those who take more than they contribute, this political-economic collectivism redistributes wealth. It allows for net-takers to take the value that the net-givers created, and claim it for themselves.

Hence, the details identifying who-contributed-what fall under a cloak. The cloak is the idea that every productive achievement came from everyone in general and no one special person in particular.

Political-economic individualism and consistently applied privatization hold individuals accountable for their own chosen actions. They are held especially accountable for their economic choices. None of that precludes people from relieving sufferers of misfortune through consensually provided and consensually funded charity. By contrast, pretending that there are not individuals but vague collectives allows individuals to escape accountability for their own poor choices. Worse, it belittles the credit owed to individuals for their wisest commitments.

Once again, the argument that allegedly proves the case of Obama and Warren hinges on the premise that social collectivism, on the descriptive level, is already a given. The descriptive-level social collectivist premise is that we should simply accept that no great achievement can rightfully be attributed to a specific individual. Rather, every great achievement is the culmination of imprecisely defined contributions from society’s members in general.

Many commentators disgusted by the “You Didn’t Build That” speeches did not go far enough in denouncing them. These critics at least implicitly understood that the speeches obfuscated the fact that it’s possible to identify each contributor to a creative enterprise and the size of her contribution. Consequently, these critics noticed that the speeches obscured the distinction between one contribution and another in order to rationalize the confiscation of the wealth of every creative enterprise’s leader: its entrepreneur. But it is worse than that.

What About Taxpayer-Funded Public Goods?

Yet, continue Obama and Elizabeth Warren, entrepreneurs are also ingrates when it comes to paying taxes to fund government-controlled services. These services include road maintenance and education.

How Individual Financial-Identity Identifies What and How Much One Individual Owes Another, and How Political Collectivism Obfuscates This

I fear that this nebulousness is something that advocates of government control may consider to be a plus instead of a minus. Of concern here is what I touched upon earlier, and which I have discussed in other essays: your financial identity.

Although millions or billions of people can opt for joint ownership in a single corporate asset, it goes noticed that capitalism is individualistic by its nature. The institution of private property follows from the fact that a particular quantity of