The Longest Version

INTRODUCTION

PART ONE: OVER 17 PROFILES OF LIFESAVING FOR-PROFIT ENTERPRISES

* Creativity in the Age of COVID – Makers of the COVID Vaccine

* Patrick and Paclitaxel – Patrick Soon-Shiong and His Cancer Drug

* The German From Genentech – Axel Ullrich and His Biotech Cancer Treatment

* Hooray for Herbert – Herbert Boyer, David Goeddel, and Genetically Engineered Insulin

* The Creation of CRISPR – Jennifer Doudna, George Yancopoulos, and Gene Editing

* Dr. Profit – Paul Offit and the Rotavirus Vaccine

* Men Against Meningitis – David Hamilton Smith and His Vaccine for Meningitis

* Capitalism Does Have a Heart – Wilson Greatbatch, C. Walton Lillehei, and Implantable Pacemakers

* What Can Be Scanned – Raymond Damadian and MRI

* Bravo for Baekeland – Leo Baekeland and Plastics in Hospitals

* Enemy of Arthritis – Percy Julian, Sr., and New Foam for Fire Extinguishers

* Duane and His Detector – Duane Pearsall and Smoke Detectors

* Excellent Electricity – Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, the Air Brake, and Electric Heating

* Glorious Gail – Gail Borden and Condensed Milk

* Thomas Midgley, Now Depicted As Evil, “Has Saved Millions of Lives” – Thomas Midgley and Air Conditioners

* “Death Ray”? More Like “Life Ray” – Gordon Gould and the Laser

*Fritz and His Fertilizer – Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and Synthetic Nitrogen Fertilizer

PART TWO: HOW, CUMULATIVELY, BILLIONAIRES SAVE BILLIONS OF LIVES

* Value Added to Natural Resources

* Natural Fact One (of Two): Resource Substitution

* Natural Fact Two (of Two): Greater Utility From Fewer and Smaller Inputs

* The Carrying Capacity of Land

* Improved Productivity Helps People on the Lower Income Distribution

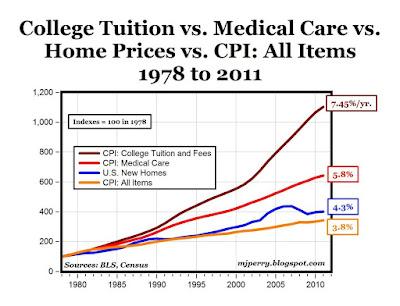

* Goods That Have Not Decreased in Real Price

* The Poor Get Richer

* What Capitalism Can Do for the Climate

* Capitalism Vs. Hunter-Gatherer Life Vs. Socialism

* Capitalism Vs. Taxpayer Funding for Basic Research and R-and-D

CONCLUSION

INTRODUCTION | ^

America’s billionaires are rich in their finances and poor in reputation. They have not been getting good press lately.

For much of the past few decades, the common attitude in America was that it is morally permissible to become a billionaire as long as one “gives back” in the form of philanthropy. That was the attitude formalized in The Gospel of Wealth penned by the richest man of its day, Andrew Carnegie. But over the past several years, the debate has shifted to whether it should be legal for any entrepreneur to become a billionaire at all.

Heralding this change was a January 2019 interview that left-wing writer Ta-Nehisi Coates conducted with then-freshman U.S. Sen. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. “Do we live in a moral world [if it is one] that allows for billionaires?” Coates asked her. “Is that a moral outcome?”

“No, it is not,” she replied. For this, she received uproarious cheers and applause.

She went on, “I do think a system that allows billionaires to exist — when there are parts of Alabama where people are still getting ringworm because they don’t have access to public health — is wrong.” Here she insinuates that an entrepreneur possessing billions of dollars’ worth of wealth somehow contributes to those Alabamans being too poor to receive adequate protection from, and treatment for, ringworm.

Sen. Ocasio-Cortez’s answer made headlines. It became apparent that many people in the United States and other countries agreed wholeheartedly with it. Almost as famously as his boss, AOC’s policy advisor and senior counsel Dan Riffle was quoted throughout the media proclaiming, “Every billionaire is a policy failure.”

Still more notorious than AOC is a man with seniority over her in the U.S. Senate, Bernie Sanders of Vermont. “There is something profoundly wrong,” he shouted in his announcement for his 2016 presidential run, “when in recent years, we have seen a proliferation of millionaires and billionaires [actually, ‘MILLIONAYAZ AND BILLIONAYAZ’] at the same time as millions of Americans are working longer hours for lower wages and we have shamefully the highest rate of childhood poverty of any major country.”

Note the implication here — as with Sen. Ocasio-Cortez — that the “lower wages” and “child poverty” are at least partially caused by this “proliferation of millionayaz and billionayaz.”

That billionaire entrepreneurs have such an unflattering image can be seen even in attempts to compliment them. Such can be gleaned a video essay by pop-culture commentator Lindsay Ellis. Despite her overall sympathies for the anti-capitalist message of the computer-animated movie adaptation of Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax, she found herself vicariously embarrassed that it was presented in such a ham-fisted manner. In a gesture of perfunctory evenhandedness, Ellis states what she apparently considers to be the strongest argument in favor of for-profit commerce: “...corporations employ people and make us stuff — maybe not necessary stuff, but stuff.”

The triteness of her evaluation would not be so concerning, except that it seems even many of the most prominent “defenders” of free enterprise tacitly agree with this characterization. The best that can be said of market economics, it is believed, is that businesses “make us stuff,’ stuff that is “not necessary.” The run-of-the-mill defense of capitalism is that it incentivizes the production of “stuff” much more effectively than do the State-owned enterprises of socialism. Socialism might manufacture not-necessary stuff, but capitalism elicits much more competence in the assembly of not-necessary stuff!

And as entrepreneurs become billionaires by hawking this not-necessary stuff, we are told, these same entrepreneurs add to “child poverty” and Alabamans “still getting ringworm” by hoarding all the wealth and resources for themselves.

As Ocasio-Cortez added in 2020, the billionaires “made that money off the backs of single mothers, and all these people who are literally dying because they can’t afford to live.”

Human beings are “literally dying” for the reason that billionaires “made that money”? It is no wonder their legacy is tarnished.

Yet there is more to this story. Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci — the scientific married couple who cofounded BioNTech of Germany — became billionaires from developing the first existing COVID-19 vaccine. Noticing this, entrepreneur Louis Anslow tweeted out a Time magazine cover featuring these two, and asked in his tweet, “Are you sure no one deserves to be a billionaire?”

Anslow’s is a worthwhile question. To explore it, this essay comes in two parts. Part One ascertains that there is indeed more that can be said for capitalism and entrepreneurial billionaires than that they “make us stuff.” That many of the free market’s putative advocates tacitly agree with Lindsay Ellis’s belittling of capitalism’s benefits can be inferred from what they have omitted from their “pro”-capitalism statements. What they refrain from stating plainly is that free enterprise — more than any other sort of political economy, socialist or otherwise — has provided the freedom and impetus for innovators to save, lengthen, and enhance human lives. Not just about making us “stuff,” capitalism saves lives. And that is the point that capitalism’s so-called proponents should be emphasizing. If capitalism’s lifesaving nature were obvious to most people, not even an ideologue such as Lindsay Ellis could have been so confident in stating, as a generally accepted platitude, that capitalism is all about producing “stuff” that is “not useful.”

Hence, Part One is a series of over seventeen case studies of this principle in action. Where they are available, the estimated number of lives that a for-profit enterprise saved shall be enclosed. Most of those case studies involve pharmaceuticals and medical devices, but there are other examples that are far less obvious. Electric heating, air conditioners, and even lasers save lives. It was capitalism that facilitated the invention, production, and adoption of these technologies.

To Part One, a detractor can reply, “Yes, that entrepreneurs produce medical devices is nice. But as the Earth consists of a fixed quantity of nonrenewable natural resources, it follows that one person owning a billion dollars’ worth of resources means there is less for everyone else. In that respect, if someone invents a life-saving medical device and gains a billion dollars from that, a billion dollars’ worth of resources all going into the possession of this one man still adds to other people’s poverty and the premature death that it brings.”

Such an assumption fails to understand the actual nature of wealth — economic value — and its origin. Consequently, Part Two considers the prospect that there is no inherent limit to the amount of economic value to benefit human beings. Further, insofar as citizens are free and peaceful with one another, someone gains ownership over a billion dollars’ worth of resources to the extent that she created economic value that was of at least that much worth to others. Part Two also summarizes how capitalism contributed to boosting living standards overall, sometimes even in the poorest countries where the government allows for relatively little capitalism. Whereas Part One focuses on specific inventor-entrepreneurs whose efforts have saved lives, Part Two ends with a summary of how peaceable commerce, in total, saves lives on an international scale.

With that, we take a journey into the past two centuries of entrepreneurship and its lifesaving.

The married couple of scientists, Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci, co-founded BioNTech in Germany and partook in a joint venture with the USA’s Pfizer to develop the USA’s first vaccine for COVID-19, one that is an mRNA vaccine. Various attempts have been made to attribute this success more to taxpayer funding than to the couple’s initiative. President Donald Trump tried to take credit for BioNTech’s achievement, proclaiming that it came from Operation Warp Speed, his administration’s program to provide federal funding to synthesize such a vaccine. Yet BioNTech and its American collaborator, Pfizer, did not receive money from this program.

Are you sure *no one* deserves to be a billionaire? pic.twitter.com/MYuSzH8TVf

— Louis Anslow (@LouisAnslow) July 27, 2021

PART ONE: OVER 17 PROFILES OF LIFESAVING FOR-PROFIT ENTERPRISES | ^

Creativity in the Age of COVID | ^The married couple of scientists, Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci, co-founded BioNTech in Germany and partook in a joint venture with the USA’s Pfizer to develop the USA’s first vaccine for COVID-19, one that is an mRNA vaccine. Various attempts have been made to attribute this success more to taxpayer funding than to the couple’s initiative. President Donald Trump tried to take credit for BioNTech’s achievement, proclaiming that it came from Operation Warp Speed, his administration’s program to provide federal funding to synthesize such a vaccine. Yet BioNTech and its American collaborator, Pfizer, did not receive money from this program.

I increasingly feel that the act of entrepreneurship and innovation is very much an act of immigration. Immigrants leave their comfort zone, expose themselves to the negativism in the face of “foreignness,” perceived hostility, just the fear of settling in a new place very often. . . .Timothy Springer was another one of those initial investors who placed cash directly into Moderna. As Forbes reports, “Springer was a founding investor of Moderna in 2010, when he put about $5 million into the company. Now, a decade later, that initial investment is worth nearly $870 million.” Langer as well, says Time magazine, was “one of the first” of Moderna’s direct funders. And even before their investments in Moderna, Timothy Springer and Bob Langer engaged in commercial ventures that improved health and human life.That journey is what innovators do, because any time you propose something that has no precedent, people basically criticize you. . . .

So I view immigration as kind of a philosophy of life, and that is to...leave one’s comfort zone, dare to try new things, to excel, and through that may cause progress to happen. And whether it’s physical immigrants or intellectual immigrants, it’s very much a big part of shaping my life.

Another lifesaving billionaire is Patrick Soon-Shiong, M.D. This story might seem, at first glance, to be one of taxpayer funding being the lifesaver. But soon Soon-Shiong arrives to provide the twist.

To be used along with docetaxel or nab-paclitaxel, there is yet another drug that has been of assistance to patients undergoing chemotherapy, this one being the first employment of recombinant genetic engineering for use against cancer. That is trastuzumab, going by the brand name Herceptin. From 1969 to 1980, scientists came upon a series of clues concerning the manner in which some inheritable genes are especially vulnerable to mutations that lead to cancer. These mutated genes are known as oncogenes. In 1982, a German-born scientist employed by Genentech Corporation, Axel Ullrich, identified a particular oncogene that would later be named Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 —“HER-2.”

That Genentech’s executives were initially unsympathetic to the efforts of Axel Ullrich and Dennis Slamon is disappointing. It is also surprising as the company got its start through producing comparably revolutionary lifesaving treatments.

Since then, the exciting opportunities in biotechnology have expanded. The gene-splicing method of CRISPR takes advantage of a protein from bacteria called Cas9. Viruses such as bacteriophages prey upon bacteria, and bacteria have hence evolved their own immune systems to protect them. The chemical Cas9 is a weapon whereby the bacteria slice viruses into separate pieces, neutralizing the threat they pose.

Many vaccines other than the one for COVID have also been a blessing. Perhaps the vaccine creator to make the most news over the past several years has been Paul Offit of CHOP — the Children’s Hospital Of Philadelphia. Anti-vaccination activists castigate Dr. Offit as “Dr. Profit.”. And, sadly, Offit does not disagree completely about there being something shameful in that moniker.

Besides the ones for COVID-19 and the rotavirus, there are other profitable lifesaving vaccines. Among them is the one for the bacterium Haemophilus influenzaea Type B — “HiB,” for short. HiB has frequently caused childhood meningitis, which, in turn, often led to paralysis, deafness, blindness, developmental disabilities, and death.

Medical treatments such as vaccines, cancer drugs, and genetically engineered insulin are not the only lifesavers. Medical devices matter as well. Cardiac patients have benefited greatly from the feats of C. Walton Lillehei, Earl Bakken, Manuel “Manny” Villafaña, Wilson Greatbatch, and Kurt Amplatz.

The problem for a small inventor today is the FDA. So many laws have been written that a small operator can’t do something like a pacemaker. The regulations are so complex and the required testing is so expensive that a small company can’t do it. . . . If I did today what I did twenty years ago, I would go to jail. Imagine making pacemakers in a barn and taking them to a hospital and putting them into patients! But we did it, and it worked. It was done very ethically, and a lot of people are alive today because of that work.When it came to finding a firm to manufacture units of this invention, Greatbatch first approached Medtronic. Given the very machine that launched the company, this seemed a natural fit. Ironically, Medtronic ultimately rejected Greatbatch’s model. He then pitched his creation to one of Manny Villafaña’s corporations — Cardiac Pacemaker, Inc. (CPI).

Another medical technology not to be overlooked is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI scan can detect cancers, brain injuries, multiple sclerosis, and even dementia. It can even detect some diseases that CT scans cannot, such as prostate cancer and uterine cancer. According to the American Chemical Society, the number of lives saved by MRI scans is in the “millions.”

Raymond V. Damadian was a great contributor to the creation of this technology. Sadly, his patents have not always been respected as well as they should have. In 1997, he won a patent infringement suit against General Electric for $128.7 million.

On account of his troubles, Damadian has become a public advocate for the rights of inventors. Coauthoring an op-ed in 2011 where he favorably cites Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, he expresses concern about changes in patent law that undermine the protections of independent inventors.

Damadian’s machine was excellent, but there was always room for improvement. One major difficulty has been that the MRI machine was so large that it would fill the space of an entire room. Yet many patients most in need of an MRI scan are severely disabled and cannot even be wheeled to that special room. For that reason, Jonathan Rothberg — the same man who contributed to gene-mapping technologies and co-invented home COVID test kits — decided to do something in this field, too. He had his company Hyperfine come out with Swoop, a portable MRI device that can be wheeled to the patients. Many hospitals in developing countries cannot afford to install a conventional MRI scanner, but they can afford a Swoop. It is $50,000, which is twenty times cheaper than is a conventional MRI.

As Fast Company magazine puts it, “This portable, affordable new MRI machine is already saving lives around the world.”

Bravo for Baekeland | Leo Baekeland and Plastics in Hospitals | ^

Something else which saves lives, but which is given much less credit for doing so today, is plastic. For the past several years, we have heard much about its products polluting the ocean and remaining a threat to animals for the very reason it has been a boon to humankind — that it is so durable. Sometimes it seems as though people have come to think of plastic as being an inherently bad material.

The reality is that the substance itself should not be blamed. There are technological remedies. Scientists have discovered microorganisms and arthropods that eat plastic. Theoretically, these organisms can be let loose upon plastics in landfills before the materials reach the ocean. More pertinent is that the properties of plastics — that they manage to be both lightweight and durable — has made them ideal for various medical devices. They provide the material for bags in which donated blood is stored.

ScienceHeroes.Com credits blood transfusions with saving 1.1 billion lives. The plastics in which the blood was stored definitely facilitated a larger number of those procedures. There would have been far fewer of them had it not been for modern storage techniques.

A National Geographic piece that is fashionably unflattering toward plastics nonetheless quotes University of Massachusetts Lowell engineer Bridgette Budhlall: “Plastics for biomedical applications have many desirable properties, including low cost, ease of processing, and [ability] to be sterilized easily.” The National Geographic piece then continues that Dr. Budhlall also mentions that plastics can be changed with coatings that make them especially resistant to contagion by microscopic organisms. On account of how they have allowed for medical professionals to maintain hygiene, NatGeo admits that “plastic has revolutionized the medical industry over the past century...”

The first plastics were invented by Belgian-born chemical engineer Leo Henrik Baekeland. Having been paid $1 million by George Eastman for his special photographic paper, he could have been content with early retirement. Indeed, his contract with Eastman Kodak contained a non-compete clause. It stipulated that Baekeland could not commercialize any new photographic papers for the next ten years. Therefore, he took to satisfying his curiosity in other matters of chemical engineering. There were still millions of practical problems to be solved.

Plugging his newfound riches into his second major scientific enterprise, he invented Bakelite, an early plastic that would serve as a model for the others to be created throughout the twentieth century. This made Baekeland richer still. At age seventy-five, he sold his plastics company to Union Carbide for $16.5 million.

As with other entrepreneurs profiled in this essay, Baekeland was an eccentric. While having a conversation on a hot day, he would make a habit of walking straight into his swimming pool or the ocean fully clothed as he continued speaking. He did this nonchalantly as if there was nothing unusual about it.

Enemy of Arthritis | Percy Julian, Sr., and New Foam for Fire Extinguishers | ^

Some innovators invent both pharmaceuticals and safety devices. One of them was Percy Julian, Sr., born in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1899, the grandson of slaves. In spite of the heavy discrimination, Julian put himself through school and became a prominent chemical engineer. He became director of research at the Glidden Company where he extracted chemicals from soy and synthesized them into new compounds. First at Glidden and then at his own firm Julian Laboratories, which he started in 1953, he produced steroids to treat the sufferers of rheumatoid arthritis.

Julian and his chemists were able to make gains in efficiency to the point where on some products they quadrupled production. On account of these gains, between 1950 and 1956, Julian was able to lower the per-kilogram price of progesterone, an ingredient in arthritis medication, from $4,000 to $400.

But Julian’s work did not merely relieve pain; it also cut down the number of fatalities. In the early 1940s, he made improvements on the substances contained in fire extinguishers. As recounted on the website of the PBS series Nova, at Glidden he “extracted a soy protein used in fire-fighting foam, which saved thousands of lives during World War II.”

In 1961 he sold Julian Laboratories for $2.3 million — $20 million in 2022 U.S. dollars. Much of the proceeds he would donate to the civil rights movement.

Duane and the Detector | Duane Pearsall and the Smoke Detecdtor | ^

Percy Julian’s activism is an inspiration, but the shiny light reflectors on the road are seldom cited as an inspiration for anything. Yet these reflectors make a big difference in their own right. They keep motorists’ eyes on the road and prevent fatality. They were invented and marketed by yet another Percy — Percy Shaw of the United Kingdom. When he died in 1976, he left behind an estate of £193,500. In 2022 money, that is 2 million U.S. dollars. With his fortune, he purchased a mansion in which, like Leo Baekeland, he showed off his quirks. He bought for television sets and placed them all in the same room. He had all TVs playing at once, each on a different channel, with the volume muted.

He said that this was because when guests came over, they all wanted to watch TV but couldn’t agree on the station.

Percy Shaw’s four TVs did not make a lot of noise, but that was the very purpose of the devices of our next inventor. For decades, inventors and engineers had been trying to figure out how to create an alarm that would warn a home’s residences of a fire before it grew too large for them to escape. These inventors and engineers concentrated on trying to make a machine that would detect heat. By the early 1960s, these heat detectors were already being installed in residences. They would continue to be selling well into the late 1970s.

Yet their weakness was in their unreliability. The detection of a high temperature was not always the same as identifying the outbreak of flames.

In 1963, even as heat detectors were on the market, home conflagrations continued to kill thousands of Americans. That same year, engineer Duane Pearsall had set his sights on something else. The presence of static electricity disrupted operations in factories and photographic laboratories.

To address that interference, he started the company Statitrol — short for “Static control” — and, with assistants, constructed a device to measure ions in the air. He dubbed it his “static neutralizer.” One day as he was tinkering with it, a colleague lit a cigarette. The rising smoke triggered in the neutralizer and it blared uncontrollably. Many other people would have dismissed this reaction as just another complication or inconvenience, and forgotten about it. And Pearsall might have been one of them, had he not mentioned the incident to an engineer friend from Honeywell Corporation. This colleague inferred that this could be ideal for warning homeowners of the presence of a fire.

It turned out that heat detectors were not the best in warning about any emerging blaze. A stronger indicator was smoke. This inspiration led Pearsall to take the knowledge he had already gained from his progress with the static neutralizer and to apply it to this new inquiry.

The models put out by Statitrol were impressive. Yet Pearsall still had to work out the kinks, and he still had to demonstrate that his smoke detectors provided an advantage that the already-established heat detectors did not. Independent investigators, though, noticed the difference. Writing in 1974 in an academic paper for the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), National Bureau of Standards research engineer Richard G. Wright assessed, “...smoke detector technology has advanced to the point where the judicious installation of one or two smoke detectors could be more effective than a house full of heat detectors in alerting dwelling occupants to a fire” (page 71).

History has borne out Wright’s evaluation. Yet there was already evidence for it by 1962. In that year, J. H. McGuire and B. E. Ruscoe found that the lifesaving potential of the presence of heat detectors in a home was 8 percent, whereas it was 41 percent for smoke detectors (“The Value of a Fire Detector in the Home,” Fire Study no. 9 [November 1962].”

In 1972, the rate of mortality from house fires in the United States was 57 in a million people. As smoke detectors and other safety measures became more commonplace in the home, that rate reduced. By the year 2009, it was fewer than 12 in a million.

And in contrast to the heat detector installations being between $700 and $1,200,

Pearsall’s smoke detector debuted in the Sears Roebuck catalog two years earlier priced at $37.88.

Yet Pearsall could have lost his chance at saving lives had a reputed champion of safety and lifesaving succeeded in thwarting him. That was corporation-bashing crusader Ralph Nader. In 1976, the Health Research Group division of his group Public Citizen sent a letter to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The message was dire in tone. Sidney Wolfe, the medical doctor and activist leading the Health Research Group, noted that smoke detectors emit radioactivity. For that reason, Nader and Dr. Wolfe demanded that the NRC place a moratorium on its sale and use. Public Citizen denounced these gizmos as “mindless and dangerous,” followed by a demand that four million of these units be recalled.

Prior to Nader and Dr. Wolfe ever making a fuss, Pearsall already implemented precautions concerning the radiation. When Pearsall started out, his SmokeGard transmitted half a microcurie of Radium 226. Pearsall had already shrunken that to a single microcurie of Americium 241.

Fortunately for Americans who since have been warned of fires by their smoke detectors — and otherwise would have died — the wish of Public Citizen went unfulfilled. To its credit, the NRC rejected the demands of Nader and Wolfe. The NRC replied that the dosage level is what determines whether exposure to radiation and most chemicals is safe or dangerous, and that the dose of radiation from smoke detectors was too small to harm a household. The regulatory agency then noted that a person would already be exposed to over a hundred times more background radiation during a flight across the United States.

To that, Sidney Wolfe replied, rather unscientifically, “The issue is not how much radiation is released but why this extra amount of radiation exposure is necessary at all.” He was referring to how smoke detectors released slightly more radiation than did the heat detectors. He then insinuated that the heat detectors were already adequate in alerting people about fires. The figures on the reduction in deaths from house fires in the following years suggest something quite disparate from what Sidney Wolfe and Ralph Nader assumed.

Statitrol grew so much that, at one point under Pearsall’s leadership, the company boasted over one thousand employees. Yet Pearsall never forgot his hardships when he directed a team of just a few members. Following his success, he remained an advocate for small business. In 2004, the Worcester Polytechnic Institute gave him an award for “saving upwards of 50,000 lives from deadly residential fires over the past 30 years.”

Excellent Electricity | Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, the Air Brake, and Electric Heating | ^

Even when the technology is not made for an explicit lifesaving purpose, but is instead intended for uses that are more general, it could save lives. That happens with electricity generation. Suffering from the cold at night has threatened human lives since the Stone Age. Deaths from cold annually outnumber those from heat.

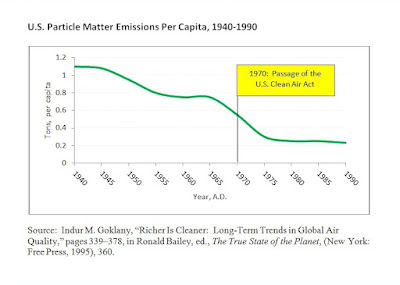

Prior to the advent of indoor electric heating, people had to heat their homes by burning firewood. In developing countries, where there are still millions of people cannot access to electricity, such people still have to do it, sometimes with dung. Although there is romance to the image of relaxing before a warm fireplace, this practice carries its own hazards. The fumes can build up in the lungs and ultimately cause growths in them. This is “indoor air pollution,” and there are figures that illustrate the extent of the damage it does.

Worldwide, but mostly in the developing countries, this indoor air pollution proves lethal for large numbers of human beings. Among the higher estimates is 3.5 million per year. That is 200,000 more than the number of people annually killed by the outdoor air pollution that is more familiar to us. This also exceeds the annual death rates of both malaria and AIDS combined. Even the lowest estimates are around 1.6 million per year.

The total number of casualties from indoor air pollution is 260 million, which is almost twice as many as those from all of the twentieth century’s wars put together.

The scourge of indoor air pollution is evident even in rich countries where people have access to electricity but, for aesthetic reasons, opt for fireplaces anyway. Eight percent of Britons do this, and half of them are categorized as “affluent.” Such a small portion of the U.K. population still heating with fireplaces is enough to excrete three times more air pollution than do all the country’s automobile emissions. Wood-burning stoves in the U.K.’s urban areas account for almost 50 percent of Britons’ exposure to carcinogens in particles of air pollution.

Considering all of the perils of the heating methods that people must rely upon when they do not have electricity, this absence is identified properly as “energy poverty.” The flip side is that these dangers and deaths are eliminated when people do have proper access to electricity — especially, in this context, electric heating.

Eighty-seven percent of the global human population currently has access to electricity. And, according to Our World in Data, 4.1 percent of the global population dies from indoor air pollution. That means that out of the Earth’s 7.9 billion people, that is 6.873 billion with electric power. Were it the case that this 6.873 billion did not have electricity and therefore had to rely on fireplaces for heating, and 4.1 percent of them died from indoor air pollution, that would be 281.793 million killed.

This suggests that simply in having electric heating in their homes, at least 281 million people have been saved.

By creating the electricity generation industry, rivals Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse contributed to this lifesaving. And, prior to this, Westinghouse had already made his first fortune with a different lifesaving device.

As it was for his future adversary, invention had been a lifelong vocation for Westinghouse. A prodigy, at age fifteen he had already designed his own rotary engine. A few years later, he would come up with the idea for which he was most famous. Traveling via locomotive then was especially perilous. For a train to stop, a brakeman would have to ride on the roof of a car. This brakeman would have to apply the brake on each car separately and then move on to the next car until the brakes were applied on all of them. On account of this arduous sequence of tasks, the train would normally travel for an entire two miles between the application of the first brake and the time that the train finally ground to a halt. In one year, as many as 5,000 American brakemen were killed during this sequence.

As a young man, Westinghouse came to the rescue with his air brake system. The train’s wheels would be connected to a tube. When the brake was applied, it sent compressed air through the tube that acted on the wheels of all the cars simultaneously. The distance the train would continue to travel upon application of the brakes was now in hundreds of yards instead of thousands.

At age twenty-one, Westinghouse searched for investors. He went to railroad magnate “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt, Sr., who had made his own financially risky innovations throughout his life and who, by this time, had become the richest man in the country, if not the world. Upon hearing Westinghouse’s idea, Vanderbilt cackled, “Do you mean to tell me that you can stop a railroad train by wind?”

Westinghouse replied, “Well, yes. Inasmuch as air is wind, I suppose you are right.”

Vanderbilt had heard enough. He concluded, “I have no time to waste on fools.”

The young Westinghouse remained undaunted. He introduced his air brake to the market in 1872. Twenty-one years later, Congress passed the Railroad Safety Act (RSA), mandating that railroads have their trains make use of both Westinghouse’s air brake and another lifesaving innovation, the Jenny coupler. However, there was a grace period; the statute would not go into full effect until 1900. Many media, such as the TV program Modern Marvels, credit this legislation with railroads adopting these safety devices.

Yet long before the law went into effect, forward-thinking executives already knew that the hazards associated with locomotives made prospective passengers reluctant to ride and prospective employees skittish to apply to work for their railroads. By 1876 — over sixteen years prior to the Railroad Safety Act’s passage and over two decades prior to it going into effect fully — over 37 percent of railroad passenger cars in the United States already had Westinghouse’s air brake installed.

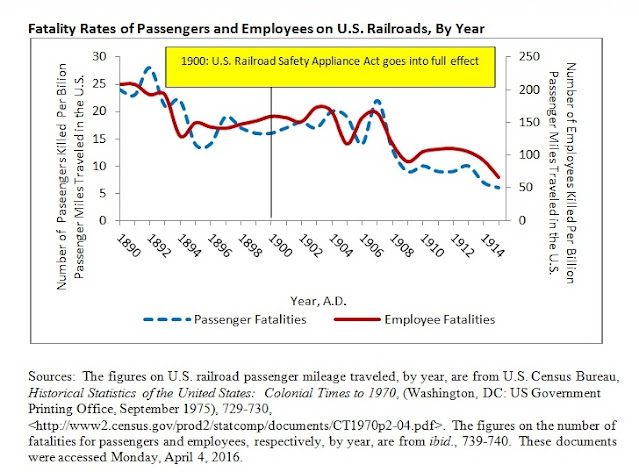

According to engineer Gary McCormick, this invention saved “hundreds of lives each year.” Sure enough, between the years 1890 and 1915, the fatality rate fell by more than 63 percent for railroad passengers and by more than 61 percent for employees. And that was the trend prior to the RSA going into full effect. Between 1890 and 1899, the fatality rate dropped by more than a third for passengers and by one-fourth for employees.

Having established himself as a successful salesman his air brake, Westinghouse turned his attention elsewhere. He took the millions he earned and invested them in other endeavors, such as competing against Thomas Edison in the market for electricity.

Something else which saves lives, but which is given much less credit for doing so today, is plastic. For the past several years, we have heard much about its products polluting the ocean and remaining a threat to animals for the very reason it has been a boon to humankind — that it is so durable. Sometimes it seems as though people have come to think of plastic as being an inherently bad material.

Some innovators invent both pharmaceuticals and safety devices. One of them was Percy Julian, Sr., born in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1899, the grandson of slaves. In spite of the heavy discrimination, Julian put himself through school and became a prominent chemical engineer. He became director of research at the Glidden Company where he extracted chemicals from soy and synthesized them into new compounds. First at Glidden and then at his own firm Julian Laboratories, which he started in 1953, he produced steroids to treat the sufferers of rheumatoid arthritis.

Percy Julian’s activism is an inspiration, but the shiny light reflectors on the road are seldom cited as an inspiration for anything. Yet these reflectors make a big difference in their own right. They keep motorists’ eyes on the road and prevent fatality. They were invented and marketed by yet another Percy — Percy Shaw of the United Kingdom. When he died in 1976, he left behind an estate of £193,500. In 2022 money, that is 2 million U.S. dollars. With his fortune, he purchased a mansion in which, like Leo Baekeland, he showed off his quirks. He bought for television sets and placed them all in the same room. He had all TVs playing at once, each on a different channel, with the volume muted.

Even when the technology is not made for an explicit lifesaving purpose, but is instead intended for uses that are more general, it could save lives. That happens with electricity generation. Suffering from the cold at night has threatened human lives since the Stone Age. Deaths from cold annually outnumber those from heat.

Edison’s ambition did not end with inventing and selling his practical incandescent lightbulb. People could only use it if their houses had electricity, something that no one possessed. For there to be demand for Edison’s lightbulbs, he had to make available the means to light it. For that reason, he set to work on providing a system for distributing low-voltage, high-current electricity — direct current.

It is misleading to say that Edison’s system made use of direct current (DC) whereas Westinghouse’s was all about alternating current (AC). Rather, Edison’s system made use of DC only, whereas Westinghouse’s made use of both DC and AC.

The issue with Edison’s system was that DC would only send electricity over relatively short distances — the length of a street. If all of today’s homes were lit only through DC, there would have to be a power plant on every city block.

Conversely, when alternating current is employed, the electricity can be transmitted over many miles, across entire U.S. states. A single power plant could transmit high-voltage, low-current electricity over mostly undeveloped terrain until reaching an urban center. Once the electricity reached the urban center, it would be sent to a transformer that would convert the electricity to DC — low voltage, high current.

In 1938 — five years before his own death — Tesla described Westinghouse as

For such efforts, by the time of Westinghouse’s death, his estimated net worth was $50 million. In 2020 U.S. dollars, that is $1.29 billion.

Dying in 1931, Thomas Edison had a net worth of $12 million. In 2020 U.S. dollars, that is $204 million, putting Edison a fifth on his way to being a billionaire.

Considering that at least 281 million lives have been saved by the proliferation of electricity throughout homes, these fortunes were well-earned. These are the billionaires maligned in Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s diatribes.

And though Westinghouse and Edison were unusual in many respects, they were not unusual in being nineteenth-century entrepreneurs whose ventures had saved lives. The same applies to Gail Borden.

Glorious Gail | Gail Borden and Condensed Milk | ^

Pasteurization had yet to become widely adopted. In the 1850s, Americans could consume milk only as it was raw. A devoutly religious entrepreneur named Gail Borden saw the disastrous consequences of this failure in sanitation up close during his efforts to market a different product, a dried meat biscuit he promoted at the 1851 London World’s Fair. On the ship voyage home to New York, he could not help but notice the dairy cows aboard the vessel for the passengers. Drinking the raw milk made many of the children sick; some died.

Returning to his laboratory in New York, Borden experimented with boiling milk at 212 º F to disinfect it. This always resulted in his milk ending up burnt and tasting horrible. Undaunted, he finally gained new inspiration upon visiting a colony of members of the Shaker religious order. He saw the Shakers boil their fruits in a special vacuum pan to dehydrate them. Everything else being equal, liquids boil at reduced temperatures when they are in an environment of lower pressure. Borden took to boiling milk in a similar vacuum pan, now able to do so at 136 º F without the burning the milk. Another effect was that it could be preserved over time, not being subject to spoilage.

The entrepreneur continued experimenting with different designs for vacuum pans. Upon devising one that was especially functional, he patented it in 1856. According to Vintage News, Borden’s technique at preservation “saved thousands of children and men.”

From his business choices, Borden had amassed assets worth over $100,000 — $2.7 million today.

Thomas Midgley, Now Depicted As Evil, “Has Saved Millions of Lives” | Thomas Midgley and Safer Refrigerators and Air Conditioners | ^

Just as George Westinghouse availed to people a safer way to protect themselves from the cold, Thomas Midgley availed to them a safer way to protect themselves from the heat. He did this through his improvements to air conditioning and refrigeration.

Attempts to control the temperature and air quality had been attempted before. In Florida in 1851, a medical doctor named John Gorrie had been treating fever in malaria patients. He invented an ice machine for cooling the room. It brought in air and compressed it. The air then ran through pipes, cooling as it expanded before reaching the patients. For this, newspapers denounced him and his invention as unholy. They considered it “natural” and God’s plan for people to bear the heat of the day. For Dr. Gorrie to help people avoid that was an unnatural tampering with nature and God’s will. Such thinking had long predated similar fears of genetic engineering.

When air conditioning was refined and made more sophisticated decades later, it was to address the problems connected to a particular type of heat — humidity. And this was not for general consuming public but for industrial applications. The concerned businesses were not as interested in doing anything about dry heat.

Although more strongly associated with a contraption that Willis Haviland Carrier assembled in 1902, the term “air conditioning” was coined four years later by Stuart W. Cramer, Sr. He had been designing and running cotton mills throughout North Carolina. Inspecting them, Cramer observed that in greater humidity, his mills’ wheels spun faster. He was resolute in hitting upon some configuration by which he could control the humidity to ensure that the wheels would rotate at the most consistent and convenient rate.

Air conditioning involves liquefied or gasified chemicals flowing through a box and warming or cooling the air inside it. A fan blows the treated air out of the box and to where the cooled or warmed air is desired. Use of gasified or liquefied chemicals flowing through tubes to control the temperature is also the principle behind refrigeration. In Cramer’s case, moisture was added and the vents blew moistened air throughout the mills.

Four years earlier in New York state, twenty-five-year-old Willis Carrier had been mulling over the opposite objective — how to remove moisture from the air. The Sackett and Wilhelms Lithography and Printing Company attempted to print newspapers in a multi-color format. It did so by a laborious process of one color at a time, whereby ink of that color was added in a single layer. In order for the page to be colored as planned, every application of a layer of ink had to align precisely with the others. Yet the humidity had unpredictable effects on the paper, which shrank or expanded in odd fashions. As several layers of different-color ink were added, the final result was a distorted image. To do something about the humidity, Sackett and Wilhelms went to Carrier’s employer at the time, the Buffalo Forge Company.

As Carrier’s invention blew temperature-controlled air through its vents, causing the air to circulate, metal plates inside of the machine collected and trapped the water droplets that had been circulating.

In 1915, Carrier left Buffalo Forge to start his own company, taking several other Buffalo Forge engineers with him. He had heard of Stuart Cramer’s speech from nine years earlier and adopted the term “air conditioning” for the name of his own company. He had credited Cramer as an inspiration for several ideas he was putting into practice. Carrier’s air conditioning gained greater recognition and appreciation when installing it in movie theaters during the summers of the Great Depression. Gradually, over time, the general public came to accept air conditioning, forgetting the crowing from decades past about how this technology was unnatural and sacrilegious.

Both Carrier and Cramer enjoyed commercial success. Once Edison and Westinghouse had established the technology, Cramer would go on to build several power plants that provided Texans with electric heating and thereby liberated them from the indoor air pollution that came from fireplaces. In this manner, Cramer protected customers from both the heat and the cold.

From these enterprises, Cramer had amassed enough cash that his descendants would be prominent figures of high society. His grandson, Stuart W. Cramer III, invested the inheritance into oil and competed with Howard Hughes for the romantic affection of not one but two Hollywood actresses — Jean Peters and Mighty Joe Young star Terry Moore.

Even as Carrier enjoyed success, there remained a tremendous disadvantage with air conditioners and refrigerators — the gases and liquids inside of them released fumes that were toxic to those who handled them. These gases and liquids were even flammable. They had caused fires that proved to be fatal. This problem was finally rectified in 1950 by a General Motors engineer in Ohio named Thomas Midgley.

If you run a quick Google search this instant on Thomas Midgley, in the results you will find that the man is routinely denounced as misguided at best and evil at worst. He invented leaded gasoline, which proved to be a major toxin. It usually goes unmentioned that Midgley’s work on air conditioning and refrigerants, which is demonized even more ferociously, has actually saved many lives.

At General Motors, Midgley reported directly to multimillionaire Charles F. Kettering, the engineer who invented the modern automobile’s self-starter. Kettering is the reason why car engines today turn on with a turn of the key. GM spun off a subsidiary company, Frigidaire, to refine air conditioners and refrigerators. Such technologies were connected due to GM’s interest in providing air conditioning in its vehicles.

Although leaded gasoline ended up being poisonous, in 1928 Midgley was genuinely interested in finding a technique to produce air conditioners and refrigerators that would not harm their users.

With two assistants, Midgley examined a pocket-sized periodic table. He knew the properties that were needed. Besides being nontoxic and nonflammable, it had to be stable with a boiling point within 0 to -40 º C. The element fluorine would work well except that it was toxic. He thus considered whether the fluorine could be rendered safe if it was bonded to some other elements to form a new compound. After all, hydrogen is dangerous all by itself as an element, but a reaction between two hydrogen atoms and a single oxygen atom results in relatively safe H2O. Likewise, fluorine would be rendered safe if bonded with chlorine and carbon. The seeming answer to the problem was CFCs — chlorofluorocarbons, with which GM tagged the brand name “Freon.”

Still, there was an issue of whether it might turn out later that CFCs did not function as well as they seemed. Hence, General Motors had a backup. Midgley and his team also considered another class of compounds — hydrofluorocarbons, or “HFCs” — that potentially bore the same beneficial qualities as CFCs without the same drawbacks. If ever there was an unforeseen problem with CFCs, then HFCs might serve as a replacement.

Because the gases in air conditioners and refrigerators had earned a reputation for being health hazards, in 1930 Midgley publicly demonstrated the relative safety of Freon. He lit a candle near the liquid. He boiled it in a bowl and inhaled the gases emerging from it. Then he blew the candle out. This presentation ended the public’s reluctance to purchase the new safe refrigerators and air conditioners.

Decades following Midgley’s death, other scientists discovered that sulfur dioxide emissions from the use of CFCs entered the Earth’s atmosphere and depleted the ozone layer. The federal government passed laws to phase out CFCs in the ensuing years. Yet, as science journalist Sharon Bertsch McGrayne notes, the HFCs that became the replacement in air conditioners and refrigerators in the 1990s were “all substitutes discovered by Midgley and his colleagues.”

In recent years, the HFCs have been blamed for posing yet another dilemma. Although they do not have the same effect on the ozone layer, they still contribute to greenhouse warming. Besides his invention of leaded gasoline, this is the other reason that Midgley has become widely denounced all over internet. For such reasons, it appears Pope Francis has revived the idea that this technology is sinful. He intones that the “growing ecological sensitivity” he desires in people still “has not succeeded in changing” the world’s most “harmful habits of consumption... A simple example is the increasing use and power of air-conditioning.” This is a vice that the pontiff deems “self-destructive.”

How capitalism itself can address the issue of greenhouse emissions from air conditioners and other machinery is a matter to which we shall revisit in Part Two.

With the public not yet conscious of ozone depletion or anthropogenic climate change, Midgley rendering air conditioners and refrigerators safe — at least in terms of coming into direct contact with them and handling them — was a boon to GM. This success had made Midgley a multimillionaire.

He was not able to enjoy his new wealth as much as he expected. Beginning in 1940, he was stricken with polio. He underwent intense physical therapy regularly in a swimming pool but he remained paralyzed from the waist down. Throughout his mansion, he set up a system of ropes and pulleys to help him go about independently. Yet one day his wife found him dead, strangled by these same hoists.

Many of the websites condemning Midgley frame this death as a fitting metaphor for the man’s life — Midgley was killed unexpectedly by one of his own inventions, just as he lacked the foresight on how his more-famous inventions would kill others.

Representative of this schadenfreude is YouTube presenter Matthew Santoro, who generally holds a reputation for being a nice guy. He cracks to his audience, “And I know a lot of you right now are like, ‘Aw, it should’ve been the lead poisoning that got him. That would’ve been poetic justice.’ And, to those of you, I say, ‘You’re kind of sick — and right.’” Yet chemistry professor and historian Carmen Giunta observes that Midgley’s own family and loved ones had concluded that Midgley had committed suicide with these ropes. The reason that they let the media report that this was an accident was that persons who killed themselves were stigmatized even more severely back then. By comparison, allowing the public to interpret Midgley’s death as an accident was to save face.

Furthermore, what is usually glossed over is that Midgley’s innovations in air conditioning and refrigeration saved lives very directly. This can be observed in the changes in heat-related mortality in Chicago over the course of a century. In 1901 in the windy city, there were 10,000 heat-related deaths. In 1955, that figure had dropped to 885. In the heat wave of July 1995, it was 300.

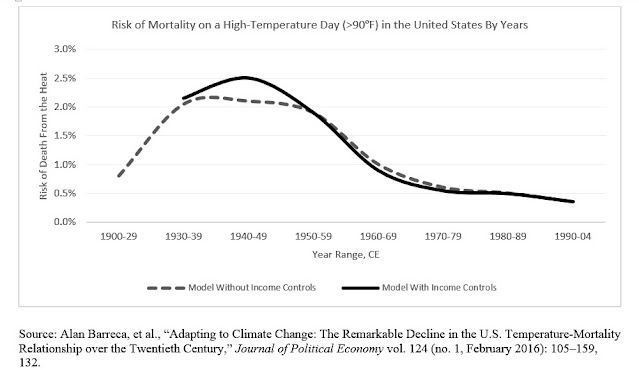

In 2016, a team of scholars including Carnegie Mellon economist Karen Clay published a scientific assessment of heat-related mortality in the United States throughout the twentieth century. The team found that between 1940 and 2004, the statistical risk of dying from heat in the USA on a day of over-90-º-F temperatures had fallen by over 60 percent. Between 1930 and 2004, the risk of dying from the heat on over-80-º days reduced by three quarters. And what was the major reason for this reduction? The team admits that the adoption of “residential air conditioning explains essentially the entire decline in hot day–related fatalities.”

It is fortunate, then, that this technology has become increasingly affordable to those of lower income. In 1950, less than 18 percent of all U.S. households could access this technology. By 1997, over 68 percent of U.S. households below the official federal poverty line now had air conditioning. By 2005, among those under the federal poverty line, it was over 77 percent.

Midgley has much to do with how, as was said by Aperion Care and as was published on the World Economic Forum’s website, 2 million lives have been spared of heatstroke from 1950 onward.

Sharon Bertsch McGrayne details how Midgley’s refrigerants saved lives through other avenues.

In his final public speech, “The Future of Industrial Research,” which he gave over the telephone, Midgley spoke these words that meet with disapproval

from almost every biographer who quotes them:

“Death Ray”? More Like “Life Ray” | Gordon Gould and the Laser | ^

Yet another invention that saves lives in a manner far from obvious is the laser. Had this invention remained under the control of the military, it probably would have not have been applied as anything other than a weapon. Thankfully, businesses have been able to adapt it for peaceful civilian purposes.

Lasers are essential to biometric scanners that take in biological data as their inputs. A laser scans an object and enters its reading into a computer that processes the data. This is what happens with bar codes at the grocery store checkout counter. It was by the same principle that Craig Venter relied upon such lasers when mapping the human genome — a development that, as we have learned, saves 5 million lives each year.

Lasers can also be employed in rescue efforts. When firefighters rush into a burning building, they do not know what obstacles inside will hinder them. Worse, the smoke obscures their vision. There would be some relief in having an updated-to-the-minute map of the structure’s interior prior to entry. Modern technology is making this possible.

Sonar (SOund Navigation And Ranging) works on the principle that the machine can measure the distance a sound wave travels before bouncing off an object. Through sonar, sound waves provide a three-dimensional map of an environment. Radar (RAdio Detection And Ranging) applies that same principle but uses radio waves instead of sound waves. Likewise, lidar (LIght Detecting And Ranging) does the same with laser light. As I type this, firms are working on arranging for lidar to provide 3D models of rooms for firefighters.

Lidar is also being utilized in self-driving cars. If this automation can reduce the rate of fatalities and injury on the road, still more lives will be preserved. Aperion Care anticipates that this application will eventually save 1.5 million lives annually.

Early patents on lasers came from the academicians Charles Townes and Arthur Schawlow. By 1957, engineer Gordon Gould developed his own plans that he would go on to patent. Then in 1960, Theodore Maiman built the first working model of a laser while employed at Hughes Research Laboratories, which did R-and-D for Howard Hughes’s defense contracting firms. Soon after this breakthrough, Maiman bristled at news media describing his creation as a “death ray.” The very following year, Hughes Aircraft already began studying the possible applications for lidar. Maiman would leave Hughes to found several other companies, such as Korad. At the time that Union Carbide purchased all of Maiman’s shares in Korad, the corporation had a personnel force exceeding a hundred people and annual sales greater than $5 million.

Gordon Gould won $46 million in his lawsuits over his patents, and made millions of dollars from other enterprises prior to that judgment being rendered.

That was how Gould, once a member of the Communist Party of the USA, became an arch-capitalist whose invention in subsequent decades would reduce the mortality rate.

In 1988, Gould provided his thoughts on his start as an independent inventor:

Gould’s $46 million is an appropriate reward for making possible the mechanism that would enable human genome mapping that would save five million lives per annum.

It is ironic, then, that this invention that is most commonly imagined and depicted in media as a lethal weapon has done much to extend human life.

Fritz and His Fertilizer | Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and Synthetic Nitrogen Fertilizer | ^

And there is something else that is ironic. Recall that a website frequently cited throughout this essay, ScienceHeroes.Com, was created by Billy Woodward to promote his book Scientists Greater Than Einstein. Although he describes himself as a “businessman” in the About the Author section, the book conveys its author’s unflattering impression of capitalism and for-profit enterprise.

Upon describing an action by Merck that he judges unethical, Woodward hisses that such an action is one “that those teachers who believe in Ayn Rand’s laissez-faire capitalism can teach in business schools and those who revere less the principle of selfishness can explore in ethics classes.” This disparagement is taken farther still on ScienceHeroes.Com.

The book’s final chapter argues that the private sector cannot and will not finance medical research adequately, and therefore there needs to be greater taxpayer funding of science. Woodward frames such “a choice for our future” as one of “Our Health” versus “Our Wealth.”

Yet in totaling the numbers of people saved by scientific projects, ScienceHeroes.Com provides information that is not completely consistent with Woodward’s generally unfavorable estimate of capitalist greed. The scientific endeavor that Woodward’s own website ranks as the one to have saved the most lives is . . . a for-profit venture.

This was the venture by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch in the industrial production of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer. It is well described on ScienceHeroes.Com in two articles penned not by Billy Woodward but by one of the writers assisting him, April Ingram.

Even for reasons other than his commercialism, Haber is not someone who would normally be described as a humanitarian. Prior to the ascension of the Nazis, Haber was a fervent German nationalist, especially in matters of military conflict. During World War One, Haber eagerly assisted the German government in weaponizing chlorine gas to be dispersed on French soldiers. Yet, even considering his role as one of the founders of chemical warfare, Haber instigated a project that holds the record in number of lives saved.

In 1899, the British scientist Sir William Crookes warned that the farms of the West were exhausting all the nutrients of their soil. Soon, they would not be able to grow any more, and the starvation would result. Haber took this to heart. A decade following Sir William’s dire prediction, Haber formulated methods to produce synthetic fertilizer, ammonium nitrate. As an executive of BASF, Carl Bosch refined those methods and applied them on an industrial scale. This became known as the Haber-Bosch process, and it made its namesakes very rich.

Still, the ascension of the Third Reich doomed both these men. Although Haber was a Christian, the Nazis held his Jewish ancestry against him and banished him from practicing any science. This was a crushing blow to someone previously so worshipful of the German state. Bosch went to Adolf Hitler directly to plead on Haber’s behalf. The industrialist informed the führer that purging Jewish scientists would set the country back on physics and chemistry for a hundred years. To that, Hitler simply replied, “Then we’ll just have to work 100 years without physics and chemistry!”

As the Third Reich held a tight grip on the national economy, it was easy for Nazi officials to inflict reprisals on Germans who did not express sufficient enthusiasm for their governance. As Bosch was highly critical of the Nazis, he was gradually stripped of his duties at BASF. Bosch sunk into depression and alcoholism.

Even decades after their death, the process of Haber and Bosch continued to change the world. After the famines imposed by Mao Tse-tung’s communism, China under Deng Xiaoping applied the process and ended the starvation.

ScienceHeroes.Com admits that the for-profit venture of Haber and Bosch has saved “over 2.3 billion lives.” In a Wired article from 2013, Bill Gates informed his readers, “Two out of every five people on Earth today owe their lives to the higher crop outputs” that the Haber-Bosch process “has made possible.”

All of the cases we have studied were about someone becoming obsessed with some problem or mystery and, in an attempt to solve it, exercised creativity in such a manner that resulted in saving people’s lives. This gives the lie to the claim by famous anti-capitalist Noam Chomsky, himself a multimillionaire who uses tax shelters, that it takes a “lack of curiosity and independence of mind...” for someone to reach “the high end” of “income distributions...”

A “lack of curiosity and independence of mind” sure does not describe Katalin Karikó, Jennifer Doudna, Percy Julian, Patrick Soon-Shiong, or any of the other innovators who struck it rich.

Value Added to the Natural Resources | ^

The author hopes that by now the reader is convinced that there are many instances throughout modern history of for-profit enterprises contributing to the extension of lives and the comforts within them. Yet those who look askance upon capitalism and billionaires are probably not satisfied. They can proclaim that these instances of lifesaving by billionaires such as Patrick Soon-Shiong and George Yancopoulos do not remove an inherently self-destructive attribute from commercial activity.

It is frequently stated that the global economy runs on nonrenewable natural resources. Such nonrenewable resources include petroleum, coal, tungsten, lithium, and silicon. The total quantity of such resources used as raw materials in goods and services only grows annually. Once these resources are used up, it is said, that will be the end of civilization. The persistence of this belief is a major reason why millions of people nodded in agreement as activist Greta Thunberg went before the United Nations to prevail upon various heads of State to abandon their “fairytales of eternal economic growth.”

The belief also feeds into Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s looking wistfully on the prevailing bias against capitalism that intellectuals had in the period between 1930 and 1979. She longs for a return to that “one point in time” where there was “almost a full consensus among our greatest thinkers in America that capitalism had an expiration date. This Late-Stage Hyper-Capitalism society of ‘just accrue’? This capitalism as an ideology of capital? And that ‘our number-one goal is to maximize profit at any and all human and environmental costs’? They knew that the idea was not sustainable.”

If the amount of wealth and prosperity is nothing more than a direct function of the quantity of nonrenewable natural resources, then the amount of wealth that can be enjoyed does come in a fixed quantity. It may be said that even if Patrick Soon-Shiong’s development of nab-paclitaxel saved the lives of cancer patients, the benefits came at the expense of everyone else in society. The resources that went into fighting metastatic breast cancer, and that went into the big fancy toys that Soon-Shiong and Jonathan Rothberg bought for themselves, are resources denied to everyone else. If Soon-Shiong and Rothberg own and have direct access over a total eight billion dollars’ worth of resources, that is eight billion dollars’ worth of resources less for the rest of Earth’s human population, especially its poorest.

Hence Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez pronounces, “No one ever makes a billion dollars. You take a billion dollars.” (emphases hers).

And she continues that “this system that we live in — life in capitalism — always ends in billionaires. This thing that we live in, starves people.”

To wit, the richer the billionaire is, the more it “starves people.”

That capitalism staves people is an odd claim to the employees of agribusinesses. It would have been news to Carl Bosch.

Yet Dan Riffle, the policy advisor and senior counsel to AOC who stated, “Every billionaire is a policy failure,” reinforces his employer’s zero-sum interpretation. After pretending to understand that more economic value can be created, Riffle makes it known that he will continue to deny, arbitrarily, the logical ramifications of such a fact. That is implicit in his proclamation that “it’s certainly the case that the bigger Jeff Bezos’s and Bill Gates’s slices of the pie are, the smaller everybody else’s slices of the pie are going to be.”

This is the same idea behind Bernie Sanders’s notorious proclamation, “You don’t necessarily need a choice of 23 underarm spray deodorants or of 18 different pairs of sneakers when children are hungry in this country.” Bernie’s presumption is that the resources that went into producing the twenty-three different types of deodorant and eighteen models of athletic shoes were resources that otherwise would have gone into feeding kids starving in the USA. The number of choices in hygiene canisters and fancy footwear is inversely proportional to the ability of America’s youngsters to have enough to eat.

The belief has been expressed by Percy Bysshe Shelley in words that would become cliché soon after they were published: “The rich have become richer, and the poor have become poorer...”

That slogan’s enduring popularity derives from a flagrant misunderstanding of the nature of wealth. The wealth that distinguishes a grand living standard from an inadequate one has less to do with monetary units than with the goods and services for which those monetary units are exchanged. More than that, that wealth is not an inherent function of the quantity of nonrenewable natural resources available. Instead, wealth is in the efficiency of the methods employed to derive life-enhancing value from such resources. It is therefore fitting that the term capitalism comes from “capital,” which has its origin in the Latin capita, meaning “head.” It is fitting because entrepreneurial innovators must use their noggins to conceive and implement such strategies to improve the efficiency by which the natural resources are used.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez blares, “Usually if you’re a billionaire, it means that you control a massive system. It means that you own oil supplies. . . . And to be ethical — if you’re a billionaire today — the thing you need to do is give up control and power” over those resources.

She talks as if petroleum was always inherently worth being in everyone’s control collectively, and then a small cabal of billionaires came and usurped that control all for itself. In reality, the default was a gallon’s worth of crude oil in the Stone Age and even the 1700s was of relatively little advantage to anyone. From the Middle Ages to the eighteenth century, farmers hated it when they found the black sludge. The foul-smelling goop seeped and damaged their crops. The presence of oil on their land only reduced marketplace demand for the property. Striking oil only became a plus and not a minus when Canadian geologist, chemist, and entrepreneur Abraham Gesner discovered and publicized the properties of petroleum that made it an ideal as a source of fuel, one rivaling the utility of whale oil.

That is, a gallon’s worth of crude did not have an inherent value. It gained value subsequent to the fulfillment of two conditions. The first condition was for a scientist such as Gesner to apprehend how that crude oil can be made useful for human beings. And even the fulfillment of that first condition, by itself, was not enough. Once Gesner established that kerosene could be isolated from crude, and that kerosene could light a lamp, that still would not ultimately help anyone who wanted to light a lamp if not for someone bothering to separate the kerosene from the rest of the gunk.

There was nothing obvious about it. That brings us to the second condition that had to be fulfilled for the petroleum to become valuable — someone had to bother undertaking the task of separating the kerosene from the crude and bringing it to market. As anyone with unfulfilled dreams can attest, dreaming up a great plan is a cinch in comparison to following through on it and keeping the commitment. In this instance, someone had to bother setting in motion the separation.

The follow-through on an endeavor so complex often takes the effort of a team of specialists that must be directed by a leader who, while not knowing everything a specialist does, retains a contextually adequate understanding of those differing areas of specialty. The follow-through needs a leader who can take into account that adequate understanding of those different specialized areas and integrate all the comprehension into a plan that the leader must commit to executing. And it is the leader who assembled that team in the first place. The leader must wrangle the engineers who design the equipment that the laborers will operate manually. The leader must instruct both sets of employees so that each set complements the work of the other. That is the entrepreneurship introduced by pioneers in the industry such as Abraham Gesner and George Bissell, and which was taken to a more sophisticated level by John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

Even as kerosene was isolated from the crude, Rockefeller noticed that the rest of this black glop was going to waste. He sought out and cooperated with experts who could discover uses for the rest of the substance. Then he sought out and cooperated with experts who devised the practical methods for making this waste into problem-solving products in their own right. Then he sought out and cooperated with parties who would conscientiously implement those methods. Rockefeller had to keep his eye on the big picture in the whole operation even as he had to ensure that every specific separate task in the operation went smoothly. He did this more competently than anyone before him did — cutting down the waste of every input of natural resource — and that is how he became the first billionaire in American history.

An example of the waste reduction has to do with sulfur. Much of the crude was found in sulfur deposits. Refiners such as Rockefeller were desperate to separate the kerosene they needed from this sulfur. But Rockefeller suspected that this sulfur could serve a valuable function as well, even if that function was not yet known. Ancient Romans collected it to heat baths, but no one had yet an ability to collect giant quantities of sulfur and apply it to an industrial purpose. That was until Rockefeller sought the assistance of German immigrant Herman Frasch.

Not only did Frasch remove the kerosene from the sulfur; he figured out new industrial sequences for extracting giant quantities of sulfur from natural deposits. Upon recognizing an underground sulfur deposit, he pumped giant quantities of heated water into it. The heated water liquefied the buried sulfur. Then Frasch blew compressed air into the deposit to push the sulfur up the well.

This newly accessible sulfur turned out to be an important ingredient in the first widely used antibiotic, sulfa, which went by the brand name of Prontosil. This medication saved thousands of soldiers’ lives during World War One.

As a consequence of his achievements, Rockefeller purchased Frasch’s patents and made him Standard Oil’s director of research. The German’s net worth at the time of his death in 1914 was $5 million, $128 million in 2018 U.S. dollars.

It was not obvious to Stone Age people that sulfur could be of use to them. It was a nasty, foul-smelling chemical. It took forward-thinking entrepreneurs to transform such a con into a pro. And this principle applies to so much more than petroleum and sulfur. The economic usefulness of various natural resources generally is far from obvious when those natural resources are first encountered.

It was not obvious to the ancient humans who first encountered petrified tree sap that one day it could be placed in telegraphs to have them transmit electrical signals. Nor was it obvious to the first caravans that the sand over which they traveled could be converted into cables that one day would enable one person to communicate instantly to someone else on the other side of the planet. And it was not obvious to the humans who first observed lithium that such a metal would be an excellent conductor in tiny rechargeable batteries powering telephones and computers fitting in their pockets. Nor was it obvious that such a metal one day would be invaluable to keeping hearts pumping, as do the lithium-iodide batteries in Wilson Greatbatch’s implantable pacemakers.

The extension or improvement of life that someone gets out of a good or service is what can be called “economic value.” That is wealth in its most direct form. And this economic value is not fixed and intrinsic to units of natural resources. It is instead to be found in human methods for making use of those resources. This realization was made at least as far back in time as the works of pioneering Enlightenment philosopher and medical scientist John Locke.

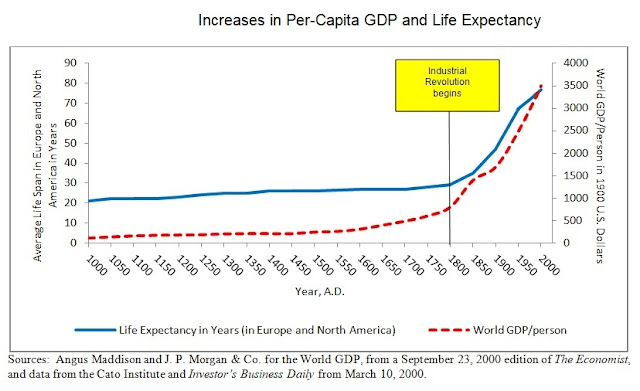

In Chapter 5 of his Second Treatise of Government, Locke points out that insofar as people want to a relatively decent life, scrounging in an untamed wilderness will not be adequate. Among hunter-gatherers who, for over 95 percent of our species’ history, tried to live off the land, there has been an infant mortality rate of 25 percent.

It is often claimed that observations of such hunter-gatherers having an average lifespan of 30 years is misleading. It is the high infant mortality rate that drags down the average, it is said, which would be much higher if not for that infant mortality rate.

To such a statement, it must be replied that the high infant mortality rate is not unimportant, especially to those of us who have children. Secondly, even among hunter-gatherers who survived infancy, the mode age of death was lower than that of modern industrial people. We will revisit this topic near the essay’s conclusion.

In accordance with Locke’s train of thought, it is the case that, to the extent that settlers in the wilderness want their homesteads to have an infant mortality rate far lower than 25 percent, they must make changes to this land. A farmer must dig crops and irrigate the terrain. Locke referred to such changes as “labor,” which Karl Marx and his followers tried to misconstrue as mere physical labor with one’s muscles, the sort of labor performed by a factory’s rank-and-file. Locke did not deny the importance of a homesteader making physical use of her muscles, but implicit in Locke’s argument is an even more important and value-adding form of labor. That would be intellectual labor. That is the intellectual effort of selecting which crops to plant during which seasons and of planning the routes of irrigation.

The “extent of ground is of...little value,” Locke wrote, in the absence of this creative entrepreneurial planning. In his mind,

The economic value that a business produces for its customers is called “output.” “Inputs” refer to the resources that must be used up in the process of generating the output. Inputs include both human labor and the natural resources that the operation entails.

As a firm must trade its own assets to acquire any input, every input adds to the firm’s expenses unless the firm is able to shift such expenses forcibly onto other parties. One example would be for the firm to steal its resources from someone else. That is consistent with the caricature of corporations being evil, but it actually clashes against the very principle of capitalism. Capitalism is contingent upon the enforcement of private property rights. To the extent that a firm coercively plunders someone else, the firm behaves in opposition to capitalism itself. Plunder is stopped to the extent that private property rights — and, with them, capitalism — are enforced consistently. We shall revisit that principle by the essay’s end with respect to pollution and industrial contributions to climate change.

Another method whereby a firm can elude paying the costs of its inputs is for the firm to receive direct taxpayer funding. Insofar as the firm successfully lobbies for this to happen, the firm is redirecting its own expenses onto the taxpaying public. This coercive redistribution is not pro-capitalism nor is this even, as it is often pegged, “pro-business,” “pro-corporation,” “corporationism,” or “corporatocracy.” The costs of a particular business or corporation may be reduced, but this is the result of resources being snatched from the owners of still other businesses and corporations. It is illogical to label this as if it were free capitalist enterprise, as that coercive intrusion leaves those other parties unfree to capitalize on their own enterprise. That is not pro-business any more than the State privileging one human at the forcible expense of another is “pro-human.” In effect, inasmuch as we want businesses to pay their own way, we must oppose direct taxpayer subsidies to them, even ones that perform work as salutary as Moderna’s.