The Shortest Version

INTRODUCTION

PART ONE: PROFILES OF LIFESAVING FOR-PROFIT ENTERPRISES

* Creativity in the Age of COVID – Makers of the COVID Vaccine

* Patrick and Paclitaxel – Patrick Soon-Shiong and His Cancer Drug

* Index to Additional Case Studies of Lifesaving For-Profit Initiatives

*Fritz and His Fertilizer – Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and Synthetic Nitrogen Fertilizer

PART TWO: HOW, CUMULATIVELY, BILLIONAIRES SAVE BILLIONS OF LIVES

* Value Added to Natural Resources

* Natural Fact One (of Two): Resource Substitution

* Natural Fact Two (of Two): Greater Utility From Fewer and Smaller Inputs

* The Carrying Capacity of Land

* Improved Productivity Helps People on the Lower Income Distribution

* Goods That Have Not Decreased in Real Price

* The Poor Get Richer

* What Capitalism Can Do for the Climate

* Capitalism Vs. Hunter-Gatherer Life Vs. Socialism

* Capitalism Vs. Taxpayer Funding for Basic Research and R-and-D

CONCLUSION

INTRODUCTION | ^

America’s billionaires are rich in their finances and poor in reputation. They have not been getting good press lately.

For much of the past few decades, the common attitude in America was that it is morally permissible to become a billionaire as long as one “gives back” in the form of philanthropy. That was the attitude formalized in The Gospel of Wealth penned by the richest man of its day, Andrew Carnegie. But over the past several years, the debate has shifted to whether it should be legal for any entrepreneur to become a billionaire at all.

Heralding this change was a January 2019 interview that left-wing writer Ta-Nehisi Coates conducted with then-freshman U.S. Sen. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. “Do we live in a moral world [if it is one] that allows for billionaires?” Coates asked her. “Is that a moral outcome?”

“No, it is not,” she replied. For this, she received uproarious cheers and applause.

She went on, “I do think a system that allows billionaires to exist — when there are parts of Alabama where people are still getting ringworm because they don’t have access to public health — is wrong.” Here she insinuates that an entrepreneur possessing billions of dollars’ worth of wealth somehow contributes to those Alabamans being too poor to receive adequate protection from, and treatment for, ringworm.

Sen. Ocasio-Cortez’s answer made headlines. It became apparent that many people in the United States and other countries agreed wholeheartedly with it. Almost as famously as his boss, AOC’s policy advisor and senior counsel Dan Riffle was quoted throughout the media proclaiming, “Every billionaire is a policy failure.”

Still more notorious than AOC is a man with seniority over her in the U.S. Senate, Bernie Sanders of Vermont. “There is something profoundly wrong,” he shouted in his announcement for his 2016 presidential run, “when in recent years, we have seen a proliferation of millionaires and billionaires [actually, ‘MILLIONAYAZ AND BILLIONAYAZ’] at the same time as millions of Americans are working longer hours for lower wages and we have shamefully the highest rate of childhood poverty of any major country.”

Note the implication here — as with Sen. Ocasio-Cortez — that the “lower wages” and “child poverty” are at least partially caused by this “proliferation of millionayaz and billionayaz.”

That billionaire entrepreneurs have such an unflattering image can be seen even in attempts to compliment them. Such can be gleaned a video essay by pop-culture commentator Lindsay Ellis. Despite her overall sympathies for the anti-capitalist message of the computer-animated movie adaptation of Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax, she found herself vicariously embarrassed that it was presented in such a ham-fisted manner. In a gesture of perfunctory evenhandedness, Ellis states what she apparently considers to be the strongest argument in favor of for-profit commerce: “...corporations employ people and make us stuff — not useful stuff, but stuff.”

The triteness of her evaluation would not be so concerning, except that it seems even many of the most prominent “defenders” of free enterprise tacitly agree with this characterization. The best that can be said of market economics, it is believed, is that businesses “make us stuff,’ stuff that is “not useful.” The run-of-the-mill defense of capitalism is that it incentivizes the production of “stuff” much more effectively than do the State-owned enterprises of socialism. Socialism might manufacture not-useful stuff, but capitalism elicits much more competence in the assembly of not-useful stuff!

And as entrepreneurs become billionaires by hawking this not-useful stuff, we are told, these same entrepreneurs add to “child poverty” and Alabamans “still getting ringworm” by hoarding all the wealth and resources for themselves.

As Ocasio-Cortez added in 2020, the billionaires “made that money off the backs of single mothers, and all these people who are literally dying because they can’t afford to live.”

Human beings are “literally dying” for the reason that billionaires “made that money”? It is no wonder their legacy is tarnished.

Yet there is more to this story. Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci — the scientific married couple who cofounded BioNTech of Germany — became billionaires from developing the first existing COVID-19 vaccine. Noticing this, entrepreneur Louis Anslow tweeted out a Time magazine cover featuring these two, and asked in his tweet, “Are you sure no one deserves to be a billionaire?”

Anslow’s is a worthwhile question. To explore it, this essay comes in two parts. Part One ascertains that there is indeed more that can be said for capitalism and entrepreneurial billionaires than that they “make us stuff.” That many of the free market’s putative advocates tacitly agree with Lindsay Ellis’s belittling of capitalism’s benefits can be inferred from what they have omitted from their “pro”-capitalism statements. What they refrain from stating plainly is that free enterprise — more than any other sort of political economy, socialist or otherwise — has provided the freedom and impetus for innovators to save, lengthen, and enhance human lives. Not just about making us “stuff,” capitalism saves lives. And that is the point that capitalism’s so-called proponents should be emphasizing. If capitalism’s lifesaving nature were obvious to most people, not even an ideologue such as Lindsay Ellis could have been so confident in stating, as a generally accepted platitude, that capitalism is all about producing “stuff” that is “not useful.”

Hence, Part One is a series of over seventeen case studies of this principle in action. Where they are available, the estimated number of lives that a for-profit enterprise saved shall be enclosed. Most of those case studies involve pharmaceuticals and medical devices, but there are other examples that are far less obvious. Electric heating, air conditioners, and even lasers save lives. It was capitalism that facilitated the invention, production, and adoption of these technologies.

Are you sure *no one* deserves to be a billionaire? pic.twitter.com/MYuSzH8TVf

— Louis Anslow (@LouisAnslow) July 27, 2021

Putting all of those case studies in a single blog post takes up a lot of space. Therefore, in this, the shortest version of the essay, I have done the following. This version includes the first two case studies — those of the COVID vaccine and a cancer drug — and then goes to an index of the additional case studies, such as those about implantable pacemakers, MRI scanners, smoke detectors, electric heating, and lasers. That index is followed by the final case study, that of how synthetic nitrogen fertilizer has saved two billion lives.

To Part One, a detractor can reply, “Yes, that entrepreneurs produce medical devices is nice. But as the Earth consists of a fixed quantity of nonrenewable natural resources, it follows that one person owning a billion dollars’ worth of resources means there is less for everyone else. In that respect, if someone invents a life-saving medical device and gains a billion dollars from that, a billion dollars’ worth of resources all going into the possession of this one man still adds to other people’s poverty and the premature death that it brings.”

Such an assumption fails to understand the actual nature of wealth — economic value — and its origin. Consequently, Part Two considers the prospect that there is no inherent limit to the amount of economic value to benefit human beings. Further, insofar as citizens are free and peaceful with one another, someone gains ownership over a billion dollars’ worth of resources to the extent that she created economic value that was of at least that much worth to others. Part Two also summarizes how capitalism contributed to boosting living standards overall, sometimes even in the poorest countries where the government allows for relatively little capitalism. Whereas Part One focuses on specific inventor-entrepreneurs whose efforts have saved lives, Part Two ends with a summary of how peaceable commerce, in total, saves lives on an international scale.

With that, we take a journey into the past two centuries of entrepreneurship and its lifesaving.

The married couple of scientists, Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci, co-founded BioNTech in Germany and partook in a joint venture with the USA’s Pfizer to develop the USA’s first vaccine for COVID-19, one that is an mRNA vaccine. Various attempts have been made to attribute this success more to taxpayer funding than to the couple’s initiative. President Donald Trump tried to take credit for BioNTech’s achievement, proclaiming that it came from Operation Warp Speed, his administration’s program to provide federal funding to synthesize such a vaccine. Yet BioNTech and its American collaborator, Pfizer, did not receive money from this program.

To Part One, a detractor can reply, “Yes, that entrepreneurs produce medical devices is nice. But as the Earth consists of a fixed quantity of nonrenewable natural resources, it follows that one person owning a billion dollars’ worth of resources means there is less for everyone else. In that respect, if someone invents a life-saving medical device and gains a billion dollars from that, a billion dollars’ worth of resources all going into the possession of this one man still adds to other people’s poverty and the premature death that it brings.”

PART ONE: PROFILES OF LIFESAVING FOR-PROFIT ENTERPRISES | ^

Creativity in the Age of COVID | ^The married couple of scientists, Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci, co-founded BioNTech in Germany and partook in a joint venture with the USA’s Pfizer to develop the USA’s first vaccine for COVID-19, one that is an mRNA vaccine. Various attempts have been made to attribute this success more to taxpayer funding than to the couple’s initiative. President Donald Trump tried to take credit for BioNTech’s achievement, proclaiming that it came from Operation Warp Speed, his administration’s program to provide federal funding to synthesize such a vaccine. Yet BioNTech and its American collaborator, Pfizer, did not receive money from this program.

Timothy Springer was another one of those initial investors who placed cash directly into Moderna. As Forbes reports, “Springer was a founding investor of Moderna in 2010, when he put about $5 million into the company. Now, a decade later, that initial investment is worth nearly $870 million.” Langer as well, says Time magazine, was “one of the first” of Moderna’s direct funders. And even before their investments in Moderna, Timothy Springer and Bob Langer engaged in commercial ventures that improved health and human life.

Another lifesaving billionaire is Patrick Soon-Shiong, M.D. This story might seem, at first glance, to be one of taxpayer funding being the lifesaver. But soon Soon-Shiong arrives to provide the twist.

To save space on this blog post, I have put all the other case studies, except the final one, in separate blog posts. Readers can choose for themselves which case studies they will or will not read, according to which sound the most interesting.

* Alex Ulllrich and His Biotech Cancer Treatment

* Herbert Boyer, David Goeddel, and Genetically Engineered Insulin

* Jennifer Doudna, George Yancopoulos, and Gene Editing

* Paul Offit and the Rotavirus Vaccine

* David Hamilton Smith and His Vaccine to Prevent Meningitis

* Wilson Greatbatch, C. Walton Lillehei, and Implantable Pacemakers

* Raymond Damadian and MRI

* Leo Baekeland and Plastics in Hospitals

* Percy Julian, Sr., and New Foam for Fire Extinguishers

* Duane Pearsall and the Smoke Detector

* Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, the Air Brake, and Electric Heating

* Gail Borden and Condensed Milk

* Thomas Midgley and Safer Air-Conditioners and Refrigerators

* Gordon Gould and the Laser

Fritz and His Fertilizer | Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and Synthetic Nitrogen Fertilizer | ^

And, for the last, we have left the biggest lifesaver. Recall that a website frequently cited throughout this essay, ScienceHeroes.Com, was created by Billy Woodward to promote his book Scientists Greater Than Einstein. Although he describes himself as a “businessman” in the About the Author section, the book conveys its author’s unflattering impression of capitalism and for-profit enterprise.

Upon describing an action by Merck that he judges unethical, Woodward hisses that such an action is one “that those teachers who believe in Ayn Rand’s laissez-faire capitalism can teach in business schools and those who revere less the principle of selfishness can explore in ethics classes.” This disparagement is taken farther still on ScienceHeroes.Com.

The book’s final chapter argues that the private sector cannot and will not finance medical research adequately, and therefore there needs to be greater taxpayer funding of science. Woodward frames such “a choice for our future” as one of “Our Health” versus “Our Wealth.”

Yet in totaling the numbers of people saved by scientific projects, ScienceHeroes.Com provides information that is not completely consistent with Woodward’s generally unfavorable estimate of capitalist greed. The scientific endeavor that Woodward’s own website ranks as the one to have saved the most lives is . . . a for-profit venture.

This was the venture by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch in the industrial production of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer. It is well described on ScienceHeroes.Com in two articles penned not by Billy Woodward but by one of the writers assisting him, April Ingram.

Even for reasons other than his commercialism, Haber is not someone who would normally be described as a humanitarian. Prior to the ascension of the Nazis, Haber was a fervent German nationalist, especially in matters of military conflict. During World War One, Haber eagerly assisted the German government in weaponizing chlorine gas to be dispersed on French soldiers. Yet, even considering his role as one of the founders of chemical warfare, Haber instigated a project that holds the record in number of lives saved.

In 1899, the British scientist Sir William Crookes warned that the farms of the West were exhausting all the nutrients of their soil. Soon, they would not be able to grow any more, and the starvation would result. Haber took this to heart. A decade following Sir William’s dire prediction, Haber formulated methods to produce synthetic fertilizer, ammonium nitrate. As an executive of BASF, Carl Bosch refined those methods and applied them on an industrial scale. This became known as the Haber-Bosch process, and it made its namesakes very rich.

Still, the ascension of the Third Reich doomed both these men. Although Haber was a Christian, the Nazis held his Jewish ancestry against him and banished him from practicing any science. This was a crushing blow to someone previously so worshipful of the German state. Bosch went to Adolf Hitler directly to plead on Haber’s behalf. The industrialist informed the führer that purging Jewish scientists would set the country back on physics and chemistry for a hundred years. To that, Hitler simply replied, “Then we’ll just have to work 100 years without physics and chemistry!”

As the Third Reich held a tight grip on the national economy, it was easy for Nazi officials to inflict reprisals on Germans who did not express sufficient enthusiasm for their governance. As Bosch was highly critical of the Nazis, he was gradually stripped of his duties at BASF. Bosch sunk into depression and alcoholism.

Even decades after their death, the process of Haber and Bosch continued to change the world. After the famines imposed by Mao Tse-tung’s communism, China under Deng Xiaoping applied the process and ended the starvation.

ScienceHeroes.Com admits that the for-profit venture of Haber and Bosch has saved “over 2.3 billion lives.” In a Wired article from 2013, Bill Gates informed his readers, “Two out of every five people on Earth today owe their lives to the higher crop outputs” that the Haber-Bosch process “has made possible.”

All of the cases we have studied were about someone becoming obsessed with some problem or mystery and, in an attempt to solve it, exercised creativity in such a manner that resulted in saving people’s lives. This gives the lie to the claim by famous anti-capitalist Noam Chomsky that it takes a “lack of curiosity and independence of mind...” for someone to reach “the high end” of “income distributions...”

A “lack of curiosity and independence of mind” sure does not describe Katalin Karikó, Jennifer Doudna, Percy Julian, Patrick Soon-Shiong, or any of the other innovators who struck it rich.

Value Added to the Natural Resources | ^

The author hopes that by now the reader is convinced that there are many instances throughout modern history of for-profit enterprises contributing to the extension of lives and the comforts within them. Yet those who look askance upon capitalism and billionaires are probably not satisfied. They can proclaim that these instances of lifesaving by billionaires such as Patrick Soon-Shiong and George Yancopoulos do not remove an inherently self-destructive attribute from commercial activity.

It is frequently stated that the global economy runs on nonrenewable natural resources. Such nonrenewable resources include petroleum, coal, tungsten, lithium, and silicon. The total quantity of such resources used as raw materials in goods and services only grows annually. Once these resources are used up, it is said, that will be the end of civilization. The persistence of this belief is a major reason why millions of people nodded in agreement as activist Greta Thunberg went before the United Nations to prevail upon various heads of State to abandon their “fairytales of eternal economic growth.”

The belief also feeds into Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s looking wistfully on the prevailing bias against capitalism that intellectuals had in the period between 1930 and 1979. She longs for a return to that “one point in time” where there was “almost a full consensus among our greatest thinkers in America that capitalism had an expiration date. This Late-Stage Hyper-Capitalism society of ‘just accrue’? This capitalism as an ideology of capital? And that ‘our number-one goal is to maximize profit at any and all human and environmental costs’? They knew that the idea was not sustainable.”

If the amount of wealth and prosperity is nothing more than a direct function of the quantity of nonrenewable natural resources, then the amount of wealth that can be enjoyed does come in a fixed quantity. It may be said that even if Patrick Soon-Shiong’s development of nab-paclitaxel saved the lives of cancer patients, the benefits came at the expense of everyone else in society. The resources that went into fighting metastatic breast cancer, and that went into the big fancy toys that Soon-Shiong and Jonathan Rothberg bought for themselves, are resources denied to everyone else. If Soon-Shiong and Rothberg own and have direct access over a total eight billion dollars’ worth of resources, that is eight billion dollars’ worth of resources less for the rest of Earth’s human population, especially its poorest.

Hence Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez pronounces, “No one ever makes a billion dollars. You take a billion dollars.” (emphases hers).

And she continues that “this system that we live in — life in capitalism — always ends in billionaires. This thing that we live in, starves people.”

To wit, the richer the billionaire is, the more it “starves people.”

That capitalism staves people is an odd claim to the employees of agribusinesses. It would have been news to Carl Bosch.

Yet Dan Riffle, the policy advisor and senior counsel to AOC who stated, “Every billionaire is a policy failure,” reinforces his employer’s zero-sum interpretation. After pretending to understand that more economic value can be created, Riffle makes it known that he will continue to deny, arbitrarily, the logical ramifications of such a fact. That is implicit in his proclamation that “it’s certainly the case that the bigger Jeff Bezos’s and Bill Gates’s slices of the pie are, the smaller everybody else’s slices of the pie are going to be.”

This is the same idea behind Bernie Sanders’s notorious proclamation, “You don’t necessarily need a choice of 23 underarm spray deodorants or of 18 different pairs of sneakers when children are hungry in this country.” Bernie’s presumption is that the resources that went into producing the twenty-three different types of deodorant and eighteen models of athletic shoes were resources that otherwise would have gone into feeding kids starving in the USA. The number of choices in hygiene canisters and fancy footwear is inversely proportional to the ability of America’s youngsters to have enough to eat.

The belief has been expressed by Percy Bysshe Shelley in words that would become cliché soon after they were published: “The rich have become richer, and the poor have become poorer...”

That slogan’s enduring popularity derives from a flagrant misunderstanding of the nature of wealth. The wealth that distinguishes a grand living standard from an inadequate one has less to do with monetary units than with the goods and services for which those monetary units are exchanged. More than that, that wealth is not an inherent function of the quantity of nonrenewable natural resources available. Instead, wealth is in the efficiency of the methods employed to derive life-enhancing value from such resources. It is therefore fitting that the term capitalism comes from “capital,” which has its origin in the Latin capita, meaning “head.” It is fitting because entrepreneurial innovators must use their noggins to conceive and implement such strategies to improve the efficiency by which the natural resources are used.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez blares, “Usually if you’re a billionaire, it means that you control a massive system. It means that you own oil supplies. . . . And to be ethical — if you’re a billionaire today — the thing you need to do is give up control and power” over those resources.

She talks as if petroleum was always inherently worth being in everyone’s control collectively, and then a small cabal of billionaires came and usurped that control all for itself. In reality, the default was a gallon’s worth of crude oil in the Stone Age and even the 1700s was of relatively little advantage to anyone. From the Middle Ages to the eighteenth century, farmers hated it when they found the black sludge. The foul-smelling goop seeped and damaged their crops. The presence of oil on their land only reduced marketplace demand for the property. Striking oil only became a plus and not a minus when Canadian geologist, chemist, and entrepreneur Abraham Gesner discovered and publicized the properties of petroleum that made it an ideal as a source of fuel, one rivaling the utility of whale oil.

That is, a gallon’s worth of crude did not have an inherent value. It gained value subsequent to the fulfillment of two conditions. The first condition was for a scientist such as Gesner to apprehend how that crude oil can be made useful for human beings. And even the fulfillment of that first condition, by itself, was not enough. Once Gesner established that kerosene could be isolated from crude, and that kerosene could light a lamp, that still would not ultimately help anyone who wanted to light a lamp if not for someone bothering to separate the kerosene from the rest of the gunk.

There was nothing obvious about it. That brings us to the second condition that had to be fulfilled for the petroleum to become valuable — someone had to bother undertaking the task of separating the kerosene from the crude and bringing it to market. As anyone with unfulfilled dreams can attest, dreaming up a great plan is a cinch in comparison to following through on it and keeping the commitment. In this instance, someone had to bother setting in motion the separation. That took the planning and organizing conducted by entrepreneurs such as Gesner and George Bissell, and which was taken to a more sophisticated level by John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

PART TWO: HOW, CUMULATIVELY, BILLIONAIRES SAVE BILLIONS OF LIVES | ^

The author hopes that by now the reader is convinced that there are many instances throughout modern history of for-profit enterprises contributing to the extension of lives and the comforts within them. Yet those who look askance upon capitalism and billionaires are probably not satisfied. They can proclaim that these instances of lifesaving by billionaires such as Patrick Soon-Shiong and George Yancopoulos do not remove an inherently self-destructive attribute from commercial activity.

Nor was it obvious to Stone Age people that sulfur could be of use to them. It was a nasty, foul-smelling chemical. It took forward-thinking entrepreneurs to transform such a con into a pro. The German chemist Herman Frasch had such foresight, and developed methods both for pumping large quantities of sulrf from deposits and for extracting the sulfur from crude oil so that kerosene could be refined.

This newly accessible sulfur turned out to be an important ingredient in the first widely used antibiotic, sulfa, which went by the brand name of Prontosil. This medication saved thousands of soldiers’ lives during World War One. As a consequence of Frasch’s achievements, Rockefeller purchased his patents and made him Standard Oil’s director of research. The German’s net worth at the time of his death in 1914 was $5 million, $128 million in 2018 U.S. dollars.

And this principle applies to so much more than petroleum and sulfur.

It was not obvious to the ancient humans who first encountered petrified tree sap that one day it could be placed in telegraphs to have them transmit electrical signals. Nor was it obvious to the first caravans that the sand over which they traveled could be converted into cables that one day would enable one person to communicate instantly to someone else on the other side of the planet. And it was not obvious to the humans who first observed lithium that such a metal would be an excellent conductor in tiny rechargeable batteries powering telephones and computers fitting in their pockets. Nor was it obvious that such a metal one day would be invaluable to keeping hearts pumping, as do the lithium-iodide batteries in Wilson Greatbatch’s implantable pacemakers.

The extension or improvement of life that someone gets out of a good or service is what can be called “economic value.” That is wealth in its most direct form. And this economic value is not fixed and intrinsic to units of natural resources. It is instead to be found in human methods for making use of those resources.

That the the entrepreneur’s planning and coordination of production adds a net increase in value to resources is an important consideration missing from AOC’s tirades. If more than half of the oil resources are controlled by entrepreneurs such as Gesner and Bissell, and later Rockefeller, it is because they are the ones who made the hard choices that gave more than half of the oil resources the value that they have.

And as efficiency improves, a person can obtain just as much — or even more — economic value from a good or service even as smaller quantities of resources need to be used up in the provision of this good or service.

Natural Fact One (of Two): Resource Substitution | ^

Insofar as individuals are free to enterprise peaceably, several facts of Nature guard against the depletion of resources. The first fact is that many different types of resources can be applied for the same use. That means that as one resource used for a particular purpose grows scarcer in current availability, human beings can switch to an alternate resource to substitute it. For much of the nineteenth century, people harvested liquids from sperm whales to light their lanterns. It was as whales grew scarcer and their oil gained in price, that Abraham Gesner discerned that kerosene could be marketed as a cheaper substitute. And copper provides another example.

Since the nineteenth century, copper wire had been used to conduct electricity in telecommunications equipment. It was in telegraph wires and then telephone lines and eventually in satellites. From 1960 to 1969, the price-per-pound for copper climbed, in 2020 U.S. dollars, from $2.83 to $3.35. This motivated firms to search for a cheaper substitute. In 1970, three engineers from Bell Laboratories found it in the form of fiber-optic cables made from glass that itself came from sand. To this day, copper continues to be installed in satellites and other telecommunications equipment, but many parts previously cast from copper have been replaced by the fiber-optics. The inflation-adjusted real price of copper then decreased again. By 1990, copper was priced, in 2020 U.S. dollars, at $2.44.

This ability to make use of substitutes has done well to hold off the depletion of resources.

The excellent 1987 book The Doomsday Myth, by Charles Maurice and Charles W. Smithson, provides case studies of such a phenomenon throughout history. During the 1600s, the British stopped burning wood to heat their homes and opted for coal. In the late nineteenth century America, railroads used less timber for tracks and used more iron and steel. Amid World War Two, the shortage of rubber trees led American engineers to produce synthetic rubber from petroleum. It was also from this book where I learned the details of whale oil being phased out in favor of kerosene to light lanterns.

Even the advent of agriculture illustrates this principle. For ancient hunter-gatherers, the price of food was the hard work it took to hunt and forage. This drove many species to extinction, and led to food shortages. The cheaper substitute was for the farming of grains to become the main source of sustenance.

Interestingly, the real price of copper has again ascended throughout 2021 and 2022. Insofar as engineers are free to innovate, we may again witness engineers devising still other replacements for copper in machinery.

Natural Fact Two (of Two): Greater Utility From Fewer and Smaller Inputs | ^

The economic value that a business produces for its customers is called “output.” “Inputs” refer to the resources that must be used up in the process of generating the output. Inputs include both human labor and the natural resources that the operation entails.

As a firm must trade its own assets to acquire any input, every input adds to the firm’s expenses unless the firm is able to shift such expenses forcibly onto other parties. One example would be for the firm to steal its resources from someone else. That is consistent with the caricature of corporations being evil, but it actually clashes against the very principle of capitalism. Capitalism is contingent upon the enforcement of private property rights. To the extent that a firm coercively plunders someone else, the firm behaves in opposition to capitalism itself. Plunder is stopped to the extent that private property rights — and, with them, capitalism — are enforced consistently. We shall revisit that principle by the essay’s end with respect to pollution and industrial contributions to climate change.

Another method whereby a firm can elude paying the costs of its inputs is for the firm to receive direct taxpayer funding. Insofar as the firm successfully lobbies for this to happen, the firm is redirecting its own expenses onto the taxpaying public. This coercive redistribution is not pro-capitalism nor is this even, as it is often pegged, “pro-business,” “pro-corporation,” “corporationism,” or “corporatocracy.” The costs of a particular business or corporation may be reduced, but this is the result of resources being snatched from the owners of still other businesses and corporations. It is illogical to label this as if it were free capitalist enterprise, as that coercive intrusion leaves those other parties unfree to capitalize on their own enterprise. That is not pro-business any more than the State privileging one human at the forcible expense of another is “pro-human.” In effect, inasmuch as we want businesses to pay their own way, we must oppose direct taxpayer subsidies to them, even ones that perform work as salutary as Moderna’s.

To the extent that people are free and their private property rights are enforced, every input in an entrepreneur’s operations imposes a cost upon that entrepreneur. Thus, the entrepreneur downsizes her costs, and thereby upsizes her profits, insofar as she employs new techniques for producing at least as much economic value as she did before from ever-smaller and ever-fewer inputs of labor and natural resources. And she can also cut costs by producing at least as much economic value from smaller and fewer inputs of tools and machinery. Those tools were created by still other entrepreneurs in prior efforts at coordinating the laborers’ interactions with the natural resources. Hence, everything ultimately comes down to getting more value out of smaller quantities of labor and natural resources.

Since the late twentieth century, this argument has been most commonly associated with economist and business management professor Julian L. Simon, first in 1980 in the journal Science and then more famously in his classic book The Ultimate Resource. However, he was not the first intellectual to advance it. Decades before him in Denmark, from her own research the agricultural economist Ester Boserup induced similar insights. The power of her arguments has been noted even in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). And the general idea behind the argument was advanced over a century earlier by Jean-Baptiste Say in a series of letters he wrote to that prophet of resource depletion, Rev. T. Robert Malthus. These letters were published for the public in 1821.

Such arguments have often been written off by the establishment. But someone co-won the 2018 Nobel Prize in economics for making a very similar case in mathematical form, Paul Romer. Romer is much fonder of taxpayer-funded basic research than Simon was, and there are issues with his presumption that scientific knowledge is a “public good” that cannot and should be privatized. Still, Romer is entirely correct in agreeing that the application of the human mind to improving efficiency in resource usage is the true creator of economic value and that it does the opposite of deplete mindlessly all the Earth’s resources.

Frustratingly, such considerations do little to deter those of a particular political ideology from intoning ominously that the size of the human population will outstrip the Earth’s bounty. These people dismiss, as naïve, the notion that firms can simply boost their profits by improving efficiency and reducing waste. Those people scoff because they grossly underestimate the extent to which, throughout history, such efficiency improvements and waste reductions have been a major source of growth in profits.

A case study of this is to be found in the evolution of electric dynamos. The power plant that Thomas Edison finished constructing in 1882 on Pearl Street in Menlo Park, New Jersey, had six Jumbo dynamos. Each of these dynamos weighed 54,000 pounds and generated 100,000 watts. That is 1.85 watts of electricity generated per pound of machinery. By contrast, a gasoline-powered 10,000-watt dynamo constructed by the firm Briggs and Stratton in 2020 generated 34.7 watts per pound.

Edison’s total investment in the Pearl Street power plant was $600,000. In 2020, U.S. dollars, that comes to $17.28 million. Hence, Edison generating 600,000 watts would cost him, in 2020 U.S. dollars, $28.80 per watt generated. In 2020, an entrepreneur could buy sixty Briggs and Stratton generators, each for $2,000. For that entrepreneur in 2020, generating a single watt of electricity would cost 20 cents.

Here we find that, due to efficiency improvements, a single pound’s worth of material comprising a dynamo in the year 2020 could generate more than eighteen times as many watts in electricity as Edison’s dynamos could, and at less than one percent of the cost.

And that is far from all. Consider the nonrenewable natural resource that is coal. Every few years during the early twentieth century, engineers introduced another model of coal-burning machinery that exerted greater thermal efficiency than did the older models. In the year 1900, more than seven pounds of coal had to be burned to power a 100-watt lightbulb for one hour. By the year 2000, for that same lightbulb to perform that same task required burning less than a single pound.

That principle can be expressed through other figures. Lumens are the units by which light is measured. In the year 1898, one watt powering an incandescent lightbulb would produce six lumens. In 1920, that watt produced ten lumens. In 2003, it would be 200 lumens.

That is less and less coal per lumen.

Recall the point from earlier about Edison’s dynamos. In 1898, a single pound’s worth of Edison’s dynamo would generate 11.16 lumens. By 2003, a single pound’s worth of a Briggs and Stratton dynamo could supply 6,940 lumens. In a little over a century, then, the number of lumens generated by that single pound of material had grown over 600-fold.

Indeed, steel has been used more efficiently over the course of the century. Over 68 percent of the steel put to work in the U.S. economy is recycled annually. When this alloy is newly produced and is being installed for the first time, it is called “virgin steel.” That is treated more economically as well. Steel still goes into automobiles, but not exactly in the same fashion as in previous decades. That is one reason why the weight of automobiles dropped by one fourth between the years 1970 and 2001. For such reasons, between the years 2000 and 2015, even as there was an increase in the quantity of products containing steel, total use of the alloy in the United States fell by 15 percent.

Virgin steel is set to work more efficiently than before and, in turn, it is produced more efficiently as well. Producing steel has always required that iron be heated to the extent that it takes on a molten form. At the opening of the nineteenth century, producers had to burn an average seven tons of coal to churn out a single ton of “blister” steel. This changed in 1856 with inventor-entrepreneur Henry Bessemer introducing the process named for him, wherein cold air would be blasted upon the super-heated iron. Then it took no more than 2.5 tons of coal, in super-heated “coke” form, to finalize a ton of higher-quality “crucible” steel. By the year 2020, putting out that same ton of steel required less than 0.86 tons of coal.

And coal is not the only resource being inputted more economically in steelmaking. Between the years 1930 and 1949, making a single ton of steel cost an average 200 tons of water. That figure decreased to 20 tons by the 1980s. By 2018, the most efficient plants could make a ton of steel from three to four tons. For-profit enterprises have produced technological improvements that conserve water in other aspects as well. Before 1997, the Oberti Olive Plant had to deplete over 10,000 gallons to turn out a single ton’s worth of product. Between 1997 and 2002, the same plant only had to consume 859 gallons to deliver that same ton.

In decades past, the flush of a toilet drained an average 20 liters. In 2018, that same flush drained six liters or fewer.

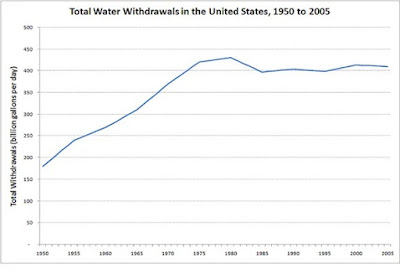

For most of the USA’s history, the total quantity of water used daily steadily increased. But that peaked around the year 1975 at 425 billion gallons per day. From then on, the quantity of water Americans washed down daily remained relatively stable, even as the population and industrial output both grew. From 1984 to 2004, the USA’s per-capita water usage actually dipped by twenty percent.

In the 1970s, every cubic meter of water consumed in Hong Kong generated an average 500 Hong Kong dollars’ worth of economic value. Adjusting for inflation, by the year 2000 that same cubic meter of water yielded twice as much Hong Kong dollars’ worth of wealth. Figures from the heavily populated areas of the United States point to a coinciding trend. In the year 1975, every cubic meter of water inputted for industrial purposes yielded, in 2004 U.S. dollars, an average eight dollars in utility. By 1999, also in 2004 U.S. dollars, that figure doubled.

Gasoline is another nonrenewable input that the market conserves. The inventor and engineer Soichiro Honda, for whom the famous auto company is named, thought that motorists deserved more out of their driving experience. He assembled a team of engineers, including future Honda president Tadashi Kume, to put out a more economical car, the Honda Civic with its CVCC engine. In 1973, before the CVCC engine existed, a motorist could travel 12.9 miles on a single gallon of gasoline. Starting in 1975, upon release of the CVCC, that same gallon would take that same motorist six miles farther. In 2014, that same gallon would take a car farther than 21 miles.

The trend has continued with electric vehicles. When the Tesla Model S came upon the market in 2012, it had a range of 250 miles per charge. By contrast, the Tesla Model S with a Long Range Battery Pack from 2021 had a 390 mile range per charge. Complementarily, in the Nissan LEAF, between 2011 and 2020 the range almost tripled with the number of miles per charge increasing from 73 to 215.

The automobile engines of 2002 were twice as powerful as were those from thirty years earlier. Yet they emitted half as much in exhaust fumes.

Other modes of transportation undergo the same evolution. Compared to one from 1970, a Boeing 747 commercial airliner in 2002 was half as loud and consumed 17 percent less fuel even as it worked at a quarter more horsepower at takeoff. In the duration of 1960 to 1990, the thrust-to-weight ratio in commercial jet engines increased from 4.2 to six. Similarly, between 1940 and 2000, the thrust-to-weight ratio of the gas turbines in these same airplanes lifted from 15 percent to more than 40 percent.

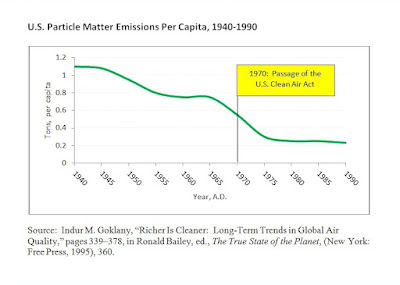

Pollutants that firms release into the air and water are waste byproducts — those are the part of the input that cannot be put into production. As firms gain in efficiency and put every part of the natural-resource input into production, that reduces the waste and therefore reduces the pollution. That is why in both the United States and United Kingdom, firms had been reducing their emissions of toxins in the air even prior to these countries each passing their own particularly strict Clean Air Act.

Insofar as individuals are free to enterprise peaceably, several facts of Nature guard against the depletion of resources. The first fact is that many different types of resources can be applied for the same use. That means that as one resource used for a particular purpose grows scarcer in current availability, human beings can switch to an alternate resource to substitute it. For much of the nineteenth century, people harvested liquids from sperm whales to light their lanterns. It was as whales grew scarcer and their oil gained in price, that Abraham Gesner discerned that kerosene could be marketed as a cheaper substitute. And copper provides another example.

Yes, continue the enemies of capitalism, human being can use their engineering know-how to substitute a scarce resource with a more plentiful one. Still, they ask, how does economics reward entrepreneurs from guarding against the depletion of nonrenewable natural resources on the whole? The answer has to do with the entrepreneurs’ costs being a function of the quantity of natural resources they drain. Thus, we come to the second pertinent fact about preventing the depletion of resources. As humans gain a greater degree of scientific knowledge about their resources, they are indeed able to improve the efficiency of how these resources are expended. And this principle applies even when a more abundant resource cannot be acquired as a substitute for a scarcer one.

↑ Profit = Economic value to customers (Revenue from sale) – ↓ Cost of natural-resource inputs

That involves the development of technologies that improve efficiency.

A doubter might say, “Maybe for every unit of a good produced, less of a particular substance is used. But it doesn’t follow that, in the end, smaller quantities of matter as such are used per unit produced.” Actually, it does follow. That is demonstrated in the reduction of the total mass per unit for particular goods.

A ten-story office building constructed in the year 1999 weighed less than one constructed in 1890. Former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan explains the reasons for this. “Advances in architecture and engineering, as well as the development of lighter but stronger materials, now give us the same working space but in buildings with significantly less concrete, glass, and steel tonnage than was required in an earlier era.”

In 1992, he also noted, “Our radios used to be activated by large vacuum tubes; today we have pocket-sized transistors to perform the same function.” The development of these transistors was responsible for an even more drastic change in the size of computers.

In the 1950s, a mainframe would take up the space of an entire room, sometimes even an entire building. In 2020 U.S. dollars, the cost of assembling and maintaining such a machine was in the millions. A single digital watch today priced at $35 exercises more computing power than did any of those mainframes. A pocket calculator from the year 2000 already computed 350 times faster than did the computers involved in the Apollo 11 mission. Inventor-engineer-entrepreneur Ray Kurzweil makes an even more impressive comparison. He says that in the 1970s, considering the state of technology at the time, it would have taken trillions of U.S. dollars’ worth of resources to build a computer with the same amount of computing power as those of the smartphones that African villagers were carrying around in 2013.

Speaking of mobile phones, from 1990 to 2011, the average weight of one shrank from twenty-one ounces to four ounces. That is, a mobile phone from 2011 was less than one-fifth the weight of one from two deaces prior. Much of this trend has to do with the aforementioned improvements in efficiency of the lithium-ion batteries inside these mobile devices. Between 2008 and 2015, the quantity of kilowatt hours generated per liter of lithium-ion doubled from 200 to 400. And between 2010 and 2017, the quantity of watt hours per kilogram of lithium-ion almost tripled from a little over 100 to 300. Stated in other terms, a mobile phone manufactured in 2015 could perform the same tasks as one from 2008 on just half the amount of lithium.

Using the weight as a proxy in measuring mass, we can discern that a particular product today can produce the same output as that product’s counterpart from decades ago even though the product of today uses up a smaller quantity of mass from natural resources.

That is visible wuth someone we mentioned earlier, that of Jonathan Rothberg and his portable and wheeled MRI machine, the Hyperfine Swoop. Compared to a standard MRI scanner from 1977, Rothberg’s Swoop is ten times lighter in weight and consumes 35 times less energy.

This likewise happens with household tools. The first power drills came out in Germany in 1895. Each weighed seventeen pounds and was only slightly more powerful than a hand-cranked drill. To operate it, someone had to grab its two handles and hold it up to one’s chest. The on-off switch was far away from the machine. To turn it off, the operator had to take his hand off the tool itself. That way, the operator could lose control of the machine and injure himself. In 1917, the American inventors Samuel Duncan Black and Alonzo G. Decker, Sr., introduced a variant that was eight pounds — less than half that of its predecessor — and was easier to use. It had a trigger like a gun that, when pulled, turned the drill on. They priced it at $230, which is over $5,000 in 2020 U.S. dollars.

By 1921, Arno H. Petersen made a version that was still more ergonomic. Instead of putting the trigger where it would go on a gun, Petersen put it on a handle behind the motor. This put less stress on the forearm of the person operating it. And it was four pounds, and sold each unit at $42. That is $609.32 in 2020 U.S. dollars. Petersen’s version, christened the “Hole Shooter,” serves as the general model for those being manufactured in 2022, being roughly the same weight and largely the same in design. In short, the power drills at the time of this writing generate the same output as those from 1895 but are less than a quarter of their weight and sell for less than one percent of their real price.

In 2001, science journalist Ronald Bailey provided other examples of consumers receiving the same or greater economic value from products that consisted of less mass, overall, than did their counterparts from prior decades. That year, food cans were half the weight that they were in 1951. Likewise, plastic soda bottles were only seventy percent the weight of those being sold in the 1970s, and the ones from the 1970s were already lighter than the glass bottles they replaced. And Ronald Bailey returns to our example of copper wire in satellites giving way to fiber-optic cables.

We can dispel any notion that the reduction in the quantity of one category of natural-resource inputs in every unit produced simply shifts to an increased used of a different natural-resource input for that unit. We can do so by examining how much energy altogether is expended on creating an average unit of economic value. This can be done by looking at overall energy intensity. This is how much energy in total — coal, oil, nuclear, and renewables combined — go into the production of economic value. Energy intensity measures the quantity of megajoules that had to be generated to produce an average inflation-adjusted dollar’s worth of economic value. A reduction in the energy-intensity ratio over time means that smaller and smaller quantities of natural resources must be converted into energy to generate the same amount of economic value.

And that is what we find. From 1880 to 2000, the number of megajoules that had to be generated in the USA to bring forth a constant 1990 U.S. dollar’s worth of economic value shrank from 50 to 15. For the United Kingdom in the year 1830, 35 megajoules had to be generated to produce a constant 1990 U.S. dollar’s worth of value. By the year 2000, it was 15.

It may be said that even if a specific unit of a good has shrunk in mass, such as computers getting smaller, the total quantity of natural resources consumed annually has expanded on account of the number of units produced growing annually as well. But, no, the improvements in efficiency have even preempted a major increase in the total quantity of natural resources consumed per year.

Economists calculate the weight of all the goods and services circulating through the U.S. economy. Once again, we use the weight of objects as a proxy in measuring their mass. Alan Greenspan notes that since 1977, the estimated real goods output of the United States annually has maintained a relatively stable weight.

It reached high points of 1.2 billion metric tons in the separate years of 1979 and 2013.

Rockefeller University scholar Jesse Ausubel writes that among 100 commodities studied by Paul Waggoner, Iddo Wernick, and himself, the total annual usage of 36 of them —including steel, timber, paper, asbestos, and chromium — peaked in 1970 and then dropped off since then.

All this happened even as the American economy experienced a net growth since 1979. The increase in wealth is due not to the natural resources themselves as much as how smartly those natural resources are being utilized.

The Carrying Capacity of Land | ^

“That may be all well and nice,” one reply may go, “but there is still an important commodity of which you cannot produce any more units, no matter how cost-effective are. There really is a fixed quantity of land. Its carrying capacity —the number of people who can safely fit on it and live — is finite.” Yet market economics have indeed increased the carrying capacity of that. This is in two respects. First, technological improvements have allowed for a larger number of people to live peaceably on the same square acreage as before. Secondly, the same plot of land can grow greater quantities of food than it has in centuries past.

Let us first begin with how technological innovation has enabled a greater quantity of people to live and work on the same the square footage of land. Throughout the nineteenth century, the U.S. population grew for two reasons. First was the influx of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, masses seeking new opportunity. Second was that the improvements in living standards from industrialization were already beginning to reduce the death rate. Yet this led not to crowding alone but also an increase in the real price of housing. Rents would go up. Entrepreneurs observed that profit was to be made by finding a novel solution to this. It would come in the form of a change in housing itself.

For much of the past several thousand years, human beings had difficulty with high-rises. And that was with good reason. Most buildings were structures supported by their outer walls. The taller the structure was, the greater a burden the structure put on its base. The base had to be the widest section, much wider than the building’s top. Hence, most tall artifices, be they in Egypt or in Mesoamerica, had to be constructed in the shape of pyramids. The walls having to be wide reduced the space on the interior, and there was less interior space still near the top of the structure.

This was dealt with in the late nineteenth century. This was when, due to greater economic freedom than in centuries past, such figures as George Westinghouse and John D. Rockefeller, Sr., thrived. It was this environment that created opportunities for a pioneer in the designing of skyscrapers, William LeBaron Jenney.

One day upon looking at his wife’s bird cage and the bars on the outside, inspiration breathed new life into Jenney. Limitations were placed on a building’s height exactly because of how architects had traditionally relied on the outer walls supporting the structure. Instead, Jenney reasoned, the structure should be supported by a metal frame — a sort of skeleton — inside the inner walls. The construct, then, would not need to be pyramid-shaped; the highest story could be just as spacious as the lowest.

This greatly increased the carrying capacity of land. As noted by London’s Economic Development Office, “Accommodating the same number of people in a tall building of 50 stories as in a large building of five stories requires roughly one tenth of the land.”

Many great technologies enabled farmers to grow more food per acre of earth. From 1950 to 2001, corn yields per acre in the United States tripled.

Improved Productivity Helps People on the Lower Income Distribution | ^

Citing a 2004 study by Erik Rauch at MIT, utilizing U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data from 1947 to 2000, Silicon Valley tech writer Andy Kessler observes that by the year 2000, someone would only need to work eleven hours a week to attain the equivalent value of what someone earned from a full forty-hour work week in 1950. To put it into perspective, Kessler writes that “we could have knocked 30 minutes off the average work week every year since 1950” and by the year 2000, “still maintained our 1950 standard of living.”

And, indeed, even as lithium is employed more efficiently in machines, its real price keeps falling. Between 2010 and 2019, its price per kilowatt hour in 2019 U.S. dollars descended from $1,183 to $156. In nine years, that was a more-than-fivefold decrease.

A copper wire can transmit 24 voice channels or about 1.5 megabytes of information per second. Far thinner and lighter optical fiber can transmit more than 32,000 voice channels and more than 2.5 gigabytes of information per second. The first American communications satellite, Telstar 1, was launched in 1962 and could handle 600 telephone calls simultaneously. Modern Intelsat satellites can handle 120,000 calls and 3 TV channels at the same time.

Alan Greenspan observes that this even happens with our clothing. “The development of the insights that brought us central heating enabled lighter-weight apparel fabrics to displace the heavier cloths of the past.”

It reached high points of 1.2 billion metric tons in the separate years of 1979 and 2013.

“That may be all well and nice,” one reply may go, “but there is still an important commodity of which you cannot produce any more units, no matter how cost-effective are. There really is a fixed quantity of land. Its carrying capacity —the number of people who can safely fit on it and live — is finite.” Yet market economics have indeed increased the carrying capacity of that. This is in two respects. First, technological improvements have allowed for a larger number of people to live peaceably on the same square acreage as before. Secondly, the same plot of land can grow greater quantities of food than it has in centuries past.

And the result of all the aforementioned entrepreneurial ingenuity has been improved living standards. Moreover, with the exception of one category of product we will discuss later, this has led a reduction in real prices over most consumer goods, especially food.

Here we must emphasize the distinction between nominal prices and real prices. Nominal prices are the price of a product taken at face value. A candy bar priced at two cents in 1904 was 44 cents in 2009. The nominal price in the latter year was twenty-two times that of the former year.

The main cause of inflation is the U.S. Treasury and U.S. Federal Reserve putting more and more monetary units in circulation. When the quantity of monetary units increases at a rate that exceeds that rate at which the quantity of goods and services increases, that is more monetary units chasing after the same goods and services. Vendors have to raise the nominal prices of their goods; otherwise, there will be a shortage. This inflation hurts most the parties that are living on savings and fixed incomes, such as senior citizens collecting their retirement. That is why policymakers should listen to free-market advocates concerned about the Treasury and the Fed devaluing the currency. But that is another essay for another time.

Germane to this particular essay, because inflation obscures actual changes in prices, we need another metric by which to judge the extent to which prices have changed over the decades. Many economists rely on something called the “consumer price index” in order to measure inflation. With it, they calculate how much economic value a U.S. dollar from today could have purchased in past years, be they 1930, 1940, or 1950, and vice versa. What a single nominal U.S. dollar could purchase in 1900, for example, was the equivalent of what a nominal $31.10 could purchase in 2020. A price that is calculated to account for inflation is known as “real price.”

Economist W. Michael Cox, formerly of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, has another approach. He asks his fellow citizens to consider the average amount of time someone had to spend at work in order to purchase a particular good.

By that standard, the trend has been for important goods to get cheaper and cheaper. For someone in the year 1930 to afford 100 miles’ worth of air travel, that person would have to do the equivalent of twelve hours and 46 minutes’ worth of work. By 1990, one could purchase that same 100 miles of air travel by working one hour and two minutes. In 1900, affording 100 kilowatt hours of electricity would entail working for 107 hours and 17 minutes. By 1990, that quantity could be earned by spending 43 minutes at work.The same trend is seen with food. In 1940, a person had to spend one hundred hours on the job to be able to purchase a three-pound chicken. By 1990, that chicken could be purchased after spending fewer than twenty minutes. The downward trend in prices here cannot be attributed properly to federal legislation such as the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. The price of chicken was already falling. Between 1900 and 1930, the number of hours one had to labor to obtain this three-pound chicken fell from 160 to 110.

For many consumer goods today, a single hour of work will buy for someone in the First World a larger quantity of theese consumer goods than that same hour of work would have fetched for any previous generation. That is a net gain in wealth for everyone in the First World.

In the United States, a household falling under a certain income threshold puts it under the official federal poverty line. Whether the household is in poverty is calculated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services according to the household’s income and the number of people living in it. As of this writing, a family of four is under the poverty line if it brings in less than $26,500 annually. Even many households under this poverty line provide evidence of how living standards improve to the extent that people are free. In 1950, fewer than 80 percent of all U.S. households possessed a refrigerator. By 1997, a refrigerator was in 90 percent of U.S. households falling under the federal poverty line.

Goods That Have Not Decreased in Real Price | ^

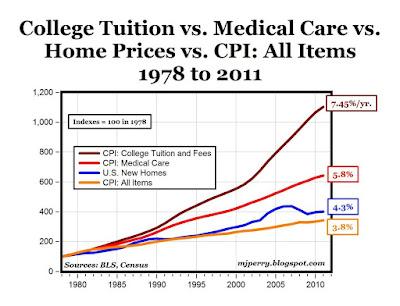

The general trend for units of consumer goods is not only for smaller quantities of natural resources to be inputted into their creation but also for them to decrease both in real cost for the manufacturers and real price for consumers. All these reductions are the consequence of improved industrial efficiency. Yet one may notice that the general price decreases do not apply to most of the pharmaceuticals and medical devices I mentioned in Part One of this essay. Genentech’s human insulin reduced costs for producers but it did not substantially shrink in real price for diabetic patients. Nor were there big price reductions in cancer drugs after the release of those from Patrick Soon-Shiong and Axel Ullrich. That is because, sadly, there is one large, general category of product to which the reductions in real price have not applied. This is actually not a failing of laissez-faire free market principles, however.

The products that have not decreased, but which instead have often increased, in real price include health care, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, higher education, and residential homes. What these goods and services have in common is how much of a financial commitment they all are. And they have something else in common. It is that the federal government has instituted measures to help people obtain cash or credit to procure these goods and services. Medicare and Medicaid assist in paying for health care, prescription drugs, and medical devices. Federal loans assist in obtaining higher education and housing — two goods so great in expense that they are paid for in installments.

These are taxpayer subsidies. Even if the borrower pays back the federal loan’s principal plus interest, there remains, on a net balance, a taxpayer-funded payment to the borrower. The reason for that is that the interest rate the federal government charges is always less than the interest rate that would have been charged by a privately owned lending institution. The difference between the government’s and the private lenders’ interest rates is absorbed by taxpayers.

What happens is as follows. First, a particular good in this category is considered too costly. The government then provides taxpayer subsidies to assist in purchasing these goods. However, this raises demand, and the providers of these goods respond to this rise in demand by raising prices. Paying for real estate grows more daunting, as it does with university tuition. As these prices ascend, activists and the general public clamor for larger subsidies to cover these new higher prices. Taxpayer subsidies purported to make a particular good more affordable therefore ultimately make that good more expensive.

Although other writers such as economist Richard Vedder have described this phenomenon before he did, Robert W. Tracinski gives an apt name for this — the Paradox of Subsidies.

Laissez faire is not to be blamed for this predicament. Nor does it follow that these goods and services would not decrease in real price if none of the taxpayer subsidies existed. Cosmetic surgery and LASIK eye surgery, for example, are not covered by health insurance or taxpayer subsidies. Exactly for that reason, such procedures have plunged in real price over the past 15 years.

Recall that throughout the 1950s, Percy Julian was able to reduce the price of progesterone tenfold. By contrast, the legislation in 2006 to ensure that Medicare pay for prescription drugs has only driven up the real price of medication.

Food purchases are also subsidized in the form of food stamps, now called the supplemental nutritional assistance program (SNAP). But all of those who are concerned about food prices should be thankful that these subsidies go to a minority rather than the majority of the population. If the vast majority of Americans paid for their sustenance with SNAP, the real prices of food would be steadily increasing as well.

Laissez faire not being the culprit for the rising real price of taxpayer-subsidized goods, we see that in areas where markets are freer, the freedom of enterprise to improve efficiency has shrunk the quantity of natural-resource inputs used and has lowered real prices for goods and services.

The Poor Get Richer | ^

Yet most of the world’s human population persists in being poorer than it should be. As discussed earlier, there are still many casualties from people breathing — as they try to keep warm — the fumes rising from their fireplaces. The main reason for the holdup in development is that most countries have kleptocratic governments. People practice commerce but their governments usually refrain from protecting them from theft. Often on a whim, the State itself will seize the people’s meager belongings. But as to the extent that they have experienced any liberalization, such as the country becoming more open to international trade and direct investment, the perks of liberalization have conferred improvements in living standards upon the developing world’s residents.

Consequently, average living standards have climbed in both the rich countries and the developing ones over the past half-century. It is here often interjected that the statistical mean, the average among all the numerical figures, is not always the statistical mode —the numerical figure that, among all the cases, recurs most often. If the mean global annual income shot up, what if all the gains went to the wealthiest one percent of the population? Maybe inflation-adjusted incomes for everyone else has remained the same or fallen? The economists David Dollar and Aart Kraay looked into this. They found, “When average income rises, the average incomes of the poorest fifth of society rise proportionately.” A trio of academic economists led by John Luke Gallup had a corroboratory result. They discerned “a strong relationship between overall income growth and real growth of the income of the poor.”

We can gain insight into these changes by observing what the United Nations defines as life-threatening absolute poverty. Someone falls under that threshold if that person makes less than $1.90 per day in inflation-adjusted 2019 U.S. dollars. This should not be confused with the U.S. federal government’s criterion for falling under the country’s official poverty line. Someone can be under the U.S. poverty line but still be out of absolute poverty by the U.N.’s standard.

Overall, the rate of life-threatening absolute poverty has been slashed, even in the developing countries. Between 1981 and 2008, the share of the global human population in life-threatening poverty dropped from 52 percent to 22 percent. That is a figure sliced by more than half.

And China’s ascension to wealth is not sufficient to explain this decline. Professor Max Roser of Our World in Data scrutinized what the results were when China was excluded. In 1981, 29 percent of the non-Chinese human population was in absolute poverty, whereas in 2013 the figure was 12 percent. For such reasons, Georgetown University economics professor Steven Radelet finds it necessary to emphasize that the “improvements” in living standards among the developing countries “go well beyond China.”

Many find it tempting to attribute this poverty reduction to taxpayer-funded foreign aid and to charitable NGOs. They have played a role, but as U2 front man Bono notes, something else has more to do with it. “Commerce — entrepreneurial capitalism,” he told an auditorium of Georgetown University students, “takes more people out of poverty than aid.” The data corroborate Bono’s assessment. Columbia University’s Howard Steven Friedman inquired into how much, between the years 2000 and 2013, the taxpayer-funded U.N. Millennium Development Goals (MDG) had to do with the developing countries’ gains in living standards.

It turns out the MDG had very little to do with the improvements; it was mostly for-profit commerce and private charity. In the few cases where some taxpayer-funded government project helped, such as with the construction of municipal roads, that came from municipal government and municipal taxation, not taxpayer-funded aid from the rich countries.

The World Bank does not attribute trade as the prime reason for the poverty reduction, but the trade does contribute to what the World Bank determines is the prime reason. As the World Bank explains, “the creation of millions of new, more productive jobs, mostly in Asia, but also in other parts of the developing world, has been the main driving force” behind the fact that “poverty has declined in the developing countries.” After all, “the private sector is the main engine of job creation and the source of almost 9 of every 10 jobs in the world.”

Among those jobs are those that capitalism’s detractors have reviled as exploitation. These would be initially low-paying jobs in factories established through foreign direct investment, factories often derided as “sweatshops.” From the 1950s onward, Asians opted for these sweatshops in the city because they paid two to three times as much as those in the village or country. Contrary to modern assumptions, in countries that are more politically liberalized we find that the trend is not for the majority of the workforce to be stuck in low-paying drudgery for decades on end. Reason magazine has profiled a factory in Taiwan that, during the 1970s, manufactured Barbie dolls. The workers in such factories saved their money and sent their children to schools to hone other skills. That is how countries such as Japan and Taiwan arose from destitution to First-World affluence. A similar phenomenon took off in India in the early 1990s with its deregulation of information technology.

The World Bank’s 2013 findings on poverty reduction corroborate Ayn Rand’s observations from over three decades earlier. She already noted that insofar as it has been implemented, capitalism has “raised the standard of living of its poorest citizens to heights no collectivist system has ever begun to equal, and no tribal gang can conceive of.” For such reasons, Rand related elsewhere, “If capitalism had never existed, any honest humanitarian should have been struggling to invent it.”

Although she did not know about him as she wrote those words, Ayn Rand seems to be anticipating the epiphany that Bono has had about global economics. Taking his Catholicism seriously, Bono had always concerned himself with the plight of the poor. When he first rose to fame in the 1990s and exercised his celebrity status to bring attention to this plight, he originally went by the conventional interpretation of capitalism being evil. One day at a conference, he met African development economist George Benjamin N. Ayittey, who implored him to consider it from another angle. As Bono observed over the decades which antipoverty measures worked and which did not, it was exactly his concern for the well-being of the poor that his impressions about capitalism had changed. He imparted to Rolling Stone magazine, “If you told me twenty years ago that commerce took more people out of poverty than aid and development, I’d have scoffed.” He is not scoffing anymore. Instead, he laughs in his speech to the Georgetown students, “ ‘Rock star preaches capitalism.’ Wow! Sometimes I hear myself, and I just can’t believe it!”

We often hear that capitalism must be fought by antipoverty programs. Yet capitalism is the antipoverty program.

That cliché that Percy Bysshe Shelley popularized about the rich causing the poor to become poorer is economically illiterate. To the extent that people are free to enterprise, the rich get richer and the poor get richer.

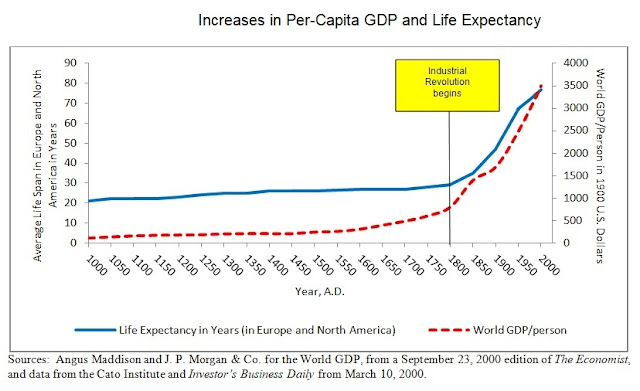

From the relative liberalization in the nineteenth century, and as a result of its consequent Industrial Revolution, the average lifespan in the United Kingdom, Western Europe, and North America ascended from 27 years in 1800 to 77 years by 1988. Starting in the late twentieth century, the developing countries began to experience comparable effects to the extent that they have been exposed to the gains of liberalization.

Georgetown University economist Steven Radelet points out that between 1980 and 2015, “the rate of child death has declined in every single developing country in the world where data are available. There are no exceptions” (emphasis Radelet’s).

And, as Max Roser notes at Our World in Data, the boost in average lifespan is due not only to reductions in the infant mortality rate. Thus, contrary to the final chapter of the book ScienceHeroes.Com was created to advertise, there is no conflict between “Our Health” and “Our Wealth.” Each of those reinforces the other.

Throughout Part One, we learned of how illustrious entrepreneurs organized the creation and distribution of specific products that saved lives. Here, in Part Two, we begin to see how all those efforts add up.

What Capitalism Can Do for the Climate | ^

For the purpose of saving space, I have relocated this section of the essay to this separate blog post. The bottom of that blog post has a link to return to this one.

Capitalism Vs. Hunter-Gatherer Life Vs. Socialism | ^

No, insist detractors. In lieu of just developing new technologies to continue with man’s consumption of resources, they declare, everyone should just learn to live on less —especially the vendors of the world. Anti-capitalists see vendors such as Wilson Greatbatch not as wizards who enrich others through their inventiveness as much as they see them as predators who extract money from customers.

These anti-capitalists remember a time in their childhoods when their parents or guardians provided the amenities. As adults, these anti-capitalists yearn for the presence of some still-higher-ranking parental figure who can bail out adults in their desperate hours. They remember stories of how human beings once had the abundance of the Garden of Eden, only to lose it. Upon being banished from paradise, human beings were thereafter doomed to mortality and the need to struggle for sustenance. No matter the net increases in global economic value provided by the George Westinghouses and Wilson Greatbatches of the world, they will never measure up to the standard set by Eden.

But the reality is reverse. The abundance of the Garden of Eden was never the default. Rather, the default has always been life-threatening poverty. Industrialization and capitalism “did not create poverty,” Ayn Rand elucidates. They “inherited it.” More than that, as we have seen, it is industrialization and capitalism that have done the most to alleviate this penury.

Socialism has over a century of promising that Edenic plenty, of all customers getting everything they need. And socialism has failed for that more-than-a-century, performing worse than whatever amount of capitalism has existed. Yet in its constant false promises, socialism continues to be hailed as more desirable than capitalism.

Such considerations are denied by various opponents of capitalism. Propagandist Michael Perelman huffs about private ownership of agricultural land replacing the practice of shepherds grazing their flocks on the medieval commons. Others go back even farther in time. They cite the living conditions of hunter-gatherers as far better. Many of the lifesaving innovations profiled in Part One were a remedy to dangers imposed by previously established technologies. George Westinghouse’s air brake cut the number of railroad fatalities, but there would never have been a need for this air brake if locomotives were never invented. Electric heating that Westinghouse helped make possible has saved people from having to damage their lungs in the employment of fireplaces. But people would not have suffered from this indoor air pollution if no houses were built. After all, for most of the species’s history, hunter-gatherers have managed to live without skyscrapers, houses, or cabins.