Just as George Westinghouse availed to people a safer way to protect themselves from the cold, Thomas Midgley availed to them a safer way to protect themselves from the heat. He did this through his improvements to air conditioning and refrigeration.

Sunday, March 27, 2022

Thomas Midgley and Safer Air -Conditioners and Refrigerators

Stuart K. Hayashi

Just as George Westinghouse availed to people a safer way to protect themselves from the cold, Thomas Midgley availed to them a safer way to protect themselves from the heat. He did this through his improvements to air conditioning and refrigeration.

Attempts to control the temperature and air quality had been attempted before. In Florida in 1851, a medical doctor named John Gorrie had been treating fever in malaria patients. He invented an ice machine for cooling the room. It brought in air and compressed it. The air then ran through pipes, cooling as it expanded before reaching the patients. For this, newspapers denounced him and his invention as unholy. They considered it “natural” and God’s plan for people to bear the heat of the day. For Dr. Gorrie to help people avoid that was an unnatural tampering with nature and God’s will. Such thinking had long predated similar fears of genetic engineering.

When air conditioning was refined and made more sophisticated decades later, it was to address the problems connected to a particular type of heat — humidity. And this was not for general consuming public but for industrial applications. The concerned businesses were not as interested in doing anything about dry heat.

Although more strongly associated with a contraption that Willis Haviland Carrier assembled in 1902, the term “air conditioning” was coined four years later by Stuart W. Cramer, Sr. He had been designing and running cotton mills throughout North Carolina. Inspecting them, Cramer observed that in greater humidity, his mills’ wheels spun faster. He was resolute in hitting upon some configuration by which he could control the humidity to ensure that the wheels would rotate at the most consistent and convenient rate.

Air conditioning involves liquefied or gasified chemicals flowing through a box and warming or cooling the air inside it. A fan blows the treated air out of the box and to where the cooled or warmed air is desired. Use of gasified or liquefied chemicals flowing through tubes to control the temperature is also the principle behind refrigeration. In Cramer’s case, moisture was added and the vents blew moistened air throughout the mills.

Four years earlier in New York state, twenty-five-year-old Willis Carrier had been mulling over the opposite objective — how to remove moisture from the air. The Sackett and Wilhelms Lithography and Printing Company attempted to print newspapers in a multi-color format. It did so by a laborious process of one color at a time, whereby ink of that color was added in a single layer. In order for the page to be colored as planned, every application of a layer of ink had to align precisely with the others. Yet the humidity had unpredictable effects on the paper, which shrank or expanded in odd fashions. As several layers of different-color ink were added, the final result was a distorted image. To do something about the humidity, Sackett and Wilhelms went to Carrier’s employer at the time, the Buffalo Forge Company.

As Carrier’s invention blew temperature-controlled air through its vents, causing the air to circulate, metal plates inside of the machine collected and trapped the water droplets that had been circulating.

In 1915, Carrier left Buffalo Forge to start his own company, taking several other Buffalo Forge engineers with him. He had heard of Stuart Cramer’s speech from nine years earlier and adopted the term “air conditioning” for the name of his own company. He had credited Cramer as an inspiration for several ideas he was putting into practice. Carrier’s air conditioning gained greater recognition and appreciation when installing it in movie theaters during the summers of the Great Depression. Gradually, over time, the general public came to accept air conditioning, forgetting the crowing from decades past about how this technology was unnatural and sacrilegious.

Both Carrier and Cramer enjoyed commercial success. Once Edison and Westinghouse had established the technology, Cramer would go on to build several power plants that provided Texans with electric heating and thereby liberated them from the indoor air pollution that came from fireplaces. In this manner, Cramer protected customers from both the heat and the cold.

From these enterprises, Cramer had amassed enough cash that his descendants would be prominent figures of high society. His grandson, Stuart W. Cramer III, invested the inheritance into oil and competed with Howard Hughes for the romantic affection of not one but two Hollywood actresses — Jean Peters and Mighty Joe Young star Terry Moore.

Even as Carrier enjoyed success, there remained a tremendous disadvantage with air conditioners and refrigerators — the gases and liquids inside of them released fumes that were toxic to those who handled them. These gases and liquids were even flammable. They had caused fires that proved to be fatal. This problem was finally rectified in 1950 by a General Motors engineer in Ohio named Thomas Midgley.

If you run a quick Google search this instant on Thomas Midgley, in the results you will find that the man is routinely denounced as misguided at best and evil at worst. He invented leaded gasoline, which proved to be a major toxin. It usually goes unmentioned that Midgley’s work on air conditioning and refrigerants, which is demonized even more ferociously, has actually saved many lives.

At General Motors, Midgley reported directly to multimillionaire Charles F. Kettering, the engineer who invented the modern automobile’s self-starter. Kettering is the reason why car engines today turn on with a turn of the key. GM spun off a subsidiary company, Frigidaire, to refine air conditioners and refrigerators. Such technologies were connected due to GM’s interest in providing air conditioning in its vehicles.

Although leaded gasoline ended up being poisonous, in 1928 Midgley was genuinely interested in finding a technique to produce air conditioners and refrigerators that would not harm their users.

With two assistants, Midgley examined a pocket-sized periodic table. He knew the properties that were needed. Besides being nontoxic and nonflammable, it had to be stable with a boiling point within 0 to -40 º C. The element fluorine would work well except that it was toxic. He thus considered whether the fluorine could be rendered safe if it was bonded to some other elements to form a new compound. After all, hydrogen is dangerous all by itself as an element, but a reaction between two hydrogen atoms and a single oxygen atom results in relatively safe H2O. Likewise, fluorine would be rendered safe if bonded with chlorine and carbon. The seeming answer to the problem was CFCs — chlorofluorocarbons, with which GM tagged the brand name “Freon.”

Still, there was an issue of whether it might turn out later that CFCs did not function as well as they seemed. Hence, General Motors had a backup. Midgley and his team also considered another class of compounds — hydrofluorocarbons, or “HFCs” — that potentially bore the same beneficial qualities as CFCs without the same drawbacks. If ever there was an unforeseen problem with CFCs, then HFCs might serve as a replacement.

Because the gases in air conditioners and refrigerators had earned a reputation for being health hazards, in 1930 Midgley publicly demonstrated the relative safety of Freon. He lit a candle near the liquid. He boiled it in a bowl and inhaled the gases emerging from it. Then he blew the candle out. This presentation ended the public’s reluctance to purchase the new safe refrigerators and air conditioners.

Decades following Midgley’s death, other scientists discovered that sulfur dioxide emissions from the use of CFCs entered the Earth’s atmosphere and depleted the ozone layer. The federal government passed laws to phase out CFCs in the ensuing years. Yet, as science journalist Sharon Bertsch McGrayne notes, the HFCs that became the replacement in air conditioners and refrigerators in the 1990s were “all substitutes discovered by Midgley and his colleagues.”

In recent years, the HFCs have been blamed for posing yet another dilemma. Although they do not have the same effect on the ozone layer, they still contribute to greenhouse warming. Besides his invention of leaded gasoline, this is the other reason that Midgley has become widely denounced all over internet. For such reasons, it appears Pope Francis has revived the idea that this technology is sinful. He intones that the “growing ecological sensitivity” he desires in people still “has not succeeded in changing” the world’s most “harmful habits of consumption... A simple example is the increasing use and power of air-conditioning.” This is a vice that the pontiff deems “self-destructive.”

How capitalism itself can address the issue of greenhouse emissions from air conditioners and other machinery is a matter to which we shall revisit in Part Two.

With the public not yet conscious of ozone depletion or anthropogenic climate change, Midgley rendering air conditioners and refrigerators safe — at least in terms of coming into direct contact with them and handling them — was a boon to GM. This success had made Midgley a multimillionaire.

He was not able to enjoy his new wealth as much as he expected. Beginning in 1940, he was stricken with polio. He underwent intense physical therapy regularly in a swimming pool but he remained paralyzed from the waist down. Throughout his mansion, he set up a system of ropes and pulleys to help him go about independently. Yet one day his wife found him dead, strangled by these same hoists.

Many of the websites condemning Midgley frame this death as a fitting metaphor for the man’s life — Midgley was killed unexpectedly by one of his own inventions, just as he lacked the foresight on how his more-famous inventions would kill others.

Representative of this schadenfreude is YouTube presenter Matthew Santoro, who generally holds a reputation for being a nice guy. He cracks to his audience, “And I know a lot of you right now are like, ‘Aw, it should’ve been the lead poisoning that got him. That would’ve been poetic justice.’ And, to those of you, I say, ‘You’re kind of sick — and right.’” Yet chemistry professor and historian Carmen Giunta observes that Midgley’s own family and loved ones had concluded that Midgley had committed suicide with these ropes. The reason that they let the media report that this was an accident was that persons who killed themselves were stigmatized even more severely back then. By comparison, allowing the public to interpret Midgley’s death as an accident was to save face.

Furthermore, what is usually glossed over is that Midgley’s innovations in air conditioning and refrigeration saved lives very directly. This can be observed in the changes in heat-related mortality in Chicago over the course of a century. In 1901 in the windy city, there were 10,000 heat-related deaths. In 1955, that figure had dropped to 885. In the heat wave of July 1995, it was 300.

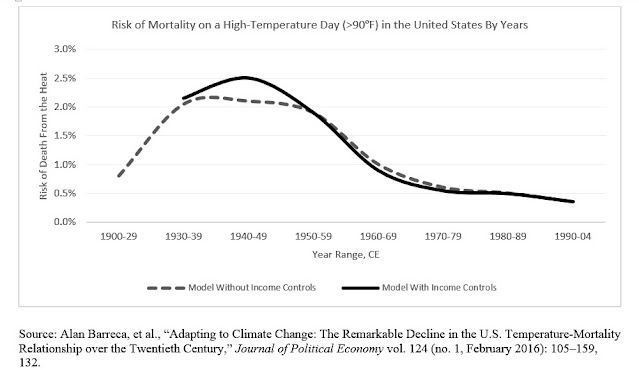

In 2016, a team of scholars including Carnegie Mellon economist Karen Clay published a scientific assessment of heat-related mortality in the United States throughout the twentieth century. The team found that between 1940 and 2004, the statistical risk of dying from heat in the USA on a day of over-90-º-F temperatures had fallen by over 60 percent. Between 1930 and 2004, the risk of dying from the heat on over-80-º days reduced by three quarters. And what was the major reason for this reduction? The team admits that the adoption of “residential air conditioning explains essentially the entire decline in hot day–related fatalities.”

It is fortunate, then, that this technology has become increasingly affordable to those of lower income. In 1950, less than 18 percent of all U.S. households could access this technology. By 1997, over 68 percent of U.S. households below the official federal poverty line now had air conditioning. By 2005, among those under the federal poverty line, it was over 77 percent.

Midgley has much to do with how, as was said by Aperion Care and as was published on the World Economic Forum’s website, 2 million lives have been spared of heatstroke from 1950 onward.

Just as George Westinghouse availed to people a safer way to protect themselves from the cold, Thomas Midgley availed to them a safer way to protect themselves from the heat. He did this through his improvements to air conditioning and refrigeration.