The Two-Blog-Post Version: Blog Post 2 of 2

Table of Contents

PART TWO: HOW, CUMULATIVELY, BILLIONAIRES SAVE BILLIONS OF LIVES

* Value Added to Natural Resources

* Natural Fact One (of Two): Resource Substitution

* Natural Fact Two (of Two): Greater Utility From Fewer and Smaller Inputs

* The Carrying Capacity of Land

* Improved Productivity Helps People on the Lower Income Distribution

* Goods That Have Not Decreased in Real Price

* The Poor Get Richer

* What Capitalism Can Do for the Climate

* Capitalism Vs. Hunter-Gatherer Life Vs. Socialism

CONCLUSION

PART TWO: HOW, CUMULATIVELY, BILLIONAIRES SAVE BILLIONS OF LIVES | ^

The author hopes that by now the reader is convinced that there are many instances throughout modern history of for-profit enterprises contributing to the extension of lives and the comforts within them. Yet those who look askance upon capitalism and billionaires are probably not satisfied. They can proclaim that these instances of lifesaving by billionaires such as Patrick Soon-Shiong and George Yancopoulos do not remove an inherently self-destructive attribute from commercial activity.

It was not obvious to the ancient humans who first encountered petrified tree sap that one day it could be placed in telegraphs to have them transmit electrical signals. Nor was it obvious to the first caravans that the sand over which they traveled could be converted into cables that one day would enable one person to communicate instantly to someone else on the other side of the planet. And it was not obvious to the humans who first observed lithium that such a metal would be an excellent conductor in tiny rechargeable batteries powering telephones and computers fitting in their pockets. Nor was it obvious that such a metal one day would be invaluable to keeping hearts pumping, as do the lithium-iodide batteries in Wilson Greatbatch’s implantable pacemakers.

The extension or improvement of life that someone gets out of a good or service is what can be called “economic value.” That is wealth in its most direct form. And this economic value is not fixed and intrinsic to units of natural resources. It is instead to be found in human methods for making use of those resources.

That the the entrepreneur’s planning and coordination of production adds a net increase in value to resources is an important consideration missing from AOC’s tirades. If more than half of the oil resources are controlled by entrepreneurs such as Gesner and Bissell, and later Rockefeller, it is because they are the ones who made the hard choices that gave more than half of the oil resources the value that they have.

And as efficiency improves, a person can obtain just as much — or even more — economic value from a good or service even as smaller quantities of resources need to be used up in the provision of this good or service.

Natural Fact One (of Two): Resource Substitution | ^

Insofar as individuals are free to enterprise peaceably, several facts of Nature guard against the depletion of resources. The first fact is that many different types of resources can be applied for the same use. That means that as one resource used for a particular purpose grows scarcer in current availability, human beings can switch to an alternate resource to substitute it. For much of the nineteenth century, people harvested liquids from sperm whales to light their lanterns. It was as whales grew scarcer and their oil gained in price, that Abraham Gesner discerned that kerosene could be marketed as a cheaper substitute. And copper provides another example.

Since the nineteenth century, copper wire had been used to conduct electricity in telecommunications equipment. It was in telegraph wires and then telephone lines and eventually in satellites. From 1960 to 1969, the price-per-pound for copper climbed, in 2020 U.S. dollars, from $2.83 to $3.35. This motivated firms to search for a cheaper substitute. In 1970, three engineers from Bell Laboratories found it in the form of fiber-optic cables made from glass that itself came from sand. To this day, copper continues to be installed in satellites and other telecommunications equipment, but many parts previously cast from copper have been replaced by the fiber-optics. The inflation-adjusted real price of copper then decreased again. By 1990, copper was priced, in 2020 U.S. dollars, at $2.44.

This ability to make use of substitutes has done well to hold off the depletion of resources.

The excellent 1987 book The Doomsday Myth, by Charles Maurice and Charles W. Smithson, provides case studies of such a phenomenon throughout history. During the 1600s, the British stopped burning wood to heat their homes and opted for coal. In the late nineteenth century America, railroads used less timber for tracks and used more iron and steel. Amid World War Two, the shortage of rubber trees led American engineers to produce synthetic rubber from petroleum. It was also from this book where I learned the details of whale oil being phased out in favor of kerosene to light lanterns.

Even the advent of agriculture illustrates this principle. For ancient hunter-gatherers, the price of food was the hard work it took to hunt and forage. This drove many species to extinction, and led to food shortages. The cheaper substitute was for the farming of grains to become the main source of sustenance.

Interestingly, the real price of copper has again ascended throughout 2021 and 2022. Insofar as engineers are free to innovate, we may again witness engineers devising still other replacements for copper in machinery.

Natural Fact Two (of Two): Greater Utility From Fewer and Smaller Inputs | ^

The economic value that a business produces for its customers is called “output.” “Inputs” refer to the resources that must be used up in the process of generating the output. Inputs include both human labor and the natural resources that the operation entails.

To the extent that people are free and their private property rights are enforced, every input in an entrepreneur’s operations imposes a cost upon that entrepreneur. Thus, the entrepreneur downsizes her costs, and thereby upsizes her profits, insofar as she employs new techniques for producing at least as much economic value as she did before from ever-smaller and ever-fewer inputs of labor and natural resources. And she can also cut costs by producing at least as much economic value from smaller and fewer inputs of tools and machinery. Those tools were created by still other entrepreneurs in prior efforts at coordinating the laborers’ interactions with the natural resources. Hence, everything ultimately comes down to getting more value out of smaller quantities of labor and natural resources.

Frustratingly, such considerations do little to deter those of a particular political ideology from intoning ominously that the size of the human population will outstrip the Earth’s bounty. These people dismiss, as naïve, the notion that firms can simply boost their profits by improving efficiency and reducing waste. Those people scoff because they grossly underestimate the extent to which, throughout history, such efficiency improvements and waste reductions have been a major source of growth in profits.

A case study of this is to be found in the evolution of electric dynamos. The power plant that Thomas Edison finished constructing in 1882 on Pearl Street in Menlo Park, New Jersey, had six Jumbo dynamos. Each of these dynamos weighed 54,000 pounds and generated 100,000 watts. That is 1.85 watts of electricity generated per pound of machinery. By contrast, a gasoline-powered 10,000-watt dynamo constructed by the firm Briggs and Stratton in 2020 generated 34.7 watts per pound.

Edison’s total investment in the Pearl Street power plant was $600,000. In 2020, U.S. dollars, that comes to $17.28 million. Hence, Edison generating 600,000 watts would cost him, in 2020 U.S. dollars, $28.80 per watt generated. In 2020, an entrepreneur could buy sixty Briggs and Stratton generators, each for $2,000. For that entrepreneur in 2020, generating a single watt of electricity would cost 20 cents.

Here we find that, due to efficiency improvements, a single pound’s worth of material comprising a dynamo in the year 2020 could generate more than eighteen times as many watts in electricity as Edison’s dynamos could, and at less than one percent of the cost.

And that is far from all. Consider the nonrenewable natural resource that is coal. Every few years during the early twentieth century, engineers introduced another model of coal-burning machinery that exerted greater thermal efficiency than did the older models. In the year 1900, more than seven pounds of coal had to be burned to power a 100-watt lightbulb for one hour. By the year 2000, for that same lightbulb to perform that same task required burning less than a single pound.

That principle can be expressed through other figures. Lumens are the units by which light is measured. In the year 1898, one watt powering an incandescent lightbulb would produce six lumens. In 1920, that watt produced ten lumens. In 2003, it would be 200 lumens.

That is less and less coal per lumen.

Recall the point from earlier about Edison’s dynamos. In 1898, a single pound’s worth of Edison’s dynamo would generate 11.16 lumens. By 2003, a single pound’s worth of a Briggs and Stratton dynamo could supply 6,940 lumens. In a little over a century, then, the number of lumens generated by that single pound of material had grown over 600-fold.

Indeed, steel has been used more efficiently over the course of the century. Over 68 percent of the steel put to work in the U.S. economy is recycled annually. When this alloy is newly produced and is being installed for the first time, it is called “virgin steel.” That is treated more economically as well. Steel still goes into automobiles, but not exactly in the same fashion as in previous decades. That is one reason why the weight of automobiles dropped by one fourth between the years 1970 and 2001. For such reasons, between the years 2000 and 2015, even as there was an increase in the quantity of products containing steel, total use of the alloy in the United States fell by 15 percent.

Virgin steel is set to work more efficiently than before and, in turn, it is produced more efficiently as well. Producing steel has always required that iron be heated to the extent that it takes on a molten form. At the opening of the nineteenth century, producers had to burn an average seven tons of coal to churn out a single ton of “blister” steel. This changed in 1856 with inventor-entrepreneur Henry Bessemer introducing the process named for him, wherein cold air would be blasted upon the super-heated iron. Then it took no more than 2.5 tons of coal, in super-heated “coke” form, to finalize a ton of higher-quality “crucible” steel. By the year 2020, putting out that same ton of steel required less than 0.86 tons of coal.

And coal is not the only resource being inputted more economically in steelmaking. Between the years 1930 and 1949, making a single ton of steel cost an average 200 tons of water. That figure decreased to 20 tons by the 1980s. By 2018, the most efficient plants could make a ton of steel from three to four tons.

Insofar as individuals are free to enterprise peaceably, several facts of Nature guard against the depletion of resources. The first fact is that many different types of resources can be applied for the same use. That means that as one resource used for a particular purpose grows scarcer in current availability, human beings can switch to an alternate resource to substitute it. For much of the nineteenth century, people harvested liquids from sperm whales to light their lanterns. It was as whales grew scarcer and their oil gained in price, that Abraham Gesner discerned that kerosene could be marketed as a cheaper substitute. And copper provides another example.

Yes, continue the enemies of capitalism, human being can use their engineering know-how to substitute a scarce resource with a more plentiful one. Still, they ask, how does economics reward entrepreneurs from guarding against the depletion of nonrenewable natural resources on the whole? The answer has to do with the entrepreneurs’ costs being a function of the quantity of natural resources they drain. Thus, we come to the second pertinent fact about preventing the depletion of resources. As humans gain a greater degree of scientific knowledge about their resources, they are indeed able to improve the efficiency of how these resources are expended. And this principle applies even when a more abundant resource cannot be acquired as a substitute for a scarcer one.

↑ Profit = Economic value to customers (Revenue from sale) – ↓ Cost of natural-resource inputs

That involves the development of technologies that improve efficiency.

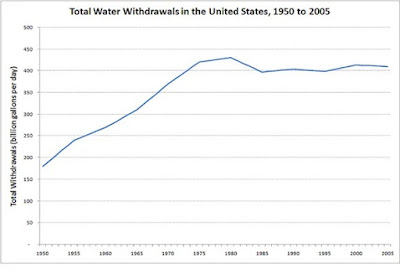

For most of the USA’s history, the total quantity of water used daily steadily increased. But that peaked around the year 1975 at 425 billion gallons per day. From then on, the quantity of water Americans washed down daily remained relatively stable, even as the population and industrial output both grew. From 1984 to 2004, the USA’s per-capita water usage actually dipped by twenty percent.

In the year 1975 in the United States, every cubic meter of water inputted for industrial purposes yielded, in 2021 U.S. dollars, an average eleven dollars in utility. By 1999, also in 2021 U.S. dollars, that figure doubled.

Gasoline is another nonrenewable input that the market conserves. The inventor and engineer Soichiro Honda, for whom the famous auto company is named, thought that motorists deserved more out of their driving experience. He assembled a team of engineers, including future Honda president Tadashi Kume, to put out a more economical car, the Honda Civic with its CVCC engine. In 1973, before the CVCC engine existed, a motorist could travel 12.9 miles on a single gallon of gasoline. Starting in 1975, upon release of the CVCC, that same gallon would take that same motorist six miles farther. In 2014, that same gallon would take a car farther than 21 miles.

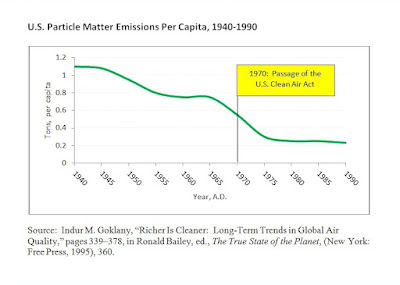

The automobile engines of 2002 were twice as powerful as were those from thirty years earlier. Yet they emitted half as much in exhaust fumes.

Other modes of transportation undergo the same evolution. Compared to one from 1970, a Boeing 747 commercial airliner in 2002 was half as loud and consumed 17 percent less fuel even as it worked at a quarter more horsepower at takeoff. In the duration of 1960 to 1990, the thrust-to-weight ratio in commercial jet engines increased from 4.2 to six. Similarly, between 1940 and 2000, the thrust-to-weight ratio of the gas turbines in these same airplanes lifted from 15 percent to more than 40 percent.

Pollutants that firms release into the air and water are waste byproducts — those are the part of the input that cannot be put into production. As firms gain in efficiency and put every part of the natural-resource input into production, that reduces the waste and therefore reduces the pollution. That is why in both the United States and United Kingdom, firms had been reducing their emissions of toxins in the air even prior to these countries each passing their own particularly strict Clean Air Act.

In the 1950s, a mainframe computer would take up the space of an entire room, sometimes even an entire building. In 2020 U.S. dollars, the cost of assembling and maintaining such a machine was in the millions. A single digital watch today priced at $35 exercises more computing power than did any of those mainframes. A pocket calculator from the year 2000 already computed 350 times faster than did the computers involved in the Apollo 11 mission. Inventor-engineer-entrepreneur Ray Kurzweil makes an even more impressive comparison. He says that in the 1970s, considering the state of technology at the time, it would have taken trillions of U.S. dollars’ worth of resources to build a computer with the same amount of computing power as those of the smartphones that African villagers were carrying around in 2013.

Speaking of mobile phones, from 1990 to 2011, the average weight of one shrank from twenty-one ounces to four ounces. That is, a mobile phone from 2011 was less than one-fifth the weight of one from two decades prior. Much of this trend has to do with the aforementioned improvements in efficiency of the lithium-ion batteries inside these mobile devices. Between 2008 and 2015, the quantity of kilowatt hours generated per liter of lithium-ion doubled from 200 to 400. And between 2010 and 2017, the quantity of watt hours per kilogram of lithium-ion almost tripled from a little over 100 to 300. Stated in other terms, a mobile phone manufactured in 2015 could perform the same tasks as one from 2008 on just half the amount of lithium.

Using the weight as a proxy in measuring mass, we can discern that a particular product today can produce the same output as that product’s counterpart from decades ago even though the product of today uses up a smaller quantity of mass from natural resources.

That is visible with someone we mentioned earlier, that of Jonathan Rothberg and his portable and wheeled MRI machine, the Hyperfine Swoop. Compared to a standard MRI scanner from 1977, Rothberg’s Swoop is ten times lighter in weight and consumes 35 times less energy.

This likewise happens with household tools. The first power drills came out in Germany in 1895. Each weighed seventeen pounds and was only slightly more powerful than a hand-cranked drill. To operate it, someone had to grab its two handles and hold it up to one’s chest. The on-off switch was far away from the machine. To turn it off, the operator had to take his hand off the tool itself. That way, the operator could lose control of the machine and injure himself. In 1917, the American inventors Samuel Duncan Black and Alonzo G. Decker, Sr., introduced a variant that was eight pounds — less than half that of its predecessor — and was easier to use. It had a trigger like a gun that, when pulled, turned the drill on. They priced it at $230, which is over $5,000 in 2020 U.S. dollars.

By 1921, Arno H. Petersen made a version that was still more ergonomic. Instead of putting the trigger where it would go on a gun, Petersen put it on a handle behind the motor. This put less stress on the forearm of the person operating it. And it was four pounds, and sold each unit at $42. That is $609.32 in 2020 U.S. dollars. Petersen’s version, christened the “Hole Shooter,” serves as the general model for those being manufactured in 2022, being roughly the same weight and largely the same in design. In short, the power drills at the time of this writing generate the same output as those from 1895 but are less than a quarter of their weight and sell for less than one percent of their real price.

In 2001, science journalist Ronald Bailey provided other examples of consumers receiving the same or greater economic value from products that consisted of less mass, overall, than did their counterparts from prior decades. That year, food cans were half the weight that they were in 1951. Likewise, plastic soda bottles were only seventy percent the weight of those being sold in the 1970s, and the ones from the 1970s were already lighter than the glass bottles they replaced.

We can dispel any notion that the reduction in the quantity of one category of natural-resource inputs in every unit produced simply shifts to an increased used of a different natural-resource input for that unit. We can do so by examining how much energy altogether is expended on creating an average unit of economic value. This can be done by looking at overall energy intensity. This is how much energy in total — coal, oil, nuclear, and renewables combined — go into the production of economic value. Energy intensity measures the quantity of megajoules that had to be generated to produce an average inflation-adjusted dollar’s worth of economic value. A reduction in the energy-intensity ratio over time means that smaller and smaller quantities of natural resources must be converted into energy to generate the same amount of economic value.

And that is what we find. From 1880 to 2000, the number of megajoules that had to be generated in the USA to bring forth a constant 1990 U.S. dollar’s worth of economic value shrank from 50 to 15. For the United Kingdom in the year 1830, 35 megajoules had to be generated to produce a constant 1990 U.S. dollar’s worth of value. By the year 2000, it was 15.

It may be said that even if a specific unit of a good has shrunk in mass, such as computers getting smaller, the total quantity of natural resources consumed annually has expanded on account of the number of units produced growing annually as well. But, no, the improvements in efficiency have even preempted a major increase in the total quantity of natural resources consumed per year.

Economists calculate the weight of all the goods and services circulating through the U.S. economy. Once again, we use the weight of objects as a proxy in measuring their mass. Alan Greenspan notes that since 1977, the estimated real goods output of the United States annually has maintained a relatively stable weight.

It reached high points of 1.2 billion metric tons in the separate years of 1979 and 2013.

Rockefeller University scholar Jesse Ausubel writes that among 100 commodities studied by Paul Waggoner, Iddo Wernick, and himself, the total annual usage of 36 of them —including steel, timber, paper, asbestos, and chromium — peaked in 1970 and then dropped off since then.

All this happened even as the American economy experienced a net growth since 1979. The increase in wealth is due not to the natural resources themselves as much as how smartly those natural resources are being utilized.

The Carrying Capacity of Land | ^

“That may be all well and nice,” one reply may go, “but there is still an important commodity of which you cannot produce any more units, no matter how cost-effective are. There really is a fixed quantity of land. Its carrying capacity —the number of people who can safely fit on it and live — is finite.” Yet market economics have indeed increased the carrying capacity of that. Technological improvements have allowed for a larger number of people to live peaceably on the same square acreage as before. Secondly, the same plot of land can grow greater quantities of food than it has in centuries past.

For much of the past several thousand years, human beings had difficulty with high-rises. Most buildings were structures supported by their outer walls. The taller the structure was, the greater a burden the structure put on its base. The base had to be the widest section, much wider than the building’s top. Hence, most tall artifices, be they in Egypt or in Mesoamerica, had to be constructed in the shape of pyramids. The walls having to be wide reduced the space on the interior, and there was less interior space still near the top of the structure.

This was dealt with in the late nineteenth century. As the population increased in size, so did the real price in housing. Would-be entrepreneurs knew they could profit if they could devise an economical method for fitting more people comfortably on the same quantity of land.

One day upon looking at his wife’s bird cage and the bars on the outside, inspiration breathed new life into architect William LeBaron Jenney. Limitations were placed on a building’s height exactly because of how architects had traditionally relied on the outer walls supporting the structure. Instead, Jenney reasoned, the structure should be supported by a metal frame — a sort of skeleton — inside the inner walls. The construct, then, would not need to be pyramid-shaped; the highest story could be just as spacious as the lowest.

This greatly increased the carrying capacity of land. As noted by London’s Economic Development Office, “Accommodating the same number of people in a tall building of 50 stories as in a large building of five stories requires roughly one tenth of the land.”

Many great technologies enabled farmers to grow more food per acre of earth. From 1950 to 2001, corn yields per acre in the United States tripled.

Improved Productivity Helps People on the Lower Income Distribution | ^

Citing a 2004 study by Erik Rauch at MIT, utilizing U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data from 1947 to 2000, Silicon Valley tech writer Andy Kessler observes that by the year 2000, someone would only need to work eleven hours a week to attain the equivalent value of what someone earned from a full forty-hour work week in 1950. To put it into perspective, Kessler writes that “we could have knocked 30 minutes off the average work week every year since 1950” and by the year 2000, “still maintained our 1950 standard of living.”

And, indeed, even as lithium is employed more efficiently in machines, its real price keeps falling. Between 2010 and 2019, its price per kilowatt hour in 2021 U.S. dollars descended from $1,253 to $166. In nine years, that was a more-than-fivefold decrease.

Examining females in the Hiwi band who reach the age of fifteen, only a quarter will live to 70. By contrast, with fifteen-year-olds in a modern industrial society, three quarters can expect to be around for their seventieth birthday. In members of the Arikara clan found in mass burial sites, the mortality rate for those aged 20 to 40 was 15.3 percent. In American citizens today in that same age range, we find a mortality rate of 3.7 percent.

Ah, counter the opponents of commercialism, escaping the evils of capitalism does not require that we go so far as abandon modern technology in favor of a return to being hunter-gatherers. Nay, they say. We can adopt the political-economic collectivism that is common to hunter-gatherer bands while maintaining the conveniences brought about through industrialization. This shall be accomplished, they offer, through old-fashioned socialism of one sort or another.

Ever since the rise in popularity of Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, it has, once again, become trendy for Americans to insist that socialism could provide this wealth to a much greater degree than capitalism. The history of the twentieth century does not bear out such an assertion. To the extent that capitalism’s detractors think of socialism as the rich being taxed to pay for social service programs for the poor and middle class, that is actually a welfare state or regulatory-entitlement state. There are great weaknesses to this alternative, but that is another essay for another time.

Let us compare “socialism” as it has been more traditionally defined from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. “Socialism” here refers to the public —usually with the government acting as its representative — having collective ownership over heavy industry, such as steel production and automobile manufacture. When a national government has its own agency attempt steel production or auto-making, that agency is known as a State-owned enterprise (SOE). Rather than the selfishness imputed to competing firms that seek profit, the State-owned enterprise is nonprofit and supposedly acts for the good of all.

If we want to look at such socialism being practiced in countries that remained democracies, we can look to Sweden, the United Kingdom, and France from the end of World War II to the late 1970s, the latter period being when the government began converting the SOEs into privately owned, for-profit firms.

Ove Granstrand and Sverker Alänge partook in a study of their native Sweden, examining the origins of the country’s hundred “most economically important innovations” to emerge in the duration of 1945 to 1980. Eighty percent of the innovations originated from major private, for-profit corporations. Twenty percent arrived from then-small startup firms. By contrast, innovation from State-owned enterprises was “marginal,” . . . meaning zero.

It reached high points of 1.2 billion metric tons in the separate years of 1979 and 2013.

“That may be all well and nice,” one reply may go, “but there is still an important commodity of which you cannot produce any more units, no matter how cost-effective are. There really is a fixed quantity of land. Its carrying capacity —the number of people who can safely fit on it and live — is finite.” Yet market economics have indeed increased the carrying capacity of that. Technological improvements have allowed for a larger number of people to live peaceably on the same square acreage as before. Secondly, the same plot of land can grow greater quantities of food than it has in centuries past.

One day upon looking at his wife’s bird cage and the bars on the outside, inspiration breathed new life into architect William LeBaron Jenney. Limitations were placed on a building’s height exactly because of how architects had traditionally relied on the outer walls supporting the structure. Instead, Jenney reasoned, the structure should be supported by a metal frame — a sort of skeleton — inside the inner walls. The construct, then, would not need to be pyramid-shaped; the highest story could be just as spacious as the lowest.

And the result of all the aforementioned entrepreneurial ingenuity has been improved living standards. Moreover, with the exception of one category of product we will discuss later, this has led a reduction in real prices over most consumer goods, especially food.

Here we must emphasize the distinction between nominal prices and real prices. Nominal prices are the price of a product taken at face value. A candy bar priced at two cents in 1904 was 44 cents in 2009. The nominal price in the latter year was twenty-two times that of the former year.

The main cause of inflation is the U.S. Treasury and U.S. Federal Reserve putting more and more monetary units in circulation. When the quantity of monetary units increases at a rate that exceeds that rate at which the quantity of goods and services increases, that is more monetary units chasing after the same goods and services. Vendors have to raise the nominal prices of their goods; otherwise, there will be a shortage. This inflation hurts most the parties that are living on savings and fixed incomes, such as senior citizens collecting their retirement. That is why policymakers should listen to free-market advocates concerned about the Treasury and the Fed devaluing the currency. But that is another essay for another time.

Germane to this particular essay, because inflation obscures actual changes in prices, we need another metric by which to judge the extent to which prices have changed over the decades. Many economists rely on something called the “consumer price index” in order to measure inflation. With it, they calculate how much economic value a U.S. dollar from today could have purchased in past years, be they 1930, 1940, or 1950, and vice versa. What a single nominal U.S. dollar could purchase in 1900, for example, was the equivalent of what a nominal $31.10 could purchase in 2020. A price that is calculated to account for inflation is known as “real price.”

Economist W. Michael Cox, formerly of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, has another approach. He asks his fellow citizens to consider the average amount of time someone had to spend at work in order to purchase a particular good.

By that standard, the trend has been for important goods to get cheaper and cheaper. For someone in the year 1930 to afford 100 miles’ worth of air travel, that person would have to do the equivalent of twelve hours and 46 minutes’ worth of work. By 1990, one could purchase that same 100 miles of air travel by working one hour and two minutes. In 1900, affording 100 kilowatt hours of electricity would entail working for 107 hours and 17 minutes. By 1990, that quantity could be earned by spending 43 minutes at work.

The same trend is seen with food. In 1940, a person had to spend one hundred hours on the job to be able to purchase a three-pound chicken. By 1990, that chicken could be purchased after spending fewer than twenty minutes. The downward trend in prices here cannot be attributed properly to federal legislation such as the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. The price of chicken was already falling. Between 1900 and 1930, the number of hours one had to labor to obtain this three-pound chicken fell from 160 to 110.

For many consumer goods today, a single hour of work will buy for someone in the First World a larger quantity of these consumer goods than that same hour of work would have fetched for any previous generation. That is a net gain in wealth for everyone in the First World.

In the United States, a household falling under a certain income threshold puts it under the official federal poverty line. Whether the household is in poverty is calculated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services according to the household’s income and the number of people living in it. As of this writing, a family of four is under the poverty line if it brings in less than $26,500 annually. Even many households under this poverty line provide evidence of how living standards improve to the extent that people are free. In 1950, fewer than 80 percent of all U.S. households possessed a refrigerator. By 1997, a refrigerator was in 90 percent of U.S. households falling under the federal poverty line.

Goods That Have Not Decreased in Real Price | ^

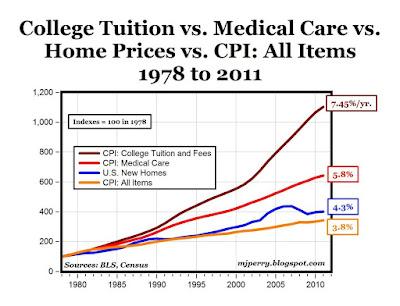

The general trend for units of consumer goods is not only for smaller quantities of natural resources to be inputted into their creation but also for them to decrease both in real cost for the manufacturers and real price for consumers. All these reductions are the consequence of improved industrial efficiency. Yet one may notice that the general price decreases do not apply to most of the pharmaceuticals and medical devices I mentioned in Part One of this essay. That is because, sadly, there is one large, general category of product to which the reductions in real price have not applied. This is actually not a failing of laissez-faire free market principles, however.

The products that have not decreased, but which instead have often increased, in real price include health care, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, higher education, and residential homes. What these goods and services have in common is how much of a financial commitment they all are. And they have something else in common. It is that the federal government has instituted measures to help people obtain cash or credit to procure these goods and services. Medicare and Medicaid assist in paying for health care, prescription drugs, and medical devices. Federal loans assist in obtaining higher education and housing — two goods so great in expense that they are paid for in installments.

These are taxpayer subsidies. Even if the borrower pays back the federal loan’s principal plus interest, there remains, on a net balance, a taxpayer-funded payment to the borrower. The reason for that is that the interest rate the federal government charges is always less than the interest rate that would have been charged by a privately owned lending institution. The difference between the government’s and the private lenders’ interest rates is absorbed by taxpayers.

What happens is as follows. First, a particular good in this category is considered too costly. The government then provides taxpayer subsidies to assist in purchasing these goods. However, this raises demand, and the providers of these goods respond to this rise in demand by raising prices. Paying for real estate grows more daunting, as it does with university tuition. As these prices ascend, activists and the general public clamor for larger subsidies to cover these new higher prices. Taxpayer subsidies purported to make a particular good more affordable therefore ultimately make that good more expensive.

Although other writers such as economist Richard Vedder have described this phenomenon before he did, Robert W. Tracinski gives an apt name for this — the Paradox of Subsidies.

Laissez faire is not to be blamed for this predicament. Nor does it follow that these goods and services would not decrease in real price if none of the taxpayer subsidies existed. Cosmetic surgery and LASIK eye surgery, for example, are not covered by health insurance or taxpayer subsidies. Exactly for that reason, such procedures have plunged in real price over the past 15 years.

Recall that throughout the 1950s, Percy Julian was able to reduce the price of progesterone tenfold. By contrast, the legislation in 2006 to ensure that Medicare pay for prescription drugs has only driven up the real price of medication.

Laissez faire not being the culprit for the rising real price of taxpayer-subsidized goods, we see that in areas where markets are freer, the freedom of enterprise to improve efficiency has shrunk the quantity of natural-resource inputs used and has lowered real prices for goods and services.

The Poor Get Richer | ^

Yet most of the world’s human population persists in being poorer than it should be. As discussed earlier, there are still many casualties from people breathing — as they try to keep warm — the fumes rising from their fireplaces. The main reason for the holdup in development is that most countries have kleptocratic governments. People practice commerce but their governments usually refrain from protecting them from theft. Often on a whim, the State itself will seize the people’s meager belongings. But as to the extent that they have experienced any liberalization, such as the country becoming more open to international trade and direct investment, the perks of liberalization have conferred improvements in living standards upon the developing world’s residents.

Consequently, average living standards have climbed in both the rich countries and the developing ones over the past half-century. It is here often interjected that the statistical mean, the average among all the numerical figures, is not always the statistical mode —the numerical figure that, among all the cases, recurs most often. If the mean global annual income shot up, what if all the gains went to the wealthiest one percent of the population? Maybe inflation-adjusted incomes for everyone else has remained the same or fallen? The economists David Dollar and Aart Kraay looked into this. They found, “When average income rises, the average incomes of the poorest fifth of society rise proportionately.” A trio of academic economists led by John Luke Gallup had a corroboratory result. They discerned “a strong relationship between overall income growth and real growth of the income of the poor.”

We can gain insight into these changes by observing what the United Nations defines as life-threatening absolute poverty. Someone falls under that threshold if that person makes less than $1.90 per day in inflation-adjusted 2019 U.S. dollars. This should not be confused with the U.S. federal government’s criterion for falling under the country’s official poverty line. Someone can be under the U.S. poverty line but still be out of absolute poverty by the U.N.’s standard.

Overall, the rate of life-threatening absolute poverty has been slashed, even in the developing countries. Between 1981 and 2008, the share of the global human population in life-threatening poverty dropped from 52 percent to 22 percent. That is a figure sliced by more than half.

And China’s ascension to wealth is not sufficient to explain this decline. Professor Max Roser of Our World in Data scrutinized what the results were when China was excluded. In 1981, 29 percent of the non-Chinese human population was in absolute poverty, whereas in 2013 the figure was 12 percent. For such reasons, Georgetown University economics professor Steven Radelet finds it necessary to emphasize that the “improvements” in living standards among the developing countries “go well beyond China.”

Many find it tempting to attribute this poverty reduction to taxpayer-funded foreign aid and to charitable NGOs. They have played a role, but a lesser one. Columbia University’s Howard Steven Friedman inquired into how much, between the years 2000 and 2013, the taxpayer-funded U.N. Millennium Development Goals (MDG) had to do with the developing countries’ gains in living standards.

It turns out the MDG had very little to do with the improvements; it was mostly for-profit commerce and private charity. In the few cases where some taxpayer-funded government project helped, such as with the construction of municipal roads, that came from municipal government and municipal taxation, not taxpayer-funded aid from the rich countries.

The World Bank does not attribute trade as the prime reason for the poverty reduction, but the trade does contribute to what the World Bank determines is the prime reason. As the World Bank explains, “the creation of millions of new, more productive jobs, mostly in Asia, but also in other parts of the developing world, has been the main driving force” behind the fact that “poverty has declined in the developing countries.” After all, “the private sector is the main engine of job creation and the source of almost 9 of every 10 jobs in the world.”

Among those jobs are those that capitalism’s detractors have reviled as exploitation. These would be initially low-paying jobs in factories established through foreign direct investment, factories often derided as “sweatshops.” From the 1950s onward, Asians opted for these sweatshops in the city because they paid two to three times as much as those in the village or country. Contrary to modern assumptions, in countries that are more politically liberalized we find that the trend is not for the majority of the workforce to be stuck in low-paying drudgery for decades on end. Reason magazine has profiled a factory in Taiwan that, during the 1970s, manufactured Barbie dolls. The workers in such factories saved their money and sent their children to schools to hone other skills. That is how countries such as Japan and Taiwan arose from destitution to First-World affluence. A similar phenomenon took off in India in the early 1990s with its deregulation of information technology.

The World Bank’s 2013 findings on poverty reduction corroborate Ayn Rand’s observations from over three decades earlier. She already noted that insofar as it has been implemented, capitalism has “raised the standard of living of its poorest citizens to heights no collectivist system has ever begun to equal, and no tribal gang can conceive of.” For such reasons, Rand related elsewhere, “If capitalism had never existed, any honest humanitarian should have been struggling to invent it.”

We often hear that capitalism must be fought by antipoverty programs. Yet capitalism is the antipoverty program.

That cliché that Percy Bysshe Shelley popularized about the rich causing the poor to become poorer is economically illiterate. To the extent that people are free to enterprise, the rich get richer and the poor get richer.

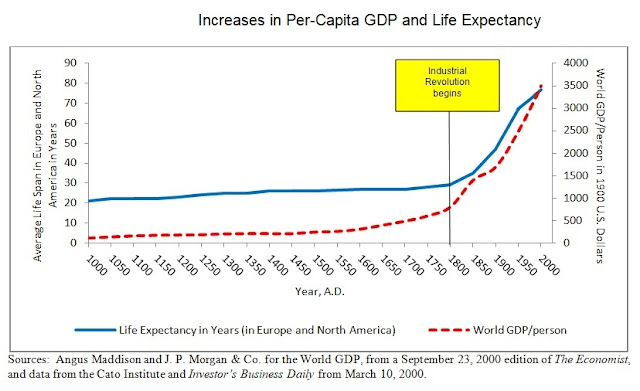

From the relative liberalization in the nineteenth century, and as a result of its consequent Industrial Revolution, the average lifespan in the United Kingdom, Western Europe, and North America ascended from 27 years in 1800 to 77 years by 1988. Starting in the late twentieth century, the developing countries began to experience comparable effects to the extent that they have been exposed to the gains of liberalization.

Georgetown University economist Steven Radelet points out that between 1980 and 2015, “the rate of child death has declined in every single developing country in the world where data are available. There are no exceptions” (emphasis Radelet’s).

And, as Max Roser notes at Our World in Data, the boost in average lifespan is due not only to reductions in the infant mortality rate. Thus, contrary to the final chapter of the book ScienceHeroes.Com was created to advertise, there is no conflict between “Our Health” and “Our Wealth.” Each of those reinforces the other.

Throughout Part One, we learned of how illustrious entrepreneurs organized the creation and distribution of specific products that saved lives. Here, in Part Two, we begin to see how all those efforts add up.

What Capitalism Can Do for the Climate | ^

For the purpose of saving space, I have relocated this section of the essay to this separate blog post. The bottom of that blog post has a link to return to this one.

Capitalism Vs. Hunter-Gatherer Life Vs. Socialism | ^

No, insist detractors. In lieu of just developing new technologies to continue with man’s consumption of resources, they declare, everyone should just learn to live on less —especially the vendors of the world. Anti-capitalists see vendors such as Wilson Greatbatch not as wizards who enrich others through their inventiveness as much as they see them as predators who extract money from customers.

These anti-capitalists remember a time in their childhoods when their parents or guardians provided the amenities. As adults, these anti-capitalists yearn for the presence of some still-higher-ranking parental figure who can bail out adults in their desperate hours. They remember stories of how human beings once had the abundance of the Garden of Eden, only to lose it. Upon being banished from paradise, human beings were thereafter doomed to mortality and the need to struggle for sustenance. No matter the net increases in global economic value provided by the George Westinghouses and Wilson Greatbatches of the world, they will never measure up to the standard set by Eden.

But the reality is reverse. The abundance of the Garden of Eden was never the default. Rather, the default has always been life-threatening poverty. Industrialization and capitalism “did not create poverty,” Ayn Rand elucidates. They “inherited it.” More than that, as we have seen, it is industrialization and capitalism that have done the most to alleviate this penury.

Socialism has over a century of promising that Edenic plenty, of all customers getting everything they need. And socialism has failed for that more-than-a-century, performing worse than whatever amount of capitalism has existed. Yet in its constant false promises, socialism continues to be hailed as more desirable than capitalism.

Such considerations are denied by various opponents of capitalism. Propagandist Michael Perelman huffs about private ownership of agricultural land replacing the practice of shepherds grazing their flocks on the medieval commons. Others go back even farther in time. They cite the living conditions of hunter-gatherers as far better. They cite figure about the average lifespan being low among hunter-gatherers is misleading. What mainly drives down the average life expectancy, goes the argument, is the high infant mortality rate. But, continues the argument, if someone lived to be two years old, there was as a great chance of her living to be eighty years old.

In the United States, a household falling under a certain income threshold puts it under the official federal poverty line. Whether the household is in poverty is calculated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services according to the household’s income and the number of people living in it. As of this writing, a family of four is under the poverty line if it brings in less than $26,500 annually. Even many households under this poverty line provide evidence of how living standards improve to the extent that people are free. In 1950, fewer than 80 percent of all U.S. households possessed a refrigerator. By 1997, a refrigerator was in 90 percent of U.S. households falling under the federal poverty line.

The general trend for units of consumer goods is not only for smaller quantities of natural resources to be inputted into their creation but also for them to decrease both in real cost for the manufacturers and real price for consumers. All these reductions are the consequence of improved industrial efficiency. Yet one may notice that the general price decreases do not apply to most of the pharmaceuticals and medical devices I mentioned in Part One of this essay. That is because, sadly, there is one large, general category of product to which the reductions in real price have not applied. This is actually not a failing of laissez-faire free market principles, however.

Yet most of the world’s human population persists in being poorer than it should be. As discussed earlier, there are still many casualties from people breathing — as they try to keep warm — the fumes rising from their fireplaces. The main reason for the holdup in development is that most countries have kleptocratic governments. People practice commerce but their governments usually refrain from protecting them from theft. Often on a whim, the State itself will seize the people’s meager belongings. But as to the extent that they have experienced any liberalization, such as the country becoming more open to international trade and direct investment, the perks of liberalization have conferred improvements in living standards upon the developing world’s residents.

For the purpose of saving space, I have relocated this section of the essay to this separate blog post. The bottom of that blog post has a link to return to this one.

No, insist detractors. In lieu of just developing new technologies to continue with man’s consumption of resources, they declare, everyone should just learn to live on less —especially the vendors of the world. Anti-capitalists see vendors such as Wilson Greatbatch not as wizards who enrich others through their inventiveness as much as they see them as predators who extract money from customers.

.

Westinghouse and other vendors, then, are not geniuses who have raised us beyond the living standards of cavemen. Instead, in expecting payment for units of their inventions, the Westinghouses and Greatbatches are holding these units for ransom. The customers’ need is the basis of what they deserve. Once the ransom is paid off, these vendors release to their customers the units of value that were rightfully owed to the customers from the outset.

There is something perverse about people citing, as a counterpoint to the idea that hunter-gatherer subsistence is harsher than modernity, the argument that it is only because of a very large infant mortality rate among them that the average life expectancy of hunter-gatherers is driven down so low. After all, as stated previously, the infant mortality rate among hunter-gatherers is usually one in four. People who make this argument should bother to listen to themselves. That the infant mortality rate would be large enough to do that should be acknowledged, from the outset, as a major indication of how much more perilous the conditions of hunter-gatherer life are. More relevantly, that it has been able to reduce the infant mortality rate from 25 percent to less than one percent is a credit to industrialization and modernization. This is the same industrialization and modernization being belittled.

Moreover, it is not accurate that as long as someone survived being age two, it made it likely for that person to reach age eighty. Overall, the mortality rate is lower for people in modern, liberal, republican, commercial societies than in hunter-gatherer bands, and for every age bracket.

CONCLUSION | ^

Accounting for everything, it is hardly doing justice to capitalism for Lindsay Ellis to say that corporations “make us stuff — not useful stuff, but stuff.” The “stuff” is more than useful. It includes pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and other goods that have lengthened lives and added to their quality and comfort.

Contrary to the assumptions of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and her counsel Dan Riffle, someone such as Patrick Soon-Shiong acquiring a billion dollars’ worth of monetary exchange value does not deprive the rest of the human population of a total billion dollars’ worth of resources. That entrepreneur’s billion is the consequence of that entrepreneur obtaining natural resources and, by exercising a technique to boost efficiency, changing those natural resources in such a manner that they now provide a greater benefit to human beings than they did in their previous state. The billionaire’s profit is equal to the new value that the billionaire’s efforts produced from the resources inputted, a net increase in the value of the resources employed.

Consider a gram of lithium. Starting in the middle of the nineteenth century, it was occasionally imbibed as a form of medication. For the most part, though, it was exotic. It would not have provided much value to the average person living in the year 1870 or even 1930. Once converted into a particular form, however, that same gram of lithium proved to be of much more practical and immediate value to someone in the year 2009. This is on account of electronics tycoons such as Craig McCaw, Philippe Kahn, and Steve Jobs having lithium power their mobile phones and of medical-device innovators such as Wilson Greatbatch exploiting it to enhance his pacemakers. That usefulness — that value — added to the lithium is economic value that such entrepreneurs created, and for which they are paid in kind. Absent of “the creative power of man’s intelligence,” Ayn Rand reminds us, “raw materials remain just so many useless raw materials.”

Hence, we understand the fallacy of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proclaiming, “I do think a system that allows billionaires to exist — when there are parts of Alabama where people are still getting ringworm because they don’t have access to public health — is wrong.” There is no merit to the insinuation that someone having a billion dollars contributes to those Alabamans having ringworm. The best hope for those Alabamans is that an ambitious scientist-entrepreneur will brainstorm a procedure whereby she can profit from providing those Alabamans better medical treatment than what they have received previously.

`

When it comes to what he said about twenty-three types of deodorant proving how Americans’ priorities are misplaced, it is projection on Bernie Sanders’s part. There is no inherent inverse relationship between children being fed and their parents being able to choose different types of deodorant. Through the smart employment of resources, there can be more meals for kids even as a variety of deodorants and snazzy sneakers go to market.

If someone acquires a billion dollars through the sale of goods or services, it is because his planning and organizing skills had created, for the world, a net increase in economic value of such magnitude that his customers willingly paid him a total one billion dollars for it. And those customers made such deals because what that entrepreneur provided them was of greater value to them than the money they paid him. The principle remains the same if an entrepreneur becomes a billionaire on account of a rise in the price of corporate shares he owns. In that case, the entrepreneur earns those would-be investors’ confidence that his company will profit its owners by providing great value to customers in the future. Anticipating that the entrepreneur will continue to exercise such competence, demand for ownership in the entrepreneur’s company increases among investors. The more eager the investors are to gain a piece of the action, the greater the demand is for shares in the entrepreneur’s company. Capitalism saves lives and is win-win.

Yet a reader who has been a longtime fan of Ayn Rand’s might notice that she was not fond of an expression like “capitalism saves lives.” That might initially seem strange, considering her status as capitalism’s biggest champion. But there is a special reason for this. The phrase “save a life” is usually spoken in a context where the default is someone going about her life only for some extenral threat to come at her suddenly, which is thankfully removed just as soon.

Capitalism, as Ayn Rand understood the term, is a social system where a liberal republican government allows for people to do anything that is peaceful. Trade and commerce in human history go back at least as far as the Neolithic Period. But even as this commerce was carried out, authority figures could arbitrarily overrule people’s trades and confiscate the fruit of their efforts. It was not until the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution that philosophers and statesmen began to enshrine, formally and eloquently, the individual’s right to live and prosper. There would always be some criminals who would try to prey on others, but they would be an aberration. In Ayn Rand’s estimate, then, capitalism did not keep having to “rescue” its citizens. Rather, as far as the threat of violence is concerned, capitalism allows for people to go about their lives without their having to be rescued or saved in the first place.

Definitely, modern industrial capitalism avails to people more opportunities than in centuries past, often because of the new resources whose creation industrial capitalism has facilitated. To try to make a career as a musician in antiquity or during the high Middle Ages, someone would usually have to be born into a family of musicians just to be able to access a high-quality musical instrument. Someone able to master such an instrument would usually then be confined to performing directly before a baron or a politically-connected family.

By contrast, as a consequence of the bounty that market-based industrialization has afforded, someone trying to be a musician today can access many more resources. A middle-class person can record her music and put it on the internet. If she can play multiple instruments, such as a bass guitar and the drums, she can record herself playing each instrument in a separate session, and then put all the sessions together as if she were an entire band playing all the instruments simultaneously. Achieving superstardom is still not easy. The process is more competitive than ever, but it is not for a lack of resources for someone of relatively modest means. Inasmuch as someone wants to pursue her own creative passions and dreams, no social system enables that more than constitutional, liberal republican capitalism. Capitalism enables you to live — not just in terms of survival, but to live in fulfillment, as in make an attempt at the sort of life you want for yourself.

The welfare state and socialism have promised to endow their citizens with greater material security than capitalism ever could; they promise greater access to healthcare and housing. Pursuing one’s artistic passions often interfere with the ability to work a more conventional job to pay for the amenities. Hence, our would-be musician may fantasize about receiving taxpayer funding that can secure her financially so that she has more time for her craft. But every resource a welfare state or socialist government hands out must be taken forcibly from someone. The contradiction inherent to socialism and the welfare state is that their promises of security to someone are enforced by the threat of police violence against others. Rather than say that capitalism saves lives, Ayn Rand judged that capitalism — insofar as it is implemented — is the only social system that enables someone to live a completely human life at all.

Hence, the closest Ayn Rand has come to saying that capitalism saves lives was in her observation that if capitalism itself needed to be “saved” — saved from being replaced by something else — or else the result would be peril to all. In her words,

Billionaires and capitalism do provide us “stuff,” yes, but there is a much grander result than that. To the extent that the relative freedom of a liberal republic has been of benefit to you, billionaires and capitalism have saved both your life and mine.

We must define, understand and accept individualism as a moral law, and Capitalism as its practical and proper expression. If we don’t — capitalism cannot be saved. If it is not saved — we’re finished, all of us, America and the world, every man, woman and child in it. Then nothing will be left but the cave and the club [emphasis hers].

Still, perhaps the principle can be phrased in terms that most people might find familiar. Capitalism does rescue people from the high mortality rates found in hunter-gatherer bands and other pre-industrial societies. If Ayn Rand had to write the phrase at all, it would probably be to state that capitalism saves your life every day.